Illustration: Filip Ysenbaert(De Tijd) 2023-10-24

Illustration: Filip Ysenbaert(De Tijd) 2023-10-24

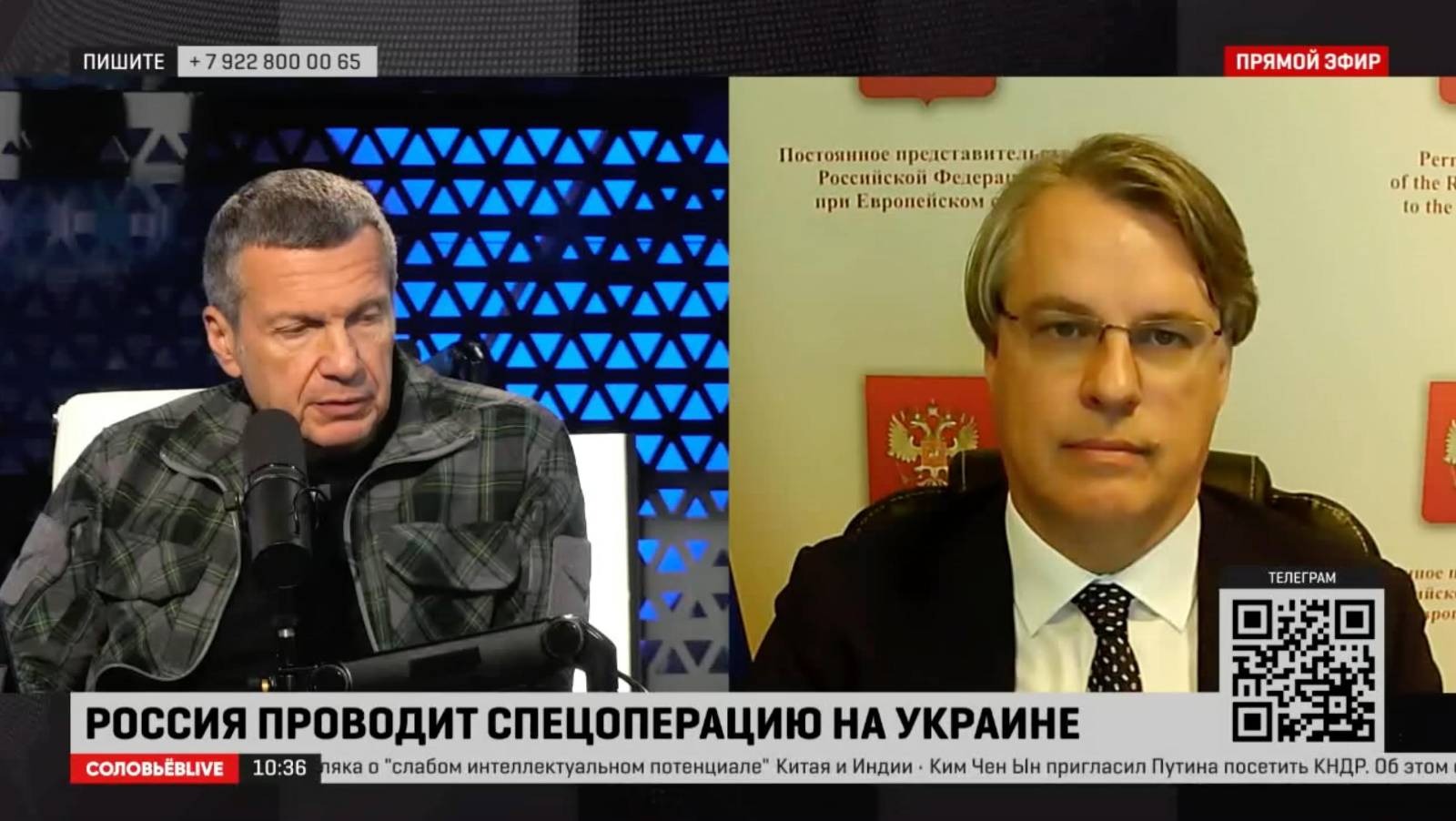

Russia’s diplomatic mission to the EU is led by Kirill Logvinov, whom Belgian counterintelligence suspects to be carrying out Russian foreign intelligence functions in Brussels. Despite this, the European Commission has so far refused to expel Logvinov or other “diplomats” suspected of espionage.

