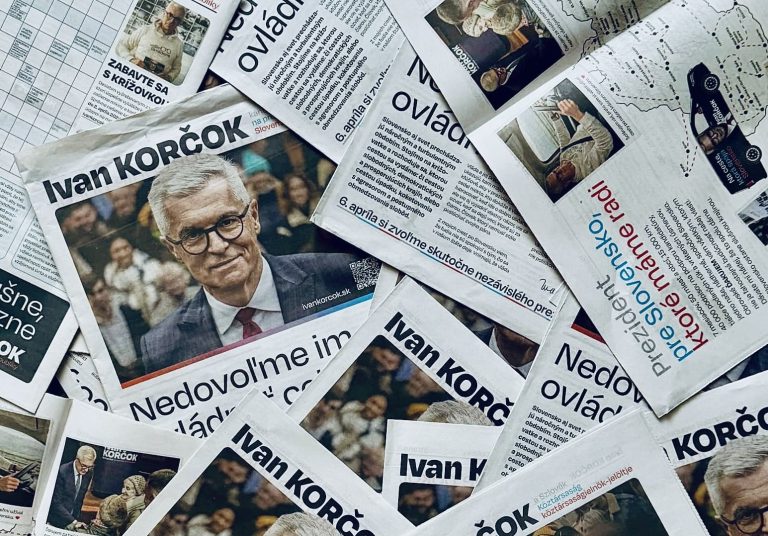

Photo: Ivan Korčok's Facebook page 2024-10-10

Photo: Ivan Korčok's Facebook page 2024-10-10

Before the spring 2024 presidential elections in Slovakia, a viral hoax claimed that opposition candidate Ivan Korčok had collaborated with the communist State Security Service (StB). An analysis revealed that the hoax was primarily spread by fake Facebook accounts, manipulating public opinion and undermining democratic processes during the elections.

A viral hoax about Slovak presidential candidate Ivan Korčok’s alleged cooperation with the communist State Security Service (StB) of Czechoslovakia was largely spread by fake Facebook accounts before the spring 2024 presidential elections, an analysis by the Investigative Center of Ján Kuciak (ICJK) reveals. Almost half of the shares and comments on the video posted at the time by Zoroslav Kollár, the main figure promoting the hoax, came from profiles displaying inauthentic behavior – fake accounts, or so-called trolls.

Fake accounts on social networks have long influenced public opinion by manipulating discussions and artificially increasing the reach of specific content. Experts say that, in doing so, they are also threatening democratic processes.

Moreover, in Slovakia, this is not the first time that hoaxes on social networks have been used in election campaigns. Just before the parliamentary elections on September 30, 2023, a deepfake hoax was spread by pro-Russian actors, alleging that the United States and independent Slovak media were attempting to rig the election. This may have been the first instance in the Western world where deepfake material was deployed in an election battle.

Fabricated documents, conspiracy theorists and fake account

The subsequent hoax smearing opposition presidential candidate Korčok – a former career diplomat and foreign minister of Slovakia between 2020 and 2022 – was also spread during a closely contested election race where, in the end, Peter Pellegrini, backed by Prime Minister Robert Fico’s ruling Smer party, emerged victorious. He secured 53 percent of the vote in the second round of the Slovak presidential election in spring 2024, becoming the country’s next president.

“We can almost certainly believe that Mr Korčok collaborated with the State Security,” said former bankruptcy lawyer and millionaire Zoroslav Kollár, convicted of corruption and accused of interfering with the independence of the judiciary, two month before the first round of the presidential election, in a YouTube video that had almost 230,000 views by September 2024.

