Illustration: Marek Studzinski 2025-03-19

Illustration: Marek Studzinski 2025-03-19

Germany’s political structure and electoral system favors a coalition of the major parties. But with a growing movement of the far-right — and the Alternative fur Deutschland (AfD) doubling their vote share — disinformation tools have been used to push electoral agendas towards narratives favouring the Kremlin. Meanwhile, Russian election interference continues to expand throughout Europe. Investigace.cz investigated the Russian Doppelgänger campaign last summer, and numerous additional campaigns have been identified as having produced a bewildering variety of digital content on different social media platforms. How effective are these activities? That part is still unknown.

Investigace.cz’s Paul May spoke with Brian Liston, a senior threat intelligence expert at Recorded Future, one of the world’s largest cybersecurity and intelligence companies. Liston works for Recorded Future’s Insikt Group, which tracks disinformation actors and their campaigns on social media.

Outside of the typical Ukraine focus, disinformation attempts in the German elections included personal attacks on senior political figures from different parties. Is it clear that the Russia-funded campaigns collectively favor certain parties? We noticed that AfD didn’t seem to be a target of any attacks in these campaigns…

Yes, it’s even more apparent than usual. That’s likely to be because of AfD’s alignment with Russian strategic interests. We observed that the content had just been heavily anti-CDU (Christian Democratic Union, the party which won the largest vote share) coalition. One of the operations, called “Operation Overload,” posted AI-generated images of a dystopian Germany under the CDU, and then a bright and happy Germany under an AfD ruling coalition. It included the logos of those political parties. So there’s a clear bias towards the AfD.

More subtle tactics have included character attacks on individual German political figures.

In general, the campaigns focus on issues such as immigration, Germany’s role in Europe and NATO, alignment back to Russia and Russia’s interests in Ukraine.

Did you observe any campaigns featuring smaller parties, for example Die Linke, or BSW?

No. The content has been deeply anti-coalition, with content opposing the CDU, SPD (Social Democratic Party) and Greens.

You mentioned Operation Overload, but a range of disinformation campaigns, asserted by some analysts to be instruments of the Russian government, have been deployed in Europe. Different outlets identify them by different names: CopyCop, Doppelgänger, Overload, Undercut. How and do you separate them, and what are the differences?

We separate them by their modus operandi — how they behave. But there are a lot of overlaps in content and tactics. We think there is an organizational relationship [different agencies/organizations working on different campaigns but coordinating] as well, because they all share similar infrastructure.

Doppelgänger, for example, is defined by media impersonation — using techniques such as website impersonation, social media amplification via networks of inauthentic accounts (so-called “bots”), hijacked accounts, repurposed accounts — as well as its own brand of some fifty or so WordPress websites over the course of the last two years.

Operation Overload was built from email spam campaigns. The emails link to fake videos on Telegram impersonating Euronews or the Wall Street Journal, or more recently Spiegel. It is video production, and has a persistent quality: they are designed to have a lasting impact, rather than necessarily being sensational or immediately viral. “Overload” and “Doppelgänger” are more related. Operation “Undercut” also overlaps in content and tactics with both, and we anticipate an organizational relationship there, back to the Social Design Agency, a Russian IT firm led by Ilya Gambashidze, which has played a central role in orchestrating disinformation campaigns, including the Doppelgänger project, to influence foreign elections and disseminate pro-Russian narratives.

“CopyCop” is mostly a shared network of websites featuring AI-powered, and specifically LLM-powered content. Overall, they all have distinct signatures, which allow us to track them.

Is it possible to attribute different campaigns to different actors reliably? What types of clues do you look out for?

It’s tough. It was a lot easier with the Internet Research Agency from St. Petersburg, because we were able to identify them by their IP addresses. Overall, we are usually able to trace the campaigns’ origins to Russian speaking actors. For example, we encountered a campaign where, when translated from Russian, there were homophobic slurs, and content directly addressing the US intelligence community. Those particular groups appeared to be deliberately trying to make it obvious to US intelligence agencies who the perpetrators were. It appears that they were trying to let the authorities know who they were.

Activity from CopyCop has been definitively linked to John Mark Dougan, backed by Alexander Dugin’s Centre for Geopolitical Expertise (CGE) and the GRU’s Unit 29155, by Recorded Future. We also adopt some attributions from other intelligence platforms and other researchers, such as from Microsoft.

John Mark Dougan is a former Marine Corps veteran and police officer from the United States known for his involvement in disinformation campaigns. He is currently residing in Russia, where he has been linked to Kremlin-backed operations aimed at influencing U.S. elections. Dougan has been accused of working with Russian military intelligence, specifically Unit 29155 of the GRU, to spread misinformation through fake news websites and deep fake videos targeting U.S. political figures. Alexander Dugin, a Russian far-right political philosopher, is associated with the Centre for Geopolitical Expertise, which has ties to Dougan’s activities.