Around the corner, barely 200 meters from the office of Belgian Prime Minister Alexander De Croo, near the federal and Flemish parliament and the royal palace, is a tall building: the Permanent Mission of the Russian Federation to the European Union. The Russian diplomatic headquarters is 42 meters wide and more than 2,200 m² in size. It is located in the heart of Brussels, along the Regentlaan, right next to the American embassy. The Soviet Union acquired the building, known as “Hotel Brugmann,” after World War II and originally used it as its trade mission. They made it Russia’s Permanent Mission to the European Community in 1988.

After Russia’s full-scale invasion against Ukraine, on March 18, 2022, the president of the European Parliament, Roberta Metsola, declared that Russian and Belarusian diplomats in Brussels were banned from entering the European Parliament. “There is no place in the House of Democracy for those who want to destroy the democratic order,” Metsola said. Since then, Russian diplomats delegated to the EU have not been able to properly carry out their official tasks. Contacts with the European institutions are still purely technical, intended only to settle practical issues for the Russian diplomatic corps in Brussels and the EU in Moscow.

Moreover, two weeks later, on April 5, 2022, 19 diplomats from the Russian Mission to the EU were declared persona non grata and expelled from the country. These diplomats were, in reality, likely working as undercover intelligence officers.

Shortly after Russia’s attack on Ukraine, the Belgian State Security Service (VSSE) shared intelligence with the European External Action Service (EEAS) in which they were identifying certain Russian diplomats as spies, along with details of their hostile activities. At the time, Western countries expelled hundreds of Russian diplomats, many of whom were judged by their respective intelligence agencies to have been acting as Russian intelligence agents.

The EU also seemed to go along with the expulsions. Behind the scenes, however, they opted not to sanction every Russian spy under diplomatic cover whose names the Belgian authorities had passed onto them. As the Russian representation to the EU is located on Belgian territory, counterintelligence duties are carried out by the Belgian authorities, but only the European Commission and the EEAS can decide on expulsion.

As a result, several Russian diplomats still working in Brussels are able to carry out their clandestine espionage activities and influence, a new #ESPIOMATS international investigation by VSquare and partners—De Tijd (Belgium), Paper Trail Media and Der Spiegel (Germany), Expressen (Sweden), Delfi Estonia, LRT (Lithuania), Frontstory.pl, ICJK.sk and the London-based Dossier Center—reveals.

We found that one of the people still operating in Brussels who is suspected to be a Russian spy is the permanent mission’s top diplomat, Kirill Logvinov. Our investigation also revealed that, while the Belgian government and VSSE wanted to take more decisive action, the European Commission and EEAS seemed to prefer a softer approach.

Belgium’s government introduced its own ban on diplomats at the Russian Embassy in Belgium—which is separate from the Russian Permanent Representation to the EU—by expelling 21 diplomats on March 29, 2022. However, they lacked the authority to decide on what should be done with the permanent representation.

Belgian Justice Minister Vincent Van Quickenborne, in a short reply to our request for comment last Friday, said only that “the accreditation of diplomats at the Permanent Representation to the EU is decided by the European Commission, not the Belgian government.” (On the same evening, Van Quickenborne announced his resignation following Belgium’s failure to prevent a terrorist attack in Brussels that killed two Swedish football fans.)

We do not know why exactly the European Commission decided to maintain Logvinov’s diplomatic accreditation. Last summer, the Commission even received a request from two MEPs who said that one of Kirill Logvinov’s tasks was to infiltrate the circle of Commission Vice-President Valdis Dombrovskis from Latvia. “This was the reason why he caught our attention,” one of the MEPs, Petras Auštrevičius from Lithuania, told us, highlighting that Dombrovskis “is also in charge of macro-financial support for Ukraine.” The request included three questions and referred to the findings by the EU Observer and the Dossier Center, who were the first to report suspicions of Logvinov’s activities in Brussels.

While the MEPs were awaiting a response, Logvinov became the Russian mission’s interim head.

