Indrė Makaraitytė, LRT Investigation Team (LRT.lt)

Research OSINT: Alicja Pawłowska (FRONTSTORY.PL)

Visualizations: Anastasiia Morozova (FRONTSTORY.PL)

Illustration: Mariusz Kula 2025-05-01

Indrė Makaraitytė, LRT Investigation Team (LRT.lt)

Research OSINT: Alicja Pawłowska (FRONTSTORY.PL)

Visualizations: Anastasiia Morozova (FRONTSTORY.PL)

Illustration: Mariusz Kula 2025-05-01

- A group of Russian fraudsters created two pyramid schemes, called Recyclix and Juicy Fields, swindling victims out of €700 million.

- They rehearsed their scheme in Poland. At the height of their activity, they were featured in the media and even took photos with Polish president Andrzej Duda.

- After eight years of investigation, the Polish prosecutor’s office charged only a front man — and then let him go free.

- We later discovered that he became a GRU saboteur who sent out explosive devices that caused fires in Poland, Germany, and the UK.

- The first part of our investigation focuses on Recyclix. Click here to read the second part about the Juicy Fields pyramid scheme.

In April 2024, more than 400 police officers raided 38 locations across Europe and the Dominican Republic on the same day. The operation, codenamed “Operation Stoner,” was organized by Germany, Spain, and France, with support from Europol, and involved law enforcement officers from 11 different countries.

Most of those arrested held Eastern European passports. The most prominent among them, a Russian named Sergei Berezin, was arrested in the Dominican Republic. Viktor Bitner, a German citizen born in the USSR with ties to Russian intelligence services, was arrested in Germany. Another Russian accomplice, Nikolai Mikhailuk, was arrested in Lublin, Poland. The Polish police later published a video showing the confiscated equipment — laptops, memory sticks, and phones — as well as footage of Mikhailuk being led from the Lublin police station to a car.

Along with six others, they were suspected of organizing one of the largest scams in history: the Juicy Fields financial pyramid scheme.

Three months later, in July, a container of shipments caught fire at the airport in Leipzig, Germany — the blaze broke out just before the shipments were to be loaded onto a plane. The cause: one of the packages contained a concealed incendiary device.

According to Wyborcza, a day later, a similar shipment was activated in a truck near Warsaw. The next day, another device was found at a DHL facility in Birmingham, UK. A fourth device was intercepted by Poland’s Internal Security Agency (ABW). The packages had been sent by Lithuanian citizen Aleksandr Šuranovas, who was caught on CCTV wearing a T-shirt and shorts while mailing the bombs from a DHL office in Lithuania.

Aleksandr Šuranovas sends parcels containing explosives at a DHL branch in Vilnius. Photo: Wall Street Journal

The Lithuanian and Polish prosecutors claim that the parcels were sent on behalf of the Russian intelligence service GRU.