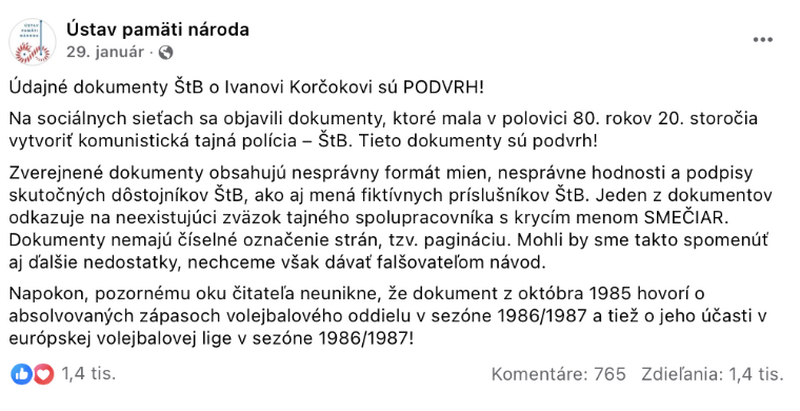

In the video, he shared fabricated documents, according to which Korčok was singled out by the communist secret service as a student and member of the university volleyball team. In the video, Kollár claimed that Korčok made contact with the StB and repeatedly denounced his teammates to the communist state police. The fake documents were signed and named by specific members of the secret service, some real, others completely fabricated. Slovakia’s Institute of Memory of the Nation (ÚPN) confirmed that some of the people who allegedly signed the fake documents were fictional people; not only did they not sign the documents, but they never even existed.

Zoroslav Kollár published the video on January 28, 2024 at 4:30pm. According to ICJK’s analysis, six minutes later, the 18-minute video was shared on Telegram by Daniel Bombic, a prominent figure in the Slovak disinformation scenet accused of extremism, dangerous stalking, defamation and dangerous electronic harassment, with several government politicians in online discussions. An hour later, the report was picked up by Mimi Šrámová, an assistant to SNS (junior coalition party) MP Ivan Ševčík.

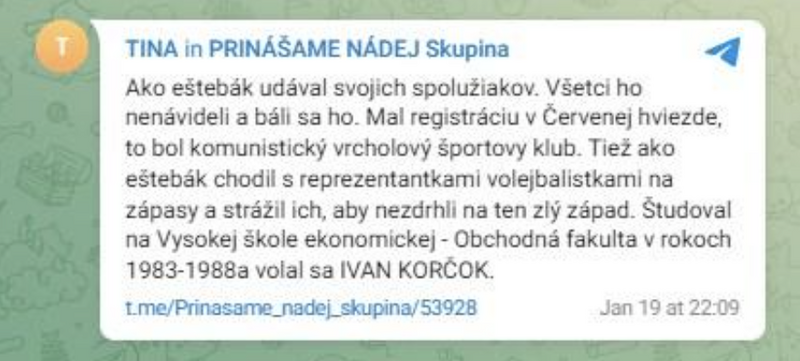

The hoax about Korčok’s (imaginary) cooperation with the StB started to spread even before it was published by Zoroslav Kollár. ICJK tracked down a post by a user named TINA from January 19 on Telegram. The false claim then also appeared in two Telegram groups. On the same day, at 9:33pm, the hoax was posted in the REŠTART SR discussion group run by Marek Šoun. At 10:09 that evening, the same content appeared in a group run by Pavol Forisch and named PRINÁŠAME NÁDEJ Skupina. At some point, the account TINA now appears on Telegram under a new name, Šipka.

Screenshot of Tina’s Telegram account post from January 19, 2024

When the misinformation was later refuted by the Institute of the Memory of the Nation (ÚPN) on its official Facebook page, a profile under the name of Tina Šipka (that, back in January, appeared in in January as Tina Bisba) responded with aggressive comments at least 18 times. But this profile also shows signs of not being what it claims to be – for example, it has a profile photo showing “Tina’s” head from behind, and no way to see how many Facebook friends she has or whether she has any friends at all. It was the most active profile in the comments under the ÚPN post.

But though the hoax was first spread by anonymous Telegram accounts, it was not until Zoroslav Kollár’s video, posted a week later, that it went viral. Kollár first gained popularity on social networks with pre-election videos attacking politicians like Boris Kollár (no relation), Jan Budaj, Richard Sulík and former special prosecutor Daniel Lipšic.

It was Kollár’s video about Korčok and the StB, which bears the hallmarks of disinformation (i.e. false or manipulated information deliberately disseminated to mislead and harm), that spread like wildfire and resulted in the massive spread on social networks of a story that was not true. It all happened in the run-up to the presidential elections.