EU High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy Josep Borrell’s response was late, only arriving after more than two months instead of one, Auštrevičius recalled. “The European Commission has applied measures to assess the threat on a consistent basis,” Borell eventually replied, adding that detecting, deterring and responding to Russian intelligence activities “has always been a high priority for the Commission.”

“The answer that we received was a very general answer, basically saying nothing about whether or not any action would be taken against him,” Auštrevičius said. “Logvinov is apparently not an ordinary actor. He is experienced enough, and he has been given great powers. This confirms once again that we are unlikely to have made a mistake with our first three questions, given that such rumors do not go around empty,” he added. Auštrevičius also confirmed hearing a “legend” that the Belgians shared information on the Russian diplomat’s intelligence activities and that “it was the European Commission’s decision not to take further action against Logvinov”.

The European Commission’s spokesperson for foreign affairs and security policy, Peter Stano, replied in writing to our questions that the Commission does not comment on questions about individual diplomats. He reiterated Borrell’s message to MEPs last autumn: the EEAS and the Commission have applied appropriate measures to assess the threat: “All this is confirmed by continuous security briefings to increase counterintelligence awareness among personnel. A crucial part of all these safety procedures is intensive cooperation with the safety authorities of the Member States and other EU institutions.”

Logvinov and the Russian Permanent Mission to the EU did not react to our request for comment.

Networking with Russia’s friends in Brussels

The Russian diplomat who has been leading the mission for over a year now, 48-year-old Kirill Logvinov, is, to the knowledge of VSSE, an intelligence officer working for the SVR. Officials from two European intelligence agencies independently confirmed to us that Belgian counterintelligence regards Logvinov as a Russian foreign intelligence officer, while VSSE itself declined to comment.

Logvinov’s official resume, of course, does not reveal his intelligence function. In the 1990s, he graduated from MGIMO, the Moscow State Institute of International Relations of the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. (One European intelligence official who spoke to us describes MGIMO as the main talent-hunting ground for Russia’s foreign intelligence service.) Since then, Logvinov has worked as a press and cultural attaché at the Russian Embassy in Vienna; as head of the NATO desk at the Russian Foreign Ministry; and, since 2004, at the Russian Permanent Representation in Brussels. He also spent four years in Berlin at the Russian Embassy from 2010 to 2014. His current rotation in Brussels started in 2018.

On September 27, 2022, Logvinov became the new head of Russia’s Permanent Mission to the EU as chargé d’affaires ad interim. He succeeded 68-year-old Russian politician and diplomat Vladimir Chizhov, who had been leading the Russian Permanent Mission to the EU for 17 years. Chizhov ended up on the EU’s sanctions list in December last year because, after leaving Brussels, he became a member of the Russian Federation Council, the upper house of the Russian parliament.

Just one week after his appointment, Logvinov began a months-long series of one-on-one meetings with diplomats from Belarus, Kazakhstan, Syria, Lebanon, Turkmenistan, Tajikistan, Egypt, Azerbaijan, Kyrgyzstan, and Venezuela. “We will continue with our work to meet the goals set for us by the leaders of our country and ministry,” he told Russian media. “The geopolitical situation has changed the nature of our work, but our goals remain unchanged: to promote rapprochement with Russia in Brussels.” After that, Logvinov welcomed diplomats from China, Iran, Cuba and Nicaragua. African diplomats were also invited to a reception in May at which, among other things, investments by sanctioned Russian companies were discussed.