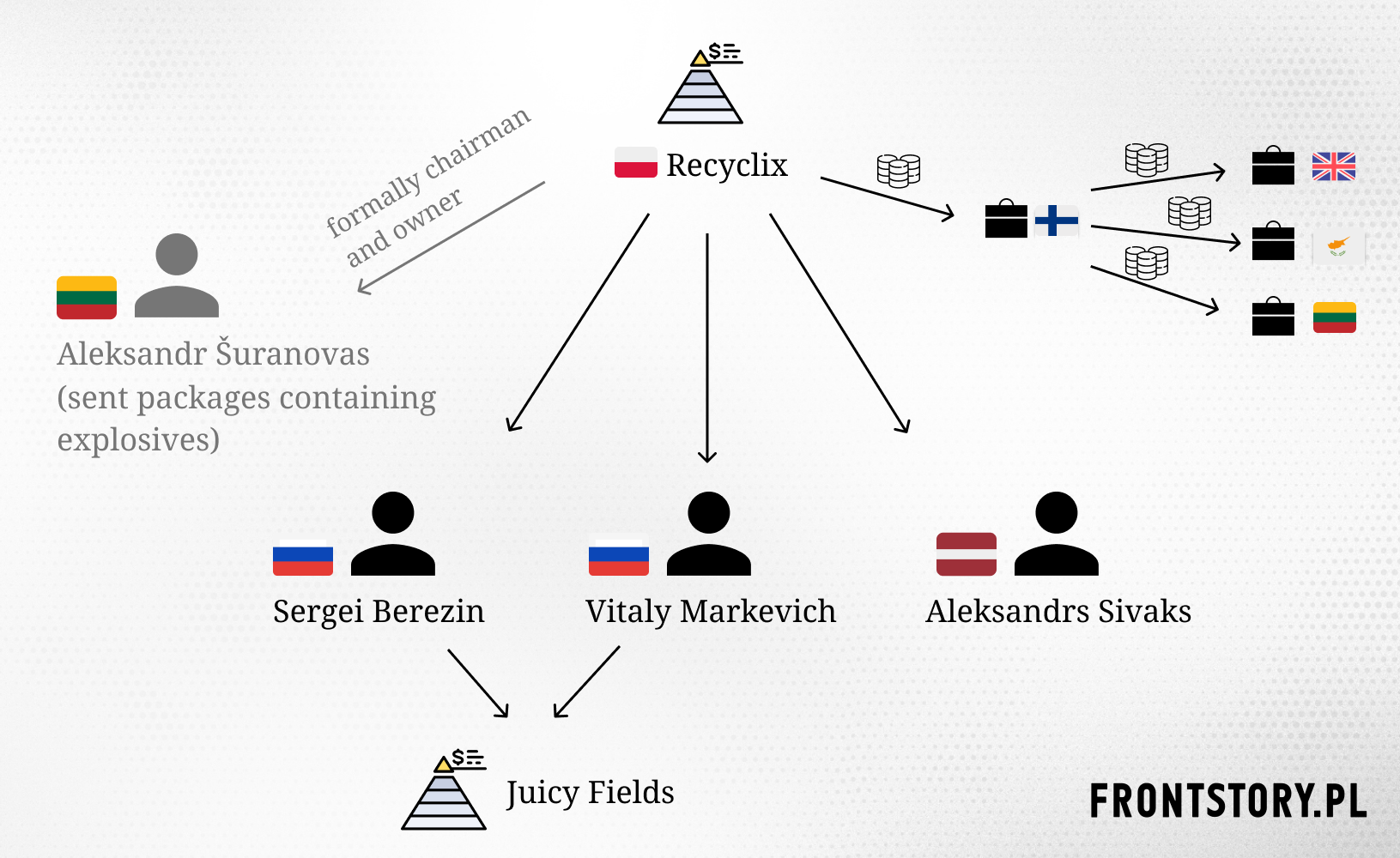

What connects the sender of the explosive parcels with the Russians from Juicy Fields? Šuranovas is their man. A decade ago, his associates set him up as the front man for the Polish company Recyclix, which received money from an identical scam. The swindlers defrauded customers of almost €40 million before disappearing.

What role does the Russian military intelligence service, the GRU, play in all this? Who are the people behind Recyclix and Juicy Fields? What connects them to Putin’s regime? How were they able to launch another pyramid scheme even though the Polish prosecutor’s office had them within reach? And how is it possible that money stolen from customers was used to build a military drone factory near St. Petersburg?

A Wagner Associate: Turning Against His Own

We have been tracking Šuranovas and his associates since October 2024. We established that the GRU saboteur and his colleagues from Russia quietly built and tested the Polish version of the Juicy Fields pyramid scheme. They named it Recyclix, after their Warsaw-based company. It was a trial run, a first attempt — and when things got hot, they disappeared with at least €39 million. Their next scam, Juicy Fields, was a pyramid scheme on steroids. This time, they stole almost €645 million from their victims.

The reality we uncovered behind the Recyclix and Juicy Fields gang is as dense and colorful as a thief’s ballad. The action unfolds quickly, across several continents, with exotic locations and colorful characters: expensive banquets on the French Riviera, celebrities, private jets, promises of easy profits, glitz, and luxury. Add to that fake aristocrats, medical marijuana, and — as the icing on the cake — a warm embrace with the president of Poland.

We will cover Juicy Fields in the next part of our investigation, but here’s a brief summary: in 2020, criminals from Russia (or with ties to Russia) created a platform that lured investors with promises of profits from medical marijuana cultivation. It promised sky-high returns to investors from around the world.

In reality, Juicy Fields never grew cannabis at all. The entire business, registered in Germany, Switzerland, Portugal, and the Netherlands, was a pyramid scheme — a scam in which investors’ profits were paid from the deposits of new users until the scheme’s creators shut down the operation and vanished to tropical islands.

The gang defrauded €645 million from 550,000 people, mainly Europeans. It stands as one of the largest Ponzi schemes in recent years.

After the pyramid collapsed and the criminals disappeared, investigators from Germany, France, and Spain took up the case. Igor Kekszin, a repentant gang member and former associate of the Wagner Group, revealed the real names of the leaders to both investigators and journalists.

It was Kekszin who disclosed that a few years earlier, the same group had created a nearly identical pyramid scheme in Poland, using a waste management business built around the Recyclix company to defraud investors.

Waste: Perhaps Worth Its Weight in Gold

In the spring of 2025, there is no trace of Recyclix; it has been removed from Polish registers.

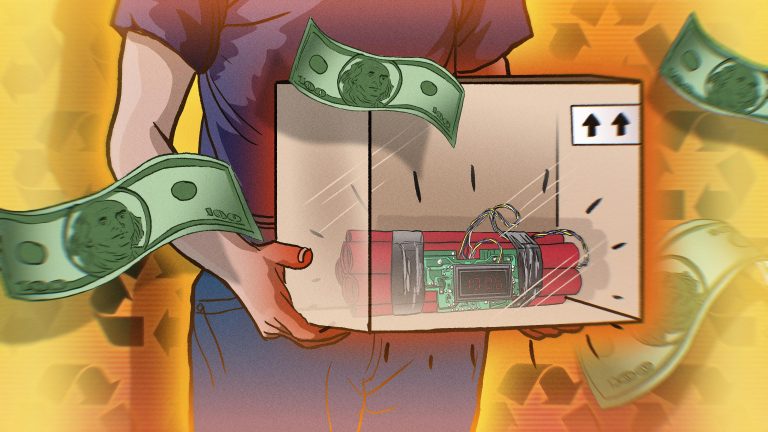

When it was founded a decade ago, the idea sounded enticing: the company would buy used plastic packaging, process it into valuable plastic granules, and resell it at a profit. Most importantly, the profits would be shared with investors through a crowdfunding model. The message was simple and appealing: even small savers could make a fortune from recycling — as long as they kept investing regularly and brought in new customers.