How do you assess the impact that these campaigns are having? In your report you make quite a confident assessment that there is a limited reach and effect for this activity. Limited evidence of impact doesn’t necessarily mean the impact is minimal…

We’re basing that statement on metrics that are provided to us via the social media platforms. That translates to engagement with the posts themselves. This is not just the total number of views. We’re also looking for cross-posting on multiple platforms, via influencers and different websites.

In most cases, the posts don’t get much outside visibility beyond the networks that are trying to boost them. We will see videos on Telegram first (before they’re promoted in social media) and then we’ll see bots on social media within that network try to continue to boost it by flooding the replies of researchers who reply to the content (like myself), hoping it will be caught and reshared by a prominent influencer.

However, because social media might evaluate this kind of behavior as inauthentic, spammy, and therefore not allow it to be seen, we’re often basing our assessment of campaign visibility on the number of reposts, even relating to different versions of the same content.

Are there any good examples of a successful campaign?

Yes, the biggest one most recently is the USAID video, which was recently shared by Elon Musk and several other prominent figures that we attributed to Operation Overload. The video shows a news broadcast on E! New, claiming that USAID financed the Ukraine trips of celebrities such as Ben Stiller, Orlando Bloom, and Angelina Jolie – claiming amounts like four million dollars for Stiller, eight million for Bloom, and 20 million for Jolie.It took a somewhat different tactic at the time, they were leaning on some particular social media influencers (rather than inauthentic accounts) for their audience. The audience for it was there, and so it grew.

In a similar case last year, after Pavel Durov (the founder of Telegram) was arrested in France, the creators of disinformation campaigns produced a video about the UAE, which claimed that the UAE had suspended the purchase of French jets as retaliation for Durov’s arrest. This video received some fairly prominent attention, helped by being featured by an Indian newspaper. There are a handful of other smaller cases.

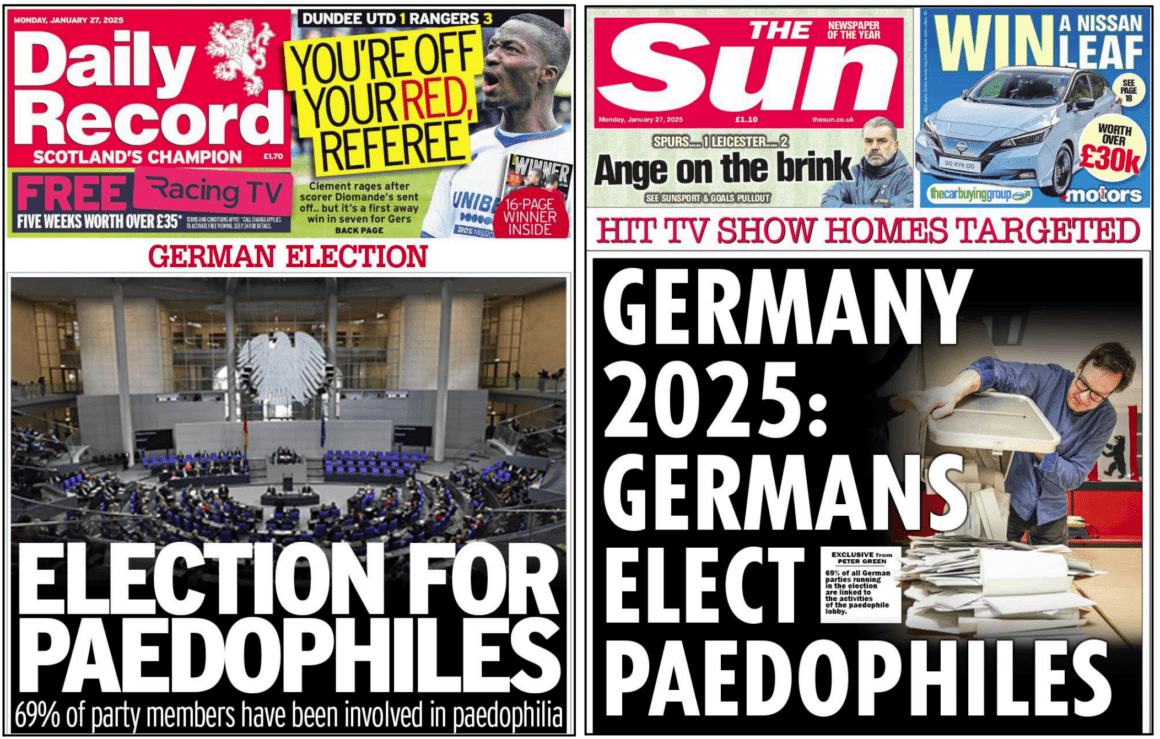

Inauthentic British ‘red-top’ tabloid front pages accuse German politicians of paedophilia Germany, produced by Operation Overload Source: https://archive.is/QQzTx

One example you covered was the imitations of UK tabloids, of what seemed to be just generally negative news about Germany. Is there any evidence that this type of content attracts more engagement?