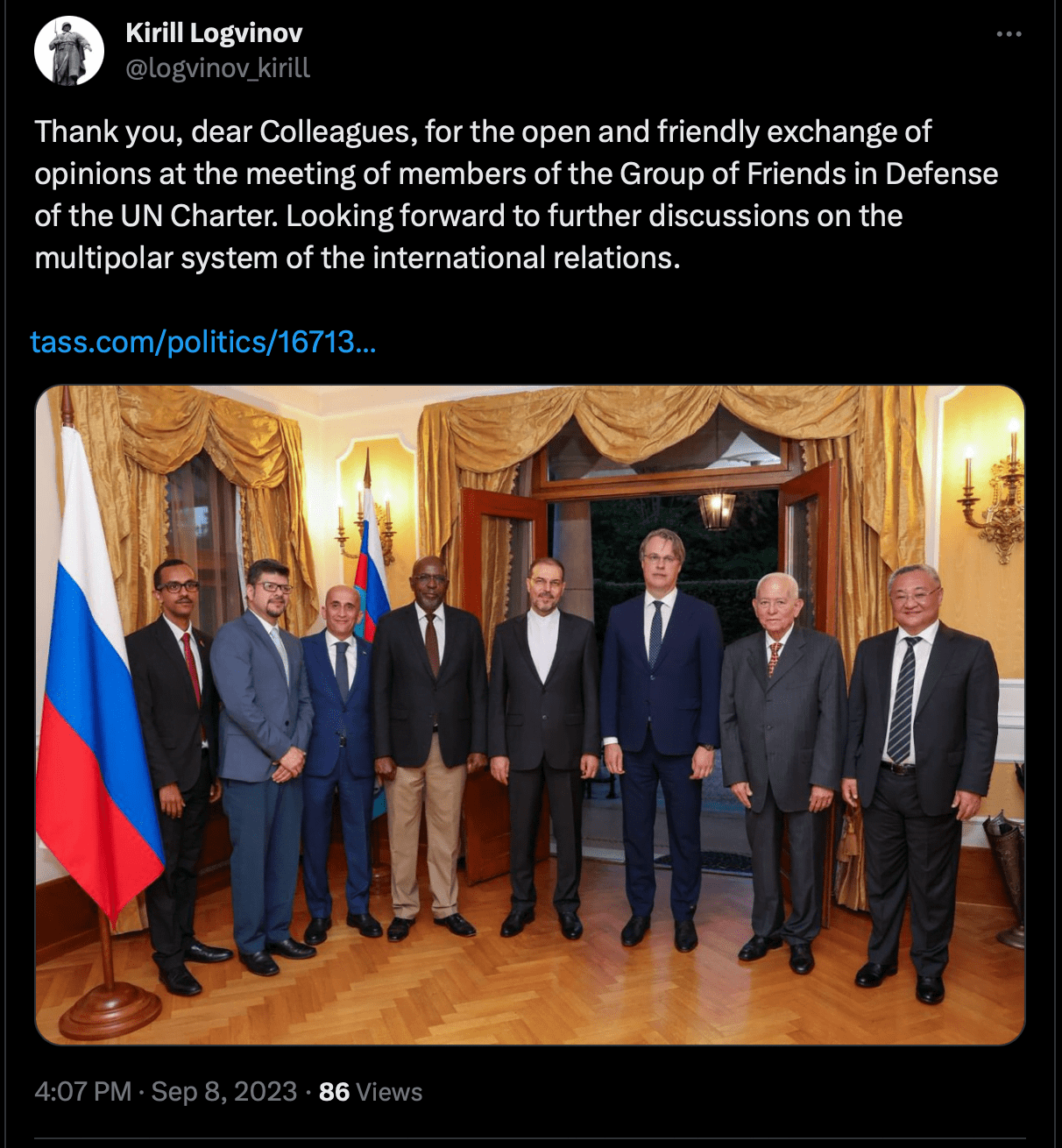

In June, a reception was held for high-ranking diplomats from Latin America and the Caribbean, who were shown the Russian propaganda film Tell the World about your Motherland. Military, security and other technological collaborations against the US and its allies were also on the agenda. The same thing happened a month later with diplomats from Southeast Asian countries. At the same time, Logvinov told a Russian news agency that there was “a hybrid war against Russia” and that his country would “not just forget and forgive” the EU decisions. This was followed by a September meeting in the building on Regentlaan with countries from the “Group of Friends in Defense of the UN Charter,” which also includes China, Belarus, Russia, North Korea and Iran. At the same time, the EU mission spread even more propaganda, such as a “documentary film” called, Tanks for kidneys: investigating cases of organ trafficking in Ukraine.

Russian diplomats are not allowed to enter EU buildings, such as the European Parliament. But the Logvinov-led mission has found a way around this in that it often hosts MEPs at their own events.

