Tomáš Madleňák (ICJK)

Zuzana Šotová (investigace.cz)

Illustrations: James O'Brien (OCCRP) 2022-04-13

Tomáš Madleňák (ICJK)

Zuzana Šotová (investigace.cz)

Illustrations: James O'Brien (OCCRP) 2022-04-13

For almost a month, as a part of a joint investigation carried out by OCCRP and journalists from several media outlets, called Russian Asset Tracker, we have been examining where and how the assets of Russian oligarchs are hidden in Poland, Slovakia, and the Czech Republic.

Poland

Unlike in Western European countries, where Russian oligarchs often hold their wealth directly in real estate, companies, yachts, and luxury goods, in Poland the business activities of these ultra-rich Russians resemble a matryoshka – a set of wooden nesting dolls in which larger dolls hide smaller ones.

On the Polish market, Russian oligarchs make only indirect profits. Typically, they are the ultimate beneficial owners of legal entities operating in Poland, over which they may have direct or indirect control and whose profits go in part to the beneficiary’s account.

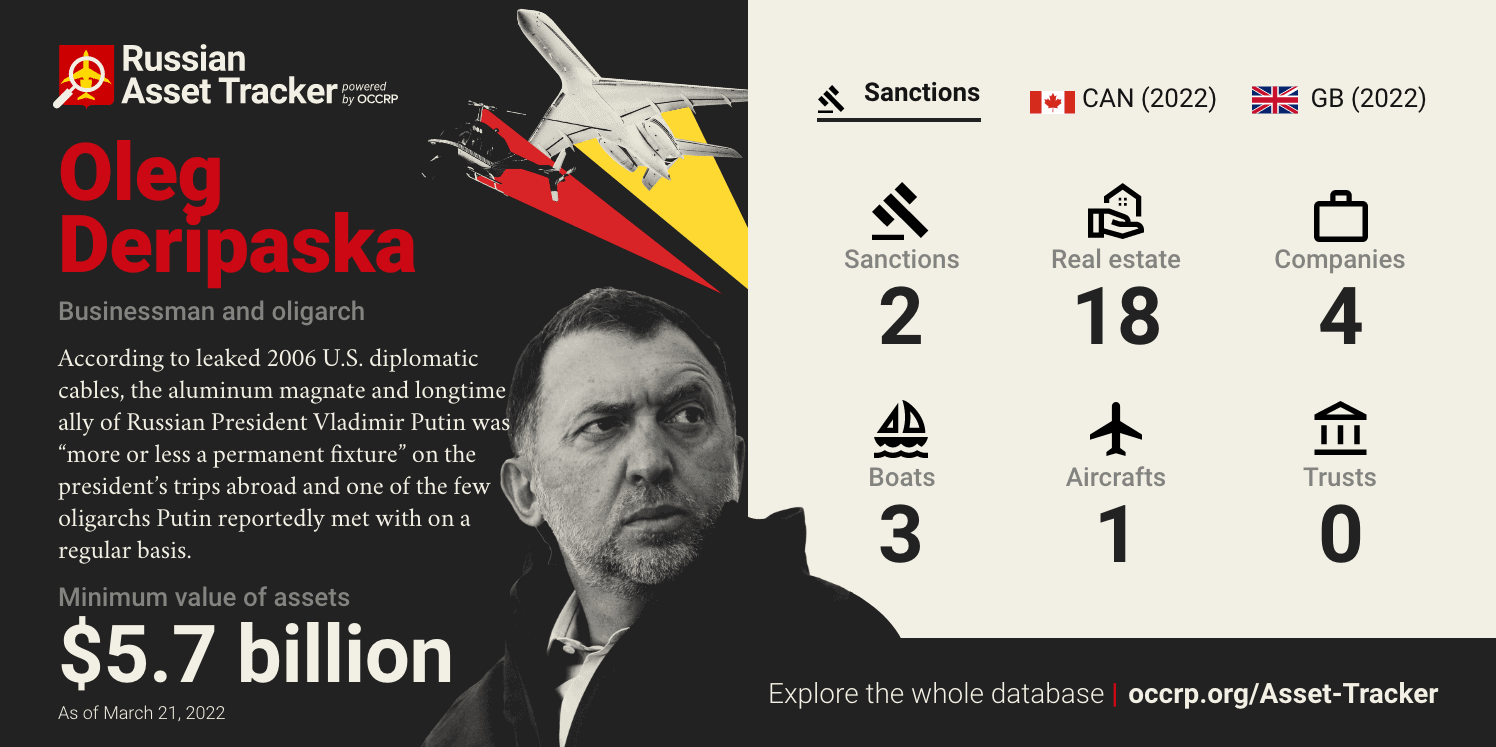

Take, for instance, the Austrian construction company Strabag, one of whose largest shareholders, through MKAO Rasperia Limited (it owns a 27.8% share), is Oleg Deripaska, a Russian oligarch. As a result, Deripaska is the ultimate beneficial owner of 31 companies operating on the Polish market in which Strabag directly or indirectly holds shares. One of them is a company that manages luxury hotels in the centre of Warsaw. But does this mean that by making a reservation at Polonia Hotel that we are putting money in Deripaska’s pocket?

There is a general rule, a simple philosophy, in business: if you own shares in a company, and that enterprise makes money, you too will make money. Therefore, we can assume that when you pay for a night’s stay in a hotel in which a company owns shares, that business will see some profit. So, if you pay 100 euros for lodging, 50 cents or less may end up in the hands of the real beneficiary, said Dr Katarzyna Witkowska, a lawyer specializing in white collar crime as well as in civil and commercial disputes who works for Crido consulting company.

Strabag has cut itself off from its Russian shareholder and is trying to deprive him of his shares in the company. It has also announced that it will not pay dividends to Rasperia, through which Deripaska holds shares in Strabag.