There is no indication that suggests it’s necessarily doing any better or any worse than their video content. It is an attempt to try another tactic, to see what sticks.

We previously found manipulated front pages of the New York Post, and the New York Daily News in a very similar fashion, in Operation Overload last year. Other tactics include producing fake screenshots of Instagram stories of prominent news organizations, and attempts to create the illusion of citizen journalism, such as (photoshopped) anti-Ukraine graffiti on a public place in a major European city. They make multiple copies of this type of image, as in different angles of this superimposed anti-Ukraine graffiti and deploy them as screenshots: supposedly from CBS, or the New York Times, or the Wall Street Journal.

Picture depicting sculpture depicting Volodymyr Zelenskyy swallowing money, claiming to be situated in Warsaw. Source: X

How is the content and the infrastructure hosted, and what are the latest attempts to dismantle it? Qurium Media Foundation and Correctiv’s investigations have been quite pivotal in revealing the infrastructure involved and enabling providers to make takedowns [of that online infrastructure].

Since September 2024, they have diversified their infrastructure a little more, moving off the European hosting services they were previously on. They have moved to use a combination of some mainstream cloud services or domain registrars. But we’re seeing more of these privacy-focused hosting providers: Flokinet and Vice Temple (an adult content hosting provider).

Such hosting companies are often based out of Iceland, for example, because of the available privacy protections. The campaign operators take this approach in the hope of giving their sites greater persistence, and resilience against future takedown attempts.

But some of the websites of these campaigns end up abandoned. They may tire of having to re-register them, or move infrastructure all the time. A lot of the United States websites, for example, are now entirely offline.

You report that the intention of the campaigns was to deter voters from supporting a CDU-led coalition, but you also suspect that some of the campaigns are just attempting to lower voter turnout overall. How do you measure that?

We can say with some degree of confidence: we don’t anticipate that these efforts will have had a major effect on the result. Nor can we say that these efforts led to an increased vote share for the AfD in this election. These campaigns can also just amplify that sentiment, and effectively “pile-on.”

But it’s also just about attention and engagement: they are financially-bound. The Social Design Agency, one of the designated agencies operating the campaigns, for example, needs to show metrics to the Russian government that demonstrate they are having a perceptible effect. This is perception-hacking. They’re trying to pollute the information environment, and they need to demonstrate they achieved a certain threshold of attention to their employers, because it’s in their contracts.

To what extent are the campaigns regionally-targeted in Germany?

In the past day, a new video titled “District 151” was attributed to the CopyCop campaign. It claimed to show a falsified ballot in Leipzig (district 151) and that an AfD candidate and the party itself was omitted from the top part of the ballot. So that is an example of a campaign clearly localized to a particular district.

But as far as we could tell, the amplification itself was not localized to voters of that area. Bizarrely, it was mainly focused on English-language accounts, often in the UK or in the US, that were promoting the idea that there was major election fraud going on in Germany, which is to say it was more focused on projecting outwards that there was a conspiracy or fraud, rather than trying to convince Germans.

We analyzed the engagement of that campaign and also its amplification — at that point there were some 500,000 views and perhaps some people evidently believed that the video was real. But the views were mostly from people outside Germany. The campaigns are somewhat international, and perhaps there might be hope that it trickles down into the domestic sphere, but we’re purely in the realms of hypothesis here.

The campaigns generally are just trying to get attention, boost engagement, and show evidence of some sort of impact.

Is there any evidence at all that similar operations are being deployed in the Czech Republic, or ever have been? We know that Poland was previously targeted.

We haven’t seen that yet, but we have called it out as a possibility in our report, for a number of reasons: we have seen it in Poland in the past, and we’ve also seen these campaigns in Latvia, France, and Germany. In general, they target countries that are the most opportune for influence. Higher priority areas for them might include Poland, Romania and Moldova, outside of Western news. But I think if Russian actors see a distinct opportunity to engage in influence operations in the Czech Republic, they may pursue it. There needs to be a perceived opportunity. In the UK, we didn’t see anything from these campaigns favoring particular candidates, and it was because, regardless of whoever came to power, there was no prospect of a shift in UK policy towards Ukraine, so the cost-benefit wasn’t seen as being there.

But if the “Ukraine [financing] question” does arise in the Czech Republic, or they see an opportunity to promote the activities of an AfD-style party, I think Russia may take that opportunity.

The Czech version of this investigation was published on Investigace.cz.

Subscribe to Goulash, our original VSquare newsletter that delivers the best investigative journalism from Central Europe straight to your inbox!

Paul May is an ICA-trained anti-money laundering expert and a reporter at the Czech Center for Investigative Journalism, investigace.cz.