To share in the profits, investors had to deposit a minimum of €20 (with an incentive: each new investor received an additional €20 in virtual cash to use on the platform). There was also a commission bonus for deposits made by referred users.

The recycling profit game took place entirely online. On recyclix.com, with just a few clicks, you could buy several tons of plastic waste and then wait patiently for the company to process it into granules within five weeks. No need to worry about suppliers, sales, or efficiency — zero risk, pure income.

Where did the waste come from? Where was it processed into granules? Who were the buyers? Could you visit Recyclix factories — and if so, where? Customers didn’t ask questions.

Recyclix.com website

At first glance, the business — although legally registered in Poland — looked like a pyramid scheme. There were offers promising investors 14% annual returns, but even those typically involve risk. Recyclix, however, guaranteed its customers as much as 14% per month — 382% per year. Such profits are unimaginable even in the tech industry, let alone in the waste management sector.

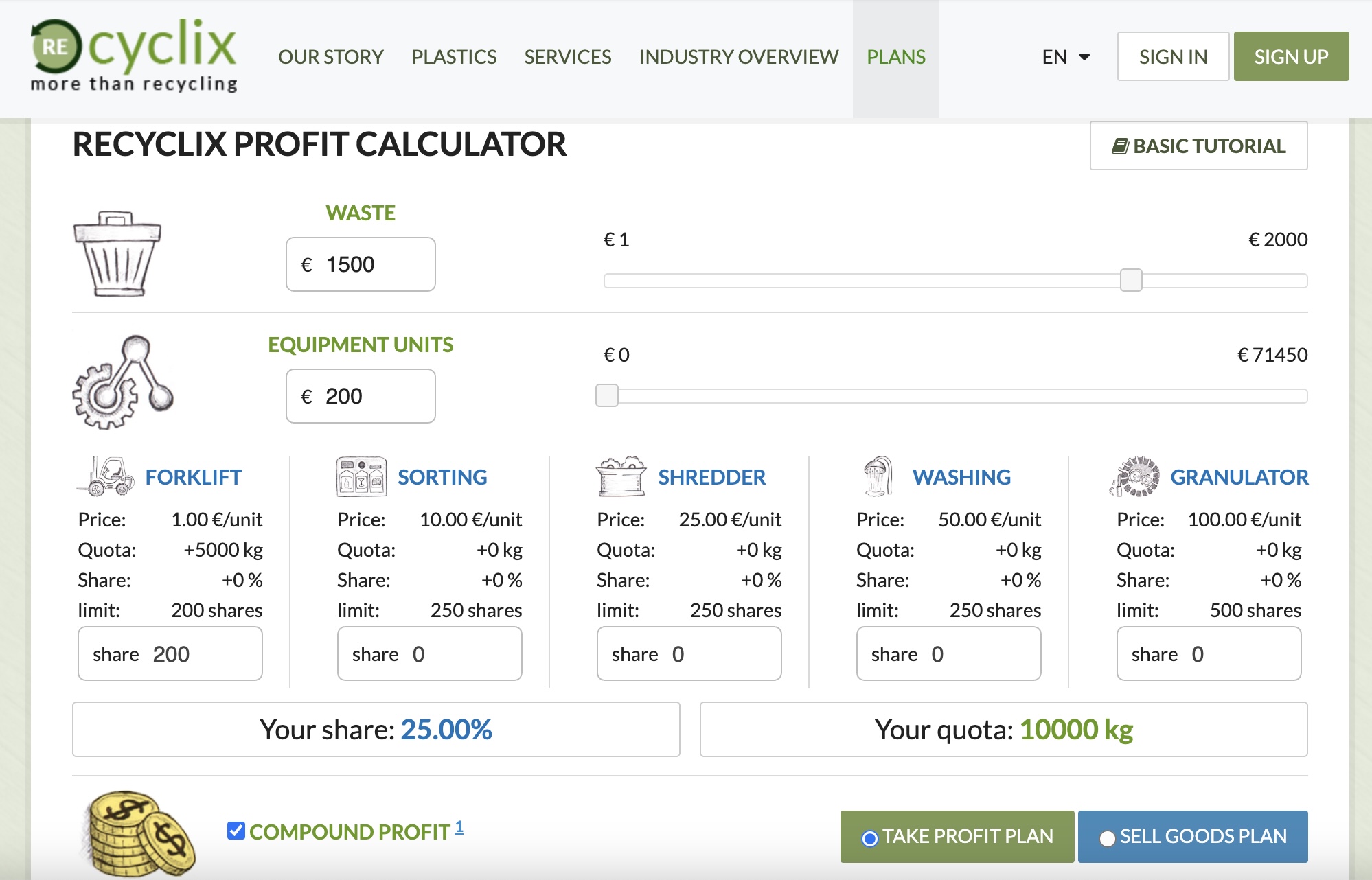

The hunt for victims began online in May 2015. To this day, you can still find posts from users back then who were enthusiastic about the platform. There are also screenshots showing payments in dollars or cryptocurrency — proof, in their eyes, that Recyclix was legitimate and truly worked.