Things are different for the fertilizer business of Russian giant PhosAgro, which produces and sells phosphate fertilizers in a hundred countries around the world – the company itself operates in the Polish market. On 9 March 2022, the European Union placed PhosAgro manager Andrei Guryev, Jr., on the sanctions list. Shortly thereafter, Lithuania suspended the Lithuanian branch of PhosAgro’s bank accounts, freezing 2.9 million euros in funds. Guryev then resigned.

Has PhosAgro, which also operates on the Polish market through its daughter company PhosAgro Polska, experienced any consequences of the sanctions against Andrei Guriev? We tried to find out by asking this question to managers from both the Polish and Lithuanian subsidiaries and officials from the Polish General Inspector of Financial Information (GIIF) under the Ministry of Finance. The PhosAgro representatives we spoke to denied that they would face sanctions, whereas the Polish authorities did not answer, citing financial secrecy.

Financial secrecy, which forbids the GIIF from disclosing which companies’ assets in Poland have been frozen, is the refrain we heard when we asked about another company from the energy sector linked to a Russian group – this time Inter Rao. In one of its many incarnations, IRL is also present in Poland through a network of related companies. At the beginning of this chain is the Russian Inter Rao and at the end is IRL Polska. (Main shareholder of IRL Polska is Inter Rao Lietuva, then we have Rao Nordic and at the end Inter Rao with Igor Siechin as s chairman of the board of directors). The only real consequence that we unearthed was the removal of Inter Rao Lietuva from the Warsaw Stock Exchange.

Since the European Union began imposing sanctions, the Polish authorities have been pondering how to deal with assets that are present in Poland and tied to Russia through a complex network of relationships. Freeze or seize them? Ban companies from the Polish market? The latter option for, say, Austrian construction giant Strabag would mean cutting it off from a powerful market.

For weeks, we have been trying to determine what the Polish authorities are doing to prevent Russian oligarchs from operating in Poland. With no result. The last precise data about how much has been seized or frozen comes from March 24, when Deputy Finance Minister Sebastian Skuza told the Sejm that “the amount of Russian financial assets frozen in Poland so far is 160 million PLN.”

Now, after more than a month of Russia’s war in Ukraine, politicians from the ruling party PiS argue that in addition to the law that the Polish parliament passed on Thursday, which would freeze Russian-linked assets in the country, in order to effectively fight against Russian capital in Poland, it is necessary to amend the constitution.