Fake accounts have seriously contributed to the spread of misinformation

Fake accounts, or trolls, that are not run by the people they purport to be and amplify and further disseminate misleading content, also stepped in and spread Kollár’s video. Fake news about the candidate’s alleged cooperation with the StB quickly spread through large disinformation Facebook groups.

“Trolling undoubtedly influences voter behavior,” said disinformation expert Peter Jančárik. Matej Kandrík of the think-tank Adapt added that trolls can shift public opinion: “If we are talking about systematic and coordinated information influence campaigns, they can create a bending effect on public opinion and attitudes of significant parts of society.”

According to Jakub Šuster of elv.ai, a platform dedicated to moderating toxic comments on social networks, trolling makes it appear to ordinary users that the views of trolls are widely accepted. “They often repeat false or misleading information, and they may also misuse humor or irony to make their statements seem innocuous on the surface. In short, they generally use personal attacks, distort arguments and refuse to engage in constructive debate, or even engage in it at all,” Šuster concluded.

Zoroslav Kollár published several videos about Ivan Korčok in the election campaign. He helped the viral spread of the hoax about the StB. (Screenshot)

ICJK reporters collected and analyzed the data available on the individual posts through which the false claim about Ivan Korčok was spread. They found that the video in question and the alleged StB documents referred to by Zoroslav Kollár were shared at least 9,500 times on Facebook.

According to ICJK’s findings, many of the shares and interactions related to the video and documents were not from authentic social media users, but rather were from fake accounts. Kollár’s original YouTube video serves as an example: While it was the most viral of all the posts, with more than 2,600 shares in total, it was shared only 23 times to public Facebook groups. Of these 23 public shares, we identified 58 interactions, including shares, reshares, and comments. Of these interactions, only 27 accounts showed clear signs of authentic behavior, suggesting a high level of involvement of inauthentic profiles (again, profiles that are not run by the person presented as being behind the account) in spreading misinformation.

The most successful Facebook post about the hoax was published on January 28 by the profile “Ranné správy – Marek Šoun.” It was shared by 2,600 accounts and received 299 comments. When we analyzed this post in September 2024, 194 accounts had posted still visible comments on the post, with some accounts commenting multiple times. Of the nearly two hundred accounts, we identified as many as 74 profiles, or about 40 percent, that could most likely be labeled as fake accounts.

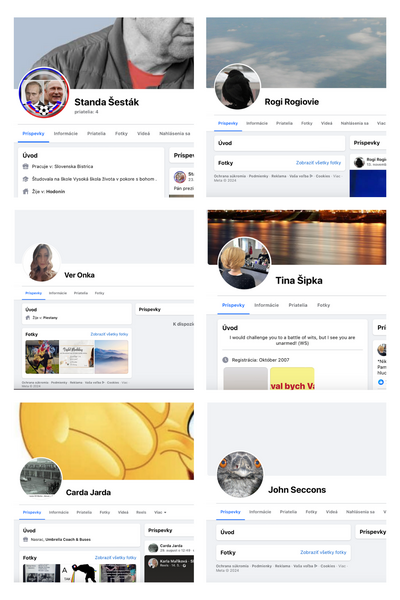

A collage of screenshots of Facebook user profiles who commented on the most viral Facebook post about the Korčok hoax

The hoax was also shared by Facebook profiles associated with Prime Minister Robert Fico’s party, Smer. These included the party’s page for the city of Bratislava and the Smer page for Pezinok.

ICJK conducted its analysis using the Crowdtangle tool until it was shut down by Meta in mid-August 2024. Individual shares on private profiles cannot be analyzed in an aggregated way on Facebook, as the platform does not provide such data to researchers either. Additionally, when a private account shares misinformation, it can only reach their pre-existing network of followers, so we focused on public groups.

How fake accounts behave on Facebook

The fact that the documents about Ivan Korčok’s alleged cooperation with the StB were fake and showed signs of forgery has been confirmed by both ÚPN and the Czech Archive of Security Forces (ABS). These untruths have also been refuted by independent fact-checkers of AFP and Demagog.sk, both of which have pointed out that the documents contain inconsistencies in the names, ranks and signatures of StB officers, as well as in code names and file markings, and that they use a format different from the StB files of the time.