The pyramid scheme was in full swing. Within a year and a half, it would vanish without a trace.

Recyclix customer post. Source: Facebook.com

CEO: Needs a Translator

Some users on forums and blogs were skeptical, suspecting it could be a scam. Why? Because:

-

You can’t make that much money from trash (the recycling industry was in crisis a decade ago);

-

If recycling were so profitable and its profitability expected to remain stable, why would Recyclix need crowdfunding? A regular loan would have been much cheaper;

-

In its terms and conditions, Recyclix explicitly stated that payouts to users came partly from other users’ deposits — a hallmark of pyramid schemes;

-

Suspiciously little was known about the company’s management.

The owner and CEO of Recyclix was Aleksandr Šuranovas, a 39-year-old Lithuanian citizen at the time — the same man who, a few years later, would be sending explosive packages via DHL. Yet his name did not appear anywhere on Recyclix’s website or in its promotional materials.

“I met Šuranovas once. He didn’t speak English, and I don’t speak Russian. I didn’t get the impression he was the boss — more like a puppet,” a former Recyclix employee (who wishes to remain anonymous) told FRONTSTORY.PL.

According to the company’s statements, the key management positions were held by Dimitrij Paladi, Mark Kowal, and Aleksandrs Sivaks. Their photos appeared in newsletters and conference reports posted on Facebook. However, only one of them — Sivaks — was using his real name. “Kowal” was actually Russian national Sergei Berezin, and “Paladi,” as we established, was another Russian — a businessman from St. Petersburg.

From left: Aleksandrs Sivaks, Sergei Berezin, “Dmitri Paladi.” Photo: Recyclix’s English Facebook page

We checked: the names of the three men do not appear in the company’s registration documents. Their social media accounts and professional histories are nowhere to be found online. Only Sivaks left some traces — he was the founder of a Latvian waste management company that had been inactive since 2010. He ran a one-man business in Latvia and even ran for local office. In Poland, besides Recyclix, he also founded Eco Revolution, another company supposedly focused on waste processing. As you might guess, it has not been operational for a long time.

We found a man strikingly similar to Sivaks in a photo taken during a 2016 demonstration in Riga marking the first anniversary of the murder of Boris Nemtsov, the Russian opposition figure shot dead in central Moscow.

Our artificial intelligence tools indicated a 99.9% match between Sivaks and the individual in the photo.

Demonstration in Riga on the anniversary of Boris Nemtsov’s death. First on the right: a man 99.9% similar to Aleksandrs Sivaks. Photo: parnasparty.ru

Africa: Believes in Recyclix

Skeptics on forums were met with fierce debate from believers: Recyclix couldn’t possibly be a scam, they insisted, because it had real factories and offices all over the world.

In August 2016, someone asked on the zarabiam.com forum whether Recyclix was a pyramid scheme. User Rafi213 replied: “Here we have a physical, tangible product that the company claims to be making money on (…), so there is a basis for believing them. However, nothing can be ruled out.”

Fact: Recyclix certainly operated on a global scale, with a website available in several languages. It boasted investors from Italy, France, and Austria. Its Polish office was located in Łomża, and foreign offices were listed in Latvia, Germany, Italy, Morocco, and Brazil. The company expanded into new markets mainly through Facebook, gaining followers in India, Latin America, and Asia.

On Facebook, Recyclix enticed users with reports from trade fairs and conferences in Riga, Brussels, Basel, Koblenz, and Abu Dhabi. In Ivory Coast, it was celebrated on the pan-African television channel Business24. Investors from the continent were enthusiastic. “Since I discovered Recyclix, I have been living off the profits, and I thank God because thanks to this, not only do I work very, very little, but I also have a lot of money,” said Pierre Onivogui, an entrepreneur from Conakry, the capital of Guinea, in front of the camera.

Duda: Supports and Sees Opportunities

Asia, Abu Dhabi, Basel, Łomża — and what about America? In 2017, the Brazilian press reported that Recyclix executives flew to the city of Ourinhos, near São Paulo, in two private jets. No one seemed surprised that, although the company had only been operating for a short time, its executives were flying around the world in their own planes.

Photos from the airport show the mayor of Ourinhos alongside a blond man in dark glasses and a flowery jacket — Mark Kowal (aka Russian national Sergei Berezin), the company’s chief operating officer. Next to him stands Aleksandrs Sivaks, Recyclix’s co-founder. They promised to build a factory in Ourinhos for 10 million reais (about PLN 13 million at the time) and to create new jobs.