The proposed law passed on Thursday would involve the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Administration’s keeping a special list of individuals and entities whose assets are to be frozen. Funds that will be frozen include cash, cheques, money orders, deposits placed in financial institutions or other entities, securities, bonds, stocks, and shares. The next step will be the confiscation of assets. As explained by government spokesman Piotr Müller, thanks to the proposed constitutional amendment Poland will be able to seize the assets of entities on the EU sanctions list, but also of those that “directly or indirectly support the activities of the Russian Federation or its military activities in Ukraine.”

But the road to amending the constitution is long and bumpy: it takes the approval of at least two-thirds of parliament.

Slovakia

Strabag also owns several subsidiaries in Slovakia, where it is the number one company on the construction market. Based on the findings of the Investigative Center of Ján Kuciak, since 2014 Strabag has been awarded public contracts valued at approximately 2 billion euros. In Slovakia, this construction giant builds railways, highways, and even industrial parks for major automotive producers.

This means that it is not just private money from Slovakia that eventually finds its way into the pockets of Strabag’s shareholders. They are also profiting from taxpayers’ money. There would be nothing special about that, if one of the major shareholders of this Austrian giant were not the notorious Russian oligarch, Oleg Deripaska.

Some Slovak authorities were concerned by this fact. It is not a good look for the money of Slovak taxpayers to end up in the pocket of a Russian oligarch who is sanctioned by the UK, Canada, and the US for his role as Vladimir Putin’s crony.

In mid-March, the Slovak government began working on an amendment to the Public Procurement Act, led by the Minister of Investments, Regional Development and Informatization of the Slovak Republic, and also head of one of the coalition political parties “For the people” (Za ľudí), Veronika Remišová.

On 17 March, Remišová stated that the amendment is intended to prevent Russian companies and companies with Russian owners from taking part in public tenders in Slovakia, specifically mentioning Oleg Deripaska.

“Mr Deripaska is on the European Union’s sanctions list. My personal opinion is that he should certainly have problems drawing public resources in Slovakia,” Remišová said. From that moment, the proposed amendment of the public procurement law was nicknamed “Lex Deripaska.” It has recently passed through the Slovak parliament.

However, there are two problems. First, Minister Remišová was wrong. Mr Deripaska was in fact not on the European Union’s sanctions list at the time; he found himself on it much later, on 8. april 2022. Second, she stated that Slovakia should prevent companies with owners from countries that Bratislava deems hostile to the Slovak Republic from participating in public procurements.

The wording of the amendment specifies that it applies only to companies from third countries, that is, entities registered outside of the EU. If Remišová and her ministry wanted to draft a “Lex Deripaska,” they have in fact passed a law that specifically does not target Strabag or Deripaska, as Strabag is registered in Austria, which is, of course, in the EU.

When asked about this point, the ministry’s communication department provided us with the following response indicating that the amendment was actually never meant to target a specific company or person: “The goal was to create a system for the state to have an effective tool for protecting the security interests of Slovakia and Slovak entrepreneurs. If a specific person is on the EU sanctions list, the Slovak Republic will implement these sanctions, including non-payment of monetary benefits that could, even indirectly, reach such a person. However, the legal basis must be in European law, as it [Strabag] is a European company, and not in the Slovak Public Procurement Act.”

Any changes in or a ban on the participation of European companies with Russian owners in public procurement within the EU will have to be agreed upon at the EU level. Individual member states simply cannot implement such a regulation without breaking several international treaties themselves. Therefore Slovak “lex Deripaska” does not pose any threat to Strabag. Few days ago, however, the EU put Oleg Deripaska on its sanctions list, and this might prove a bigger problem.

The Czech Republic

Strabag also has several subsidiaries in the Czech Republic, where it regularly secures state contracts and subsidies; in 2021 alone, the company signed public contracts worth 35 billion CZK (approximately 1.5 million USD). In the Czech Republic, this construction giant builds mainly roads and highways. It is also supposed to be one of the contractors to construct another metro line in Prague.

