Cover photo: ICJK 2024-08-22

Cover photo: ICJK 2024-08-22

The European Union’s Green Deal has set an ambitious goal of becoming the world’s first climate-neutral continent by 2050. The EU’s actions are aimed at using renewable energy sources, eliminating dependence on fossil fuels and reducing greenhouse gas emissions. Road transport accounts for a quarter of emissions, and only by reducing them by 90 percent can the EU achieve carbon neutrality. One of the solutions was intended to be the biofuels that we all refuel our cars with. Thanks to European subsidies, a billion-euro industry has built up around them. The oil refineries have got involved and are trying to repaint themselves green. Meanwhile, the EU is changing its stance and no longer considers first-generation biofuels, made mainly from maize and rapeseed, to be an environmentally friendly solution. However, they still dominate in Slovakia. Their producers and supporters also play an important role in the information space, defending their production and criticizing the EU’s new approaches.

If you type the keyword biofuels in Slovak into a search engine, an explanation from Wikipedia appears on the first page of results, but a large part of the links point to texts published by biofuel producers.

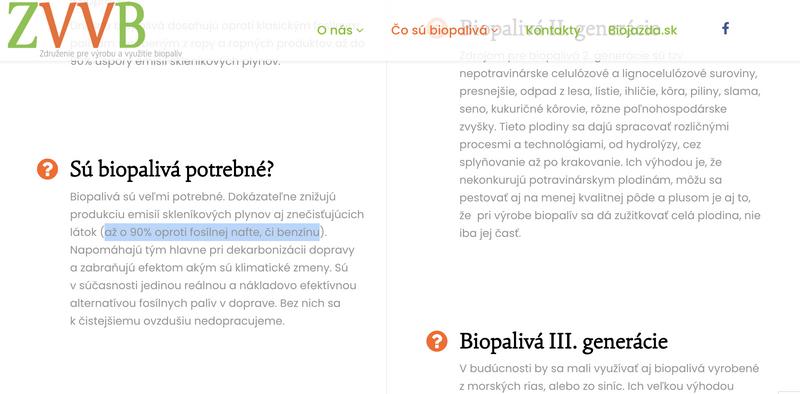

“Our Slovak biofuel sector produces liquid ‘first generation’ biofuels made from corn, sunflower and rapeseed…. Currently, the development of ‘second generation’ biofuel technologies is underway, which are produced from cellulose, agricultural residues or even waste. However, second-generation biofuels are not yet commercially produced because they are too expensive. Laboratories are also beginning to investigate ‘third generation’ biofuels, which could be produced from algae. However, we are probably still decades away from the introduction of 2nd and 3rd generation biofuels, as 1st generation liquid biofuels alone have taken almost 80 years to research and commercialize,” reads the All About Biofuels website, which came third in the search engine. It is only from the small letters in the header of the page that the reader learns that it is run by the Association for the Production and Use of Biofuels (ZVVB).

It is not an independent organization. Its representatives include Slovak biofuel producers primarily from around the strongest Central European biofuel group Envien, linked to Slovak businessman Ján Sabol. The group’s strength is underlined by the fact that it is the exclusive supplier of biofuels to Hungarian refining giant MOL and its Slovak refinery Slovnaft, and they also jointly run several companies.

“We will not impose on anyone the idea that biofuels are eco, the best, and that they will save the world,” the association says on its All About Biofuels page. In its own words, ZVVB wants to offer the widest possible spectrum of objective information and “seriously discuss biofuels, their advantages and disadvantages, myths and truths”. However, in presentations and media appearances, representatives of the biofuels sector mainly defend their main product – first-generation biofuels. In 2023, these accounted for almost 94 per cent of all biofuels on the Slovak market, while the European Union has been moving away from them since 2015. “As far as the shift away from first-generation biofuels is concerned, this is basically a trend that Europe is already moving towards today,” explains energy analyst Radovan Potočár. But he adds that change takes time. “The solutions that are currently available as alternatives would not be able to cover the shortfall of first-generation biofuels from one day to the next, but it is certainly right that, even if at the cost of higher costs, the next trend will be towards more advanced biofuels,” the expert thinks.

The presentations by biofuel producers lack consideration of studies or data that show, for example, the environmental pollution caused by biofuels. Nor do we read about studies that contradict the claim that biofuels reduce emissions. We also do not learn that, according to the Slovak Hydrometeorological Institute (SHMÚ), which is responsible for monitoring, biofuels also contribute to pollutants in transport. Slovak biofuel producers also reject criticism from the European Union and experts who see the production of primary biofuels as making food more expensive and taking up quality land. They speak of the advantages and irreplaceability of bio-ingredients in fuels.

The topic of biofuels is not easy to navigate. There is little comprehensive information on their advantages and disadvantages from independent Slovak sources. We cannot find much of it on the websites of the responsible Slovak ministries or on social networks. According to Meta’s analytical tool, in the last 12 months the keywords biofuel, biodiesel or bioethanol have appeared in only 72 public posts in the Slovak language on Facebook. The analytical tool Gerulata, which examines not only the most popular social network but also others such as Telegram or web articles, found 154 posts.

Meanwhile, the biofuel debate in Europe is taking place on several levels. For example, European auditors recently found that “the sustainability of biofuels is overestimated”. They also pointed out that ‘biofuel feedstocks can damage ecosystems and reduce biodiversity, soil and water quality, and therefore raise ethical questions about the relative priorities of fuels and food’. We also asked the relevant ministries – economy and environment – about the debate in Slovakia. However, they did not respond to our request for comment.