Recyclix visits Brazil. From right: Aleksandrs Sivaks, Sergei Berezin. Photo: jpovo.com.br

Before the Recyclix empire reached South America, the waste purchased by investors from four continents was supposedly being processed by three factories: two in Latvia and a third somewhere in Poland — or perhaps two, as the number and locations of the factories often changed. “When I arrived for the job interview, Kowal and Paladi took me to a factory near Łomża. It wasn’t big, but it was real,” a former Recyclix employee told FRONTSTORY.PL.

Recyclix attracted investors with plans to build another factory in the economic zone in Łobez, near Drawsko Pomorskie. Sivaks promised to invest €20 million and employ 250 people. When Andrzej Duda visited the town in 2016, he praised the mayor for securing an investor who would provide jobs: “I encourage the mayor to create conditions for start-ups. (…) The challenge is to create such conditions in Poland — in municipalities, in counties, but also at the central government level — so that these opportunities exist. So that they exist many times over. And so that no one falls into debt because of a single attempt,” said the president in Łobez.

“Sivaks really wanted to meet him. The opportunity arose during Andrzej Duda’s visit to the city,” Piotr Ćwikła, the mayor of Łobez, told FRONTSTORY.PL.

A photo still circulates online showing Sivaks (officially Recyclix’s Latvian production manager) shaking hands with the Polish president.

No one questioned the fact that the factory in Łobez was not being organized by Recyclix but by Eco Revolution — another (bogus) company owned by Sivaks. Business was booming, and no one was asking difficult questions. Eco Revolution became a sponsor of the local newspaper, town celebrations in Łobez, and the football club. It even broadcast images from cameras installed at the factory construction site on its website.

Meeting between Aleksandrs Sivaks and Andrzej Duda in Łobez. Photo: Łobez Municipal Office

Meeting between Aleksandrs Sivaks and Andrzej Duda in Łobez. Photo: Łobez Municipal Office

Plastic Composition: It Just Burns

Two years passed between the company’s registration in Poland and the founders’ disappearance.

Just before the meeting with Duda, dark clouds were already gathering over Recyclix. In Italy, the Financial Supervision Authority had begun investigating the company for running a pyramid scheme.