In June 2023, for example, Milan Uhrík, a far-right Slovak MEP and chairman of the neo-Nazi affiliated Republika party, showed up at one of Logvinov’s receptions. “There are many diplomats from all over the world here, and I had especially good conversations with Russians, Belarusians and Syrians. (…) We must not close the door to dialogue that alone can ensure peace and create opportunities for affordable energy and raw materials for Slovakia,” the pro-Russian Slovakian politician wrote in a Facebook post, adding that his party’s power is “noticed by the whole world” (at the September 30 Slovak elections, Republika eventually fell short of entering parliament).

Uhrík replied to our comment request claiming that he doesn’t know and didn’t meet Logvinov at the reception. “I don’t think it’s right to be guided only by media speculation. Many things are written in the media,” he said about previous reports about Logvinov’s alleged ties to Russian intelligence. “I am not afraid of agents, I already have enough experience with negotiations in high politics and I am always extremely cautious when communicating with anyone,” Uhrík concluded.

Urmas Paet, a long-serving Estonian MEP, was extremely critical when we asked him to assess the EU’s action to prevent Russian intelligence and influence operations in Brussels. According to him, Russia’s influence was particularly visible before the new wave of aggression against Ukraine broke out last year. “In the case of the European Parliament, for example, Russia has repeatedly succeeded in getting MEPs to go on pseudo-election observation missions to Crimea and eastern Ukraine, even though this was against official EU policy,” Paet recalled. In addition to the dozens of MEPs representing pro-Russian positions in official votes, Paed said there are some amendments to drafts critical of Russia that aim to water down the legislation (Delfi has reported on such examples before).

Logvinov is not the only spy left

In addition to holding public events, Russian diplomats also continue to conduct clandestine activities behind the scenes. For example, the remaining Russian intelligence officers in Brussels could continue to work together with their Belarusian colleagues who have not been expelled.

The Embassy of Belarus in Brussels is still home to several intelligence officers from both the state security service KDB and the military intelligence service of Belarus, according to Belgian sources with knowledge of national security matters. They, too, were given “slot positions” at the embassy that are always given to intelligence officers. The Belarusian spy diplomats have also been very active in recruiting sources in recent years. In addition to monitoring the Belarusian diaspora in Belgium, they focus on European institutions and EU policy.

Belgium’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs has not revealed which Russian diplomats are still working in Brussels today. De Tijd tried to obtain data through a public information request. However, despite positive advice from the relevant committee, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs continued to withhold the lists of names.

Nevertheless, the #ESPIOMATS investigation managed to identify more undercover intelligence officers besides Logvinov working at the Russian EU Mission. On the Russian permanent mission’s website, there is no longer a list of names on the “diplomatic staff” webpage. It was removed after the full-scale invasion of Ukraine. But with the Wayback Machine tool, we were still able to find out which Russian diplomats were active here until the invasion and which were not expelled in April 2022.

An archived version of the web page from April 21 last year did not show the list of names. But an earlier, still preserved version from February 4 last year contained 61 names. These included the now departed Chizhov, who still led the mission at the time; the current chief Logvinov, who held the title of “Deputy Permanent Representative (political affairs)” at the time; and 59 other Russians, out of whom 19 were later expelled. On another Russian government website, we found a list of names for Russia’s mission to the EU, but it appears to be outdated as there are still names on that site that were only on older versions of the deleted list.

After compiling the list of names of the other 40 Russian diplomats who were not expelled from Belgium, the London-based Dossier Center helped us by carrying out research on the diplomats’ backgrounds. Dossier’s findings indicate that many of them are also affiliated with Russian intelligence.

For example, Dimitry Vishnyakov, a 42-year-old adviser to the Russian EU Mission who was responsible for “administrative affairs,” received training at the academy of the Russian security service FSB from 1998 to 2003, according to our data. At that academy, Russians are trained to work as intelligence officers in either the FSB or another intelligence service. Yet another 42-year-old Russian diplomat, Dimitry Golovenkin, who is second secretary in charge of commercial affairs, appears to have given the headquarters of the military intelligence service GRU as his Russian home address.