On 15 March 2022, Strabag announced in a press release that the company is terminating its “syndicate agreement in place with the UNIQA and Raiffeisen Groups and Rasperia Trading Ltd. after all efforts to acquire the Russian shares have failed. The syndicate agreement had been in effect since 2007.” Strabag has also announced that it is withdrawing from the Russian market and that it will provide financial aid to countries affected by the Russian aggression in Ukraine – namely, Poland, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, and Moldova.

Another name from Navalny’s list is Alexander Bastrykin, who from 2000 to 2008 was the owner of a Czech company called LAW Bohemia s.r.o. This means that his ownership of the company collided with him taking a public office in 2001, which is illegal in Russia. Since 2009, the owner of LAW Bohemia has been Bastrykin’s former wife, Natalia Bastrykina, whom he divorced in the 1990s.

LAW Bohemia owns two apartments in Prague. Both purchase contracts were signed by Bastrykin himself. The first apartment, located in Prague’s Troja district, is 50 square metres large with a terrace and lies on the fourth floor of an apartment complex. In 2004, the property cost 1.7 million CZK (approximately 66,000 USD); the current price is around 6 million CZK (approximately 267,000 USD).

The second apartment is in the Letnany district and is 138 square metres with a 40-metre- square terrace and two balconies. In 2007 it cost 4.8 million CZK (approximately 214,000 USD). Today, it would sell for around 11 million CZK (approximately 490,000 USD). The name of the company is still on the doorbell. The wife of a former director of the company, Igor Shutenko, owns an apartment in the same building.