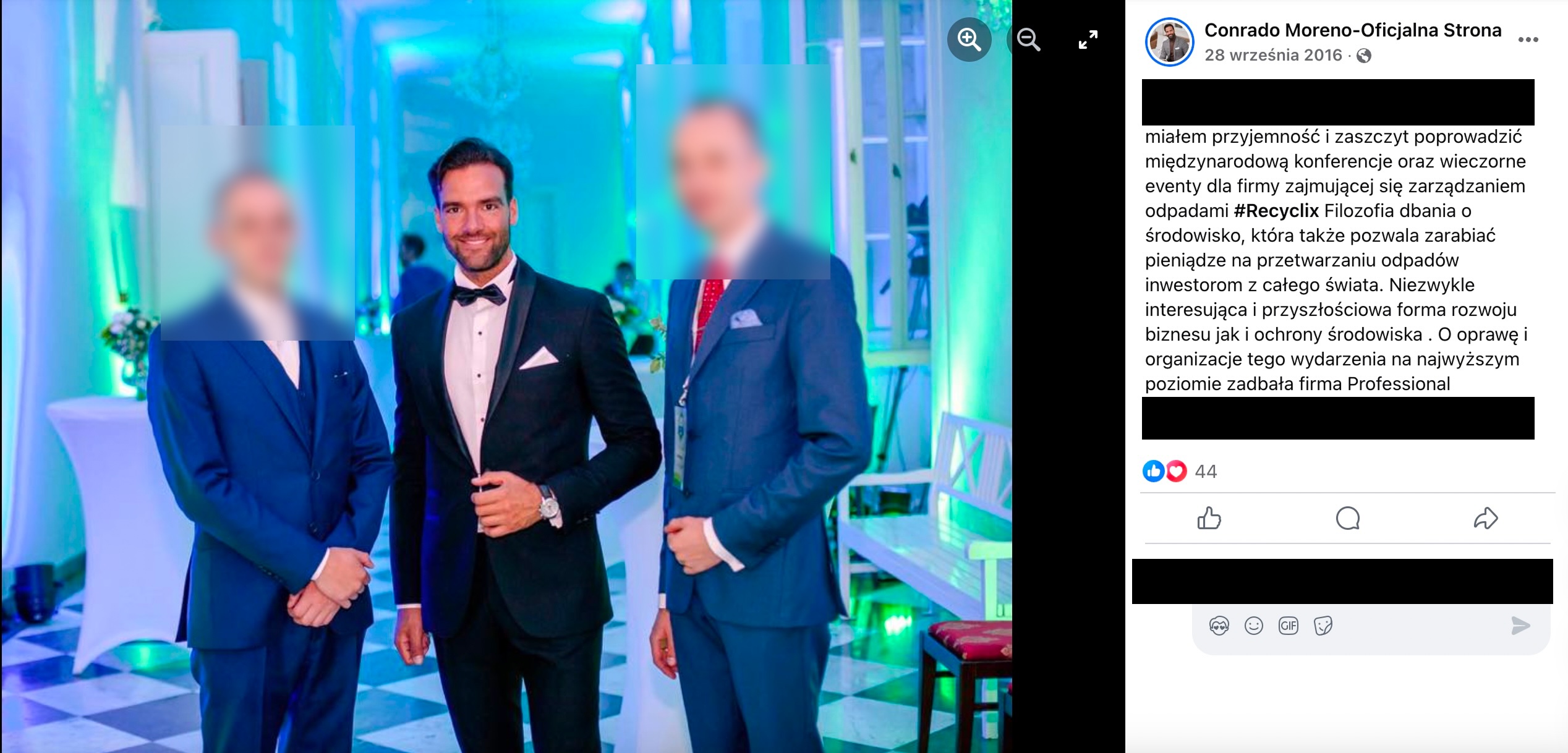

In Poland, the police were starting to take an interest in Recyclix, but the scam was still in full swing. In September 2016, Recyclix organized an open house event in Żagań. The press conference was hosted by Conrado Moreno, a former star of the TV show Europa da się lubić (he refused to speak to FRONTSTORY.PL, stating that he was protecting his image). In the evening, Michał Szpak performed for the guests. Investors were also supposed to visit Recyclix’s alleged factory — but it turned out to be a ghost factory. We could not find its address anywhere.

Conrado Moreno at Recyclix’s open days in Żagań. Photo: Facebook

But in December 2016, something strange happened. Recyclix stopped accepting payments to its company account and instead instructed customers to send money to the account of Bepay Limited, a UK company run by a 26-year-old Latvian. A week later, Recyclix’s account was moved to a bank in the Czech Republic. Why? The answer is simple: the creators of Recyclix were beginning to move their assets. They were preparing to flee with the money.

Some users of the platform were surprised: why would a Polish company need a shell company with a foreign account? But business was still booming.

The crash came in early 2017. After several weeks of delayed payments, Recyclix announced that the landfill in Brożek, where they allegedly stored their waste, had burned down. The valuable material — in which, according to the company, 100,000 people had invested — had supposedly gone up in smoke.

However, as Dziennik Gazeta Prawna later revealed, the landfill actually belonged to someone else. The fire was merely an excuse to declare that half of the investors’ money had disappeared.

Financial Supervision Authority: Oh Dear, Someone Is Breaking the Law

For those investing in Recyclix, the truth had finally become clear: they had been defrauded. But how did the Polish state respond to the pyramid scheme?

On February 20, 2017, the Warsaw prosecutor’s office launched an investigation into fraud (ref. PO II Ds.136.2017). And the Financial Supervision Authority? It cautiously stated that it “sees indications that Recyclix may have violated the law.” It wasn’t until the fall that the Office of Competition and Consumer Protection officially declared Recyclix a pyramid scheme. For Recyclix customers, the game had long been over.

The company’s managers disappeared. They were last seen in February 2017 in Brazil, where — as usual — they were promising to build a factory.

And what about the promised construction in Łobez? Recyclix left behind debts to the city and unpaid contractors. All that remained of the much-hyped investment were the skeletal frames of unfinished buildings.

Investors came to the grim realization: it had all been a scam. There were no functioning factories — and the ones they had been shown were merely staged.

After the collapse, the industry magazine Plastics Review scrutinized footage from one of the so-called factories and published a damning description: “A primitive, inefficient sorting line, working conditions that violate basic health and safety requirements, general chaos, piles of waste in the open air, and a dilapidated, rusty warehouse crammed with rubbish.”

Recyclix open days. Photo: Plastics Review

Chaos: Effectively Covering Their Tracks

By the fall of 2016, the creators of Recyclix began skillfully evading scrutiny. Be warned: it’s hard to keep up with them — and easy to lose track.

Lithuanian national Aleksandr Šuranovas, the company’s owner, stepped down as CEO. He appointed another Lithuanian as his replacement — only to resume the role himself four months later. In March, he granted power of attorney to a Ukrainian national, who then transferred the company shares to himself. Two months later, Šuranovas sued him, demanding the shares back.

What was going on? Most likely, this was just another layer of deception — a smokescreen for investors who had already sunk their money into a pyramid scheme. The same pattern would emerge later with Juicy Fields, when the scheme’s creators also accused their associates of taking over shares and stealing funds.

Messages from the “new management,” allegedly tied to the Ukrainian, began appearing on the Recyclix website. They accused their predecessors of embezzlement and bluntly declared the business a pyramid scheme. They published names and photos of those they claimed were behind the fraud. According to their statements, the main organizer was Sergei Berezin — the same man who would later be accused by Spanish prosecutors of running Juicy Fields.

Meanwhile, Recyclix’s social media accounts insisted the company had been taken over by fraudsters, calling the new Ukrainian owner a “front man.” Investors were encouraged to log in to their Recyclix accounts via the website of Aleksandr Sivaks — the same man who had been photographed shaking hands with President Duda.

Confused investors could no longer make sense of the web of names, companies, investigations, and lawsuits.

And the prosecutor’s office?