We already mentioned that the profile for Tina Šipka exhibits inauthentic behavior and was the most active account in spreading misinformation under the ÚPN post debunking the viral video. But Šipek’s was not the only one: ICJK analyzed the publicly available comments on the Institute’s profile and revealed that 80 of the 239 profiles that commented on the Institute’s post showed clear signs of being fake accounts. Nearly 100 people responded to comments left by Tina Šipkas under the ÚPN status, often suspecting it was a fake profile intended to stir up aggressive debate. Some accused whoever was behind the account of spreading misinformation.

However, it should be stressed that it was not possible to review all comments. According to its spokesperson, Simon Borsig, ÚPN follows Facebook’s community standards, which emphasize the maintenance of respectful and constructive discussion, and therefore deletes vulgar comments. “We ban hate speech, vulgarities, spam and other forms of inappropriate behavior. If any comments were deleted, it was because they contradicted these principles,” Borsig said, adding that the same procedure was followed in the discussion under the post refuting Ivan Korčok’s cooperation with the StB and that, today, per Facebook’s rules, they no longer have access to the deleted comments.

“Trolling is just one of the many tools used by manipulative information campaigns or operations,” explained Matej Kandrík, head of the think tank Adapt, which focuses on defense and security policy. He argues that sharing posts and commenting through fake accounts is a tool to radicalize voters according to their political affiliation. Fake accounts thus play a key role in polarizing society and intensifying political opinion on social media.

An example is the disinformation campaign by Russian trolls to influence this year’s European Parliament elections. According to data leaked from the Russian IT organization Social Design Agency, obtained by the Estonian portal Delfi and the German media Süddeutsche Zeitung, NDR and WDR, a Russian campaign was aimed at manipulating public opinion, spreading fake news and supporting radical right-wing parties as well as anti-EU entities, all while undermining pro-European governments.

An international investigation showed that the so-called Russian digital army created 33.9 million comments and published almost 40,000 posts on social networks in the first four months of 2024 alone. Russian coordinated online propaganda has destabilized the political environment in Europe through fake accounts.

According to elv.ai, a platform dedicated to moderating toxic comments on social networks, people can identify inauthentic, trollish, accounts on social networks by noticing that it has, for example, a suspicious name or profile picture, or if the account doesn’t list friends. “While it is true that more and more people have no problem trolling under their real identity,” said Jakub Šuster, founder of the platform, the aim of trolls is to distract from substantive discussion, which often turns into a contentless and vulgar exchange of opinions.

The accounts that helped share the Ivan Korčok hoax were characterized by similar inauthentic behavior – they often used fake names, fake profile photos, had few friends and only shared certain types of content. Examples of such accounts include Eugen Kotek and Elena EL, who, less than an hour after posting the video of Zoroslav Kollár on YouTube, shared content to several groups such as Volíme Harabina, Celoslovenský občiansky snem – Pán Občan, Nahlas či Slovenský patriot, which often feature disinformation content.

Screenshot of the “Eugen Kotek” fake account’s Facebook profile

Eugen Kotek’s profile shows clear signs of inauthenticity. The account has only seven friends; his profile photo is a picture of a film character; and the cover photo is completely missing. He has posted only three photos on his profile: one with cables and two with insects. Most of his posts promote pro-Russian narratives.

We also spotted Eugen Kotek’s profile in the Volíme Harabina group, where he exhibited the same patterns of behavior. The profile was created in 2019, but he only started actively contributing to this group in 2021. Since then, he has shared more than 100 posts in spurts. For example, he contributed heavily from July to September 2021, and later in December of that year. Between January and July 2022, he was almost continuously active before going on a posting hiatus for a year. Then, from June 2023 to the end of the year, we again see increased profile activity.

A profile with the name Elena EL, which also spread Kollár’s video about Ivan Korčok in several public Facebook groups with a wide reach, uses a photo of a woman’s face as its avatar.