However, MEPs told journalists working on the #ESPIOMATS project that no outreach or training on how to recognise and prevent the dangers of Russian intelligence and influence has been carried out in the European Parliament. “There has been nothing like that,” Urmas Paet said. “To my knowledge, no training has been offered. Apart from the recommendation to remove TikTok from personal devices, there has been no specific guidance on how to protect your communications, for example, nor on how to behave in case of possible approaches by foreign intelligence officers,” Slovak MEP Martin Hojsik added.

Carousel of spies

A secret document that VSSE provided to the Belgian government in March last year, obtained by De Tijd, indicates that the Belgian State Security Service already knew a lot about the illegal activities of Russian diplomats. For example, according to the document, one of the expelled advisers, Aleksandr S., was said to have had frequent contacts with other Russian intelligence officers and also tried to recruit human sources in Belgium. Another expelled diplomat, Anton A., whose link to the SVR was confirmed to journalists working on the #ESPIOMATS by various European intelligence agencies, was collecting economy, energy, and science related intelligence in Brussels.

According to various European intelligence agencies, attaché Andrey Z. worked for the technical department of the SVR. The former first secretary of the Russian mission, Timur A., was said to have gathered political intelligence for the SVR in Brussels. Counselor Alexey C. and second secretaries Nikolay K. and Aleksandr Z. also gathered political intelligence for the SVR up until their eventual expulsion.

The Russian EU mission is a carousel for spies. When an officer of the SVR’s political team, Ivan K., was sent to Brussels as a third secretary for the Russian mission, he was taking over that position from another SVR colleague. Ivan K. continued his predecessor’s work as an intelligence officer and took over handling his informants. Other expelled diplomats in the EU mission worked for other Russian intelligence services such as the military GRU and the domestic FSB. There, too, continuity was always ensured. For example, the suspected FSB officer Dmitry K. was replaced by another FSB officer. He appeared to be particularly interested in terrorism-related issues. The spy diplomats also appear to have particular portfolios as another, now-expelled diplomat, Aleksandr T., focused mainly on nuclear issues.

Former senior Hungarian counterintelligence officer Ferenc Katrein told VSquare that the well-organized succession of tasks and handling of informants is the regular modus operandi of Russian intelligence. According to him, the outgoing Russian diplomat usually holds a clandestine “goodbye-welcome meeting” for the informant and the incoming official. This is where the informant is personally introduced to the incoming Russian diplomat as his or her new handler officer. “Sometimes, these meetings take place in third countries for safety reasons,” Katrein added.

The analysis of the older lists of names of the Russian EU Mission shows that 10 of the 19 expelled intelligence officers had been working in Belgium for years. For example, the names of suspected FSB officer Dmitry K. and SVR officer Aleksandr S. are already on lists from July 2016, per our research using the Wayback Machine.

According to Belgian national security sources with knowledge of the situation, diplomats of the Russian mission to the EU sometimes barely set foot in the official building of the mission on Regentlaan, where they are supposed to work as diplomats. Instead, they do go to the Russian Embassy in Belgium—in Uccle—where Russian intelligence keeps their real technological and operational headquarters. The satellite dishes and other equipment on the roofs of the embassy grounds in Uccle are a clear indication of this, as we revealed earlier this year as part of our ESPIOMATS investigation. However, Belgium cannot do anything about this for diplomatic reasons either.

Meanwhile, according to MEPs interviewed, the European Union and its branches have not done enough to prevent the Russian intelligence threat in Brussels. “It is shocking to me that [Logvinov] has not yet been kicked out. If the Belgian intelligence authorities requested his expulsion, I would be very interested to know the reasons why the EEAS has not acted. I hope that, following this revelation, the European Parliament will investigate this particular case and demand that the EEAS act,” Slovak MEP Martin Hojsik said.

Petras Auštrevičius highlighted that the Russian diplomat is visibly active these days. “I understand that he has been given the task of working with the Russian diaspora here in Brussels, as well as throughout Belgium. He is often mentioned as having done something,” the Lithuanian MEP added.

“It is clear that we cannot accept that we have information that relates to pure espionage and not act on it, but of course, the information must be confirmed,” Swedish MEP Tomas Tobé said. “It’s no secret that there is a lot of talk about Brussels as the ‘spy capital’ so unfortunately, this is a reality that we have to deal with,” he added.