Pyramid: Clues Lead to Russia

In Poland, the Recyclix case has sat with the prosecutor’s office for years. Meanwhile, in Finland, there has already been a verdict for laundering money tied to the Polish pyramid scheme: in 2022, a court convicted Latvian national Sergejs Vasiljevs and his accountant for laundering €1.14 million stolen in the Recyclix scandal. It’s unclear what directly connects them to the Recyclix operators — apart from the fact that, at one point, investors were instructed to send funds to an account linked to Vasiljevs’ son.

In short: three years ago, a Finnish court (unfortunately, not a Polish one) determined that money had flowed from Recyclix to a Finnish company, and from there to businesses in Lithuania, Cyprus, and the UK. €160,000 went to a company run by Vasiljevs’ son. What happened to the remaining €39 million? We don’t know. The Polish prosecutor’s office has recovered only €320,000.

The Finnish authorities recognized this as an international scandal. During their investigation, they reached out to other countries for leads. Latvia responded that Aleksandr Šuranovas — Recyclix’s official president — was merely a front man. According to Latvian authorities, the company was actually controlled by Mark Kowal, Dmitry Paladi, and Alexander Sala. But those names, they said, were fake. Sala was really Aleksandr Safronov; Kowal, Sergei Berezin; and Paladi, yet another Russian using a false identity.

According to Recyclix newsletters, Safronov was responsible for the company’s accounting department. He is one of the few people from the group not currently in hiding. His LinkedIn profile shows he now works for a Swiss company and previously held jobs in Latvia and Russia. There’s no mention of Recyclix — his CV has a gap from 2015 to 2021. Today, he works in the cryptocurrency sector. When FRONTSTORY.PL contacted him about his involvement with Recyclix, he did not respond.

And what about Sergei Berezin — the Russian we introduced at the beginning of this article? Two years after Finnish and Latvian investigators identified him as one of the masterminds behind Recyclix, he launched Juicy Fields — another pyramid scheme, this time defrauding investors of a record €645 million.

Investigators: Gathering the Necessary Information

Juicy Fields was a near-copy of Recyclix — except that instead of waste processing, it offered investments in medical marijuana cultivation. Once again, the company was fronted by strawmen. Once again, the real leaders used fake names. In this new scheme, Berezin operated under the alias Paul Bergolts — and became the main shareholder of the German company that supposedly created Juicy Fields.

Before becoming head of security at Juicy Fields, Russian Igor Kekszin worked with the notorious Yevgeny Prigozhin, founder of Russia’s Wagner Group. A figure with a disturbing CV – but it was he who, in 2024, told Deutsche Welle journalists, authors of an excellent podcast on the scam called Cannabis Cowboys, about his leadership at Juicy Fields. He also revealed the real names of the main actors in the scandal to a team of journalists from, among others, the Danish DR.dk, the Swedish Svenska Dagbladet, the Dutch BNNVARA, and the German editorial offices of Paper Trail Media, Correctiv, and Der Spiegel.

Thanks to Kekszin’s confession, we now know that Sivaks’ daughter worked at both Recyclix and Juicy Fields (she was arrested by the Spanish prosecutor’s office; her father was not). We also learned that Russian national Vitaly Markevich, the number two at Juicy Fields, was responsible for the IT systems of both pyramid schemes. It came as no surprise that he operated under the alias Vasily Kandinsky (previously, at Recyclix, he had used the name Janusz Majewski).

The pyramid scheme we are describing is a major scandal: Recyclix alone defrauded its customers of at least €39 million, with investors losing an additional €100 million in bitcoin. Juicy Fields defrauded another €645 million.

Did the Polish prosecutor’s office know that Berezin, Safronov, Sivaks’ daughter, and Vitaly Markevich should have been considered suspects in its investigation?

People in the Pyramid Scheme: Who’s Who?

Norbert Antoni Woliński, spokesman for the Warsaw-Praga prosecutor’s office, was laconic: “The necessary information has been obtained” from the Latvian and Finnish authorities. The prosecutor’s office will not meet with us. Jacek Bilewicz, who led the investigation and is now Deputy Prosecutor General, will not meet with us either.

Robert Jabłoński, a police officer from the Warsaw Police Headquarters who worked on the Recyclix case, did agree to speak with us. He talks about the case with passion and expresses frustration that they were unable to catch all the criminals, prove their guilt, or recover the stolen money.

The investigators have failed: as FRONTSTORY.PL has established, the only remaining suspect in the Polish investigation is Aleksandr Šuranovas, the Lithuanian “front man.” But he could not have been the mastermind behind Recyclix, if only because, in 2016, he spent several months in a Danish prison for fraud and forgery.

Why didn’t the prosecutor’s office issue arrest warrants for Berezin and his colleagues? “Allegations alone are not sufficient to bring charges or issue an arrest warrant,” Jabłoński told FRONTSTORY.PL.

Conclusion: the authorities know who was behind Recyclix — but knowing is not the same as proving.

The Polish prosecutor’s office also suspects Šuranovas of fraud, and he faces up to 10 years in prison. But the man who holds the key to uncovering who was truly behind the pyramid scheme was simply questioned and released on (a small) bail. In the prosecutor’s office’s newspeak, “procedural steps were taken and preventive measures of a non-custodial nature were applied against him.” He was not banned from leaving Poland.