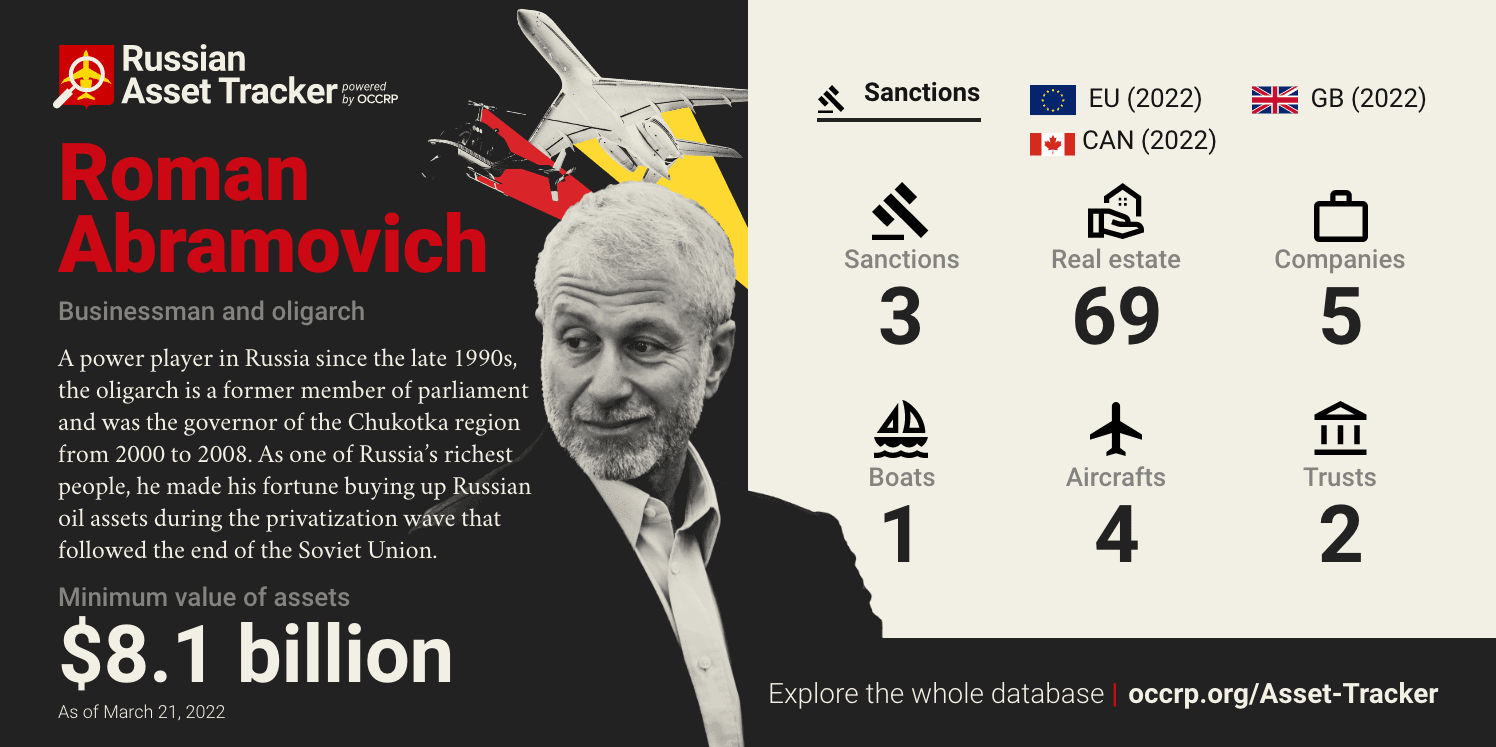

Roman Abramovich, one of the most famous Russian oligarch’s Czech connection is through a 28.6% share in Evraz, a global steel, mining, and vanadium company with operations in Russia, the US, Canada, the Czech Republic, and Kazakhstan. The Czech branch, Evraz NIKOM a.s., is a supplier of metallurgical materials to other companies that are a part of the group. The Czech subsidiary is owned by Luxembourg-based Evraz Group SA. The annual turnover of Evraz NIKOM in 2020 was 2 billion CZK (approximately 88 million USD).

At the end of March, the Czech government agreed on taking steps towards regulating which companies and individuals can be awarded public contracts, ordering the Ministry of Finance in cooperation with the Ministry of Regional Development and the Ministry of Industry and Trade to prepare a special law on sanctions resulting from the Russian attack on Ukraine. The law would target Russian and Belarussian companies and businessmen with ties to Putin’s and Lukasenko’s regimes and prevent them from participating in the public procurement process and ban them from accessing public financial support and investment incentives.

The Ministry of Finance spokesperson explained that this law has the highest priority and should soon be ready for approval.

The Czech government aims to go beyond the EU sanctions list, creating its own list that includes people and entities connected with the Russian and Belarusian regimes whose presence in the Czech Republic Prague considers to be unacceptable. Work began on such a document in the first days after the invasion. In addition to government agencies, Czech intelligence services are also involved in its preparation.

There would, however, be a problem with implementing any form of sanctions against Russia and Belarus. In 1994 and 1996 the Czech Republic signed bilateral investment agreements with both countries that protect private investments. The agreements are still valid and depriving Russian or Belarusian citizens from taking full advantage of the business environment in the Czech Republic would be in direct breach of these agreements.

The Czech government is also considering confiscating the assets of Russians and Belarusians connected to Putin and Lukashenko. This would again be in conflict with the above-mentioned investment agreements. In addition, confiscation would go beyond how the European Union as a whole is proceeding. Thus far, the bloc has only frozen the assets of Russian and Belarusian oligarchs on EU territory (in the Czech Republic, such sanctions are imposed by the Financial Analytical Office).

A sizable chunk of Russia’s wealth has been siphoned offshore by corrupt politicians and well-connected businessmen. We wanted to know where it went — so we started hunting. OCCRP and its partners trawled land records, corporate registries, and offshore leaks to come up with this database of assets belonging to key figures close to Vladimir Putin. Proving the ownership of yachts, mansions, and planes is not easy, since their owners often take pains to keep them hidden. We only included assets in this database if our researchers uncovered clear evidence of their ownership. We’ve also included assets owned by family members and known proxies of the figures we investigated. Explore what we found, and check back regularly for new additions.

Konrad Szczygieł is an investigative journalist at FRONTSTORY.PL. Previously, he was a reporter at Superwizjer TVN and OKO.Press. Since 2016, he has worked with Fundacja Reporterów (Reporters Foundation). He was shortlisted for a Grand Press award (2016, 2021) and an Andrzej Woyciechowski award (2021). He is based in Warsaw.

A Czech journalist, Zuzana Šotová has worked for the Czech Center for Investigative Journalism since 2020.

Tomáš Madleňák is a Slovak journalist who has worked for the Investigative Center of Ján Kuciak since 2020. He is based in Bratislava.