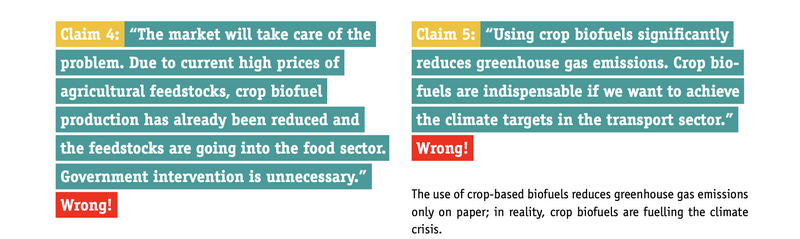

In 2022, Transport & Environment, an international NGO promoting sustainable transport in Europe, highlighted the efforts of biofuel producers to dominate the public debate. According to the organization, “crop-based biofuels have been criticized for many years because their production competes with growing crops for food”. This is one of the reasons why several European countries are considering restricting the use of crop-based biofuels. Sustainable transport advocates have also claimed that the biofuel industry is lobbying against efforts to restrict the use of crop-based biofuels. The “myths of the biofuel lobby,” according to them, aim to encourage the continued use of plant-based biofuels.

It is important to add that biofuel production is a billion-euro industry and owes its existence to the European Union. It came into being thanks to EU regulations, financial support and subsidies in order to make transport greener. If it had not been for the obligation on oil companies to blend biofuels into fossil fuels years ago, it would not be worth producing them today. According to Statista, the European biofuels production market was worth around €17 billion in 2023. The financial turnover of the Slovak biofuel industry was around €360 million in 2021, according to the latest data.

We were also interested in the views of Slovak biofuel producers on how they view the public debate in the EU or their communication. We asked why the image they create around biofuels and the EU’s arguments are so fundamentally different. However, representatives of the dominant player Envien and its affiliate ZVVB did not respond to our questions. We did not agree to their PR representative’s condition to publish all the questions and answers as one continuous text without the possibility to put them in context.

Part of the debunked claims of the ‘biofuel lobby’.

Slovakia must resolve the contradiction between achieving the EU’s green goals on the one hand, and their conservative adherence to the old methods – i.e. the compulsory blending of first-generation biofuels into fuels. Also, what we have found suggests that such a public debate is almost non-existent in Slovakia – yet it is very much alive internationally.

Oldřich Sklenář, an analyst at the Prague-based Association for International Affairs (AMO), sees both advantages and disadvantages of biofuels, pointing out that the key is what type of biofuels we are talking about. “The big advantage of biofuels is that they are actually compatible with the existing infrastructure,” he explains. He also adds that one of the advantages is that the waste from biofuel production can be used as animal feed, which is another important source of income for farmers. “At the same time, however, we have to ask to what extent biofuels fulfill their primary function, which should be to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.” The energy balance (i.e. emissions savings) of the process is questionable to say the least, he said. “It may be slightly better, but not significantly so,” he adds.

Energy analyst Radovan Potočár sees biofuels as a solution “that is already established. It is not something new that needs to be introduced. Unlike other technologies such as electromobility”. He adds, however, that although there is serious talk in some countries of banning first-generation biofuels, this is not possible overnight.

AMO’s Sklenař believes that the production of liquid biofuels generally makes no sense. “When you compare the overall societal costs and benefits, it really doesn’t make sense. It does make sense for those doing business in this area, but it doesn’t fulfill the primary function, which is to reduce environmental impacts.” However, he adds that, in the past, investment has created and set up the system, and there is existing capacity. “So now it’s more of a question for discussion, what do we do about it?”

Are biofuels environmentally friendly?

The most important question when it comes to biofuels is the most basic one. Is it really an environmentally friendly alternative that is also sustainable? If we wanted to find a quick and easy answer to this question, the keyword biofuel would not help us. The search results are often contradictory and clearly differ depending on whether those are by manufacturers, the European Union, or biofuel critics.

The biggest question marks are with the first-generation “old” biofuels, from which the European Union is retreating, but Slovakia still relies on them to a large extent. Concerns have grown over the years that they raise food prices and pollute the environment as much as fossil fuels.

Several studies have questioned whether biofuels really meet the objective of reducing emissions. According to a 2017 analysis by the UK’s Royal Academy of Engineering (which was initiated by the British government), some biofuels, such as diesel made from food crops, have produced more emissions than the fossil fuels they were meant to replace. The report also said that increasing biofuel production should instead make more use of waste, such as used cooking oil and wood – which is also in line with EU efforts.

A more recent analysis from Emission Analytics also claims that biofuels “lead to very little change in exhaust emissions”. Their measurements for different types of fuels also showed that no universally valid savings can be claimed. For E10 petrol, the company’s 2020 analysis claimed only minimal reductions in CO2 emissions. At the same time, nitrogen oxide (NOx) emissions increased significantly. This has also been highlighted by the Financial Policy Institute of the Slovak Ministry of Finance, which has also drawn attention to the potential threat to biodiversity and the economic risk of the impact on food prices. We also wondered whether the ministries had taken this previous study into account when assessing biofuels. Neither the Ministry of Economy nor the Ministry of the Environment had responded to our questions by the deadline. An information article from the Slovak Science and Technology Information Centre also states that biodiesel is more harmful than conventional diesel because it “produces more carbon dioxide or carbon monoxide when burned”.

Slovak biofuel producers, however, see the situation differently. They say they rely on crops that absorb carbon