Šuranovas left for Lithuania. The Warsaw-Praga prosecutor’s office later learned from FRONTSTORY.PL that he is now suspected of sabotage for the GRU.

Prosecutor: We Cannot Cope with Scandals

Today, more than eight years after the scandal broke, there is still no end in sight to the investigation.

Almost a year ago, in July, the prosecutor’s office — which had already questioned around 3,000 witnesses — announced that it was looking for more victims of the scandal.

“The €39 million was stolen only from those we managed to reach. The total losses are more likely to be in the hundreds of millions of euros,” Jabłoński told FRONTSTORY.PL.

Did investigators really need to question thousands of witnesses and continue looking for more? Did the investigation really have to drag on for eight years? We asked a prosecutor experienced in economic crimes.

“I once handled an internet fraud case where three thousand people were questioned. We wrapped it up after seven years. There is now a provision that allows victims not to be questioned if it’s unnecessary, but it has only been in force since 2019. Before that, the prosecutor’s office was obliged to question all witnesses ex officio. Announcing that they are seeking additional victims is also a legal obligation,” explained the prosecutor (who wished to remain anonymous) in an interview with FRONTSTORY.PL.

Almost four months ago, the investigation into Recyclix was suspended. The reason: the prosecutor’s office had requested legal assistance from several EU countries and is awaiting responses.

CEO: Planting Bombs

In July 2024, a package sent by Šuranovas via DHL from Lithuania exploded at Leipzig Airport. A day later, a similar package detonated in a truck carrying parcels near Jabłonowo, close to Warsaw. The next day, another package exploded at a DHL facility in Birmingham, UK. A fourth package was intercepted by the Polish Internal Security Agency (the exact time and location have not been disclosed).

All four packages had been sent on the same day from Vilnius. A few months later, The Wall Street Journal published a security camera still from a DHL office in Vilnius showing the bomber. It was Šuranovas, our Recyclix “front man.” A trained eye could recognize him at the DHL counter — this time wearing a T-shirt and shorts instead of a suit.

Šuranovas was acting on behalf of Russian intelligence.

Were the Recyclix and Juicy Fields pyramid schemes operations run by Russian services?

“It is possible that the GRU used Šuranovas because of his criminal background. But the Russian services usually employ small fry for tasks like this. Someone else would have been in charge of coordinating the operation,” said a person familiar with the Polish investigation into Russian sabotage.

Aleksandrs Šuranovas at a shooting range in Vilnius. Photo: Šuranovas’ Facebook profile

However, it cannot be ruled out that the perpetrators are more closely linked to the Russian security services.

“In Russia, the world of the intelligence services overlaps with the world of economic crime. Jan Marsalek, the Austrian who set up the Wirecard pyramid scheme in Germany, turned out to be a GRU spy. He was the one who ordered the kidnapping or murder of investigative journalist Christo Grozev. And even when such criminals are not directly controlled by the services, they can operate semi-officially in Russia. They are tolerated as long as they do not harm Russian interests,” said Robert Nogacki, a lawyer at Kancelaria Skarbiec and a specialist in commercial law, speaking to FRONTSTORY.PL.

After the collapse of the Juicy Fields pyramid scheme, Markevich, an IT specialist for both pyramids and Berezin’s second-in-command, managed to flee to Russia. Shortly after Russia’s attack on Ukraine, he opened a factory near St. Petersburg producing drones for the Russian army.

What are the drones for?

“For agricultural purposes, forest fire warning and land surveying, as well as for destroying Elon Musk’s satellites and protecting the national Wi-Fi network, which I want to launch using my drones,” Markevich told journalists investigating the Juicy Fields scandal a few months ago.

To Be Continued

Almost no one in Poland has heard of it, but half of Europe is still reeling from the Juicy Fields pyramid scheme, run, as we now know, by Russians. We were the first to uncover its Polish connections.

This chapter of the story of Russian fraudsters is even stranger and more twisted than the Recyclix scheme, where they first began their operations. Here, the action unfolds even faster — again spanning several continents, private jets, and dazzling luxury.

We have established that one of the figures in the Juicy Fields pyramid scheme — a German count — set up a shell company in Lower Silesia and (until recently) invested in palaces and tenement houses without anyone intervening.

The dubious count is now arrested, and investigators are working to secure his assets — but in the meantime, his businesses are being supported by the former head of the Polish stock exchange.

Will the Polish prosecutor’s office be fooled again? Read the second part of the investigation on VSquare.org.

Are you a victim of Recyclix? Report it to the prosecutor’s office. The investigation is still ongoing – details here.

The Polish version of this story was published on FRONTSTORY.PL.

Subscribe to “Goulash”, our newsletter with original scoops and the best investigative journalism from Central Europe, written by Szabolcs Panyi. Get it in your inbox every second Thursday!

| This investigation is part of the CIJI project, supported by the European Union. |  |

| All opinions expressed within the scope of this project represent the opinion of their authors and not those of the European Union |  |

An investigative journalist at FRONTSTORY.PL, Daniel Flis previously was on the investigative team of OKO.press and Gazeta Wyborcza. OCCRP Research Fellowship Program recipient. Participant in international investigative projects of the Reporters Foundation.