Screenshot of the “Elena EL” fake account’s Facebook profile

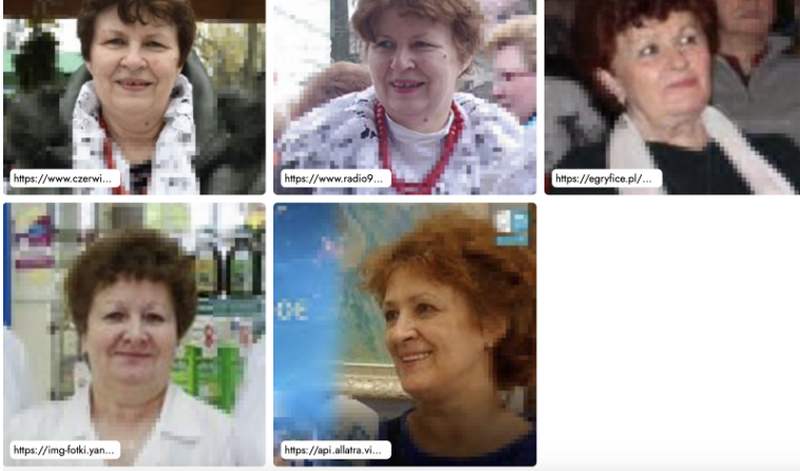

But who was the woman? ICJK reporters, using a reverse search of the profile photo, found that the photo of the woman likely belonged to a real person, but all search results led us to Polish websites. Elena EL’s profile, however, is presented as Slovak, suggesting that it may be a fake account used to spread misinformation.

“Elena” has a picture of a mushroom as her cover photo and, in addition, she has only posted one other photo of her alleged children in a garden. Her number of friends is not publicly available; there is no way to friend request her; and there are no posts that she can be seen to have shared.

“As well as flooding the online space with misinformation, conspiratorial, offensive or misguided comments, fake accounts also give the impression of the masses. In discussions, they create a false image that their ‘opinion’ is the majority one. The problem with trolls is that they also poison discussion threads with their posts, and a decent person who would otherwise join the discussion changes his mind,” said Peter Jančárik, an expert on misinformation.

According to Jakub Šuster from elv.ai, the hoax about Ivan Korčok and the StB was a textbook example of the spread of disinformation, which managed to travel much faster in society precisely because of the “fantastic” nature of its content. “Fact checkers took far too long to check the whole thing and come up with the true version, which cannot be blamed on them. In the meantime, the hoax about Korčok as an agent of the StB had already gathered strength. Almost immediately, various hateful pictures on this theme began to circulate in the comments, and to a large extent also photographs of his non-existent identity card,” he said.

Screenshot of the results of the Pimeyes reverse image search tool – suggesting that “Elena EL” uses the face of a Polish woman

Based on his own experience of managing comments, Šuster sees trolling as one of the threats to trust in democracy, especially in countries where trust is already low. “This can further manifest itself, for example, in elections, where people in this country may prefer rather radical parties, which they either vote for out of fear or as a form of protest against the established system,” Šuster added.

How did the Korčok hoax affect the pre-election atmosphere?

The hoax about Ivan Korčok’s alleged cooperation with the communist State Security Service was one of the most viral and successful pieces of disinformation in the presidential campaign. In February, The Central European Digital Media Observatory investigated the spread of disinformation in Slovakia.

According to the results of the survey, up to half of the respondents had encountered the hoax, while about a third of respondents believed it.

“We know from research that social media users often don’t even click on the article or post being discussed, but are first interested in what people in the comments think about the topic. Thus, comments contribute to framing social topics. In doing so, the people who write them may not be real and may not base their opinions on reality or facts. They simply flood and poison the social discourse with their narratives,” said Peter Jančárik.

According to Šuster, in addition to the traditional dissemination of misinformation, troll farms try to distort public opinion by boosting their posts’ engagement. “In this way, it can appear to ordinary users that it is the opinions of trolls that are widely accepted, which can, on the one hand, induce fear in them or, in the worst case, make them doubt their own views or values,” said Šuster.

The article was originally published on ICJK.sk.

Subscribe to “Goulash”, our newsletter with original scoops and the best investigative journalism from Central Europe, written by Szabolcs Panyi. Get it in your inbox every second Thursday!

Karolína Kiripolská is a Slovak journalist working at the Investigative Center of Jan Kuciak (ICJK). Previously, she worked at the Slovak independent outlet Denník N, where she began as a reporter and later served as a web editor. Karolína has experience in fact-checking, having worked for US company LeadStories, verifying information for platforms like TikTok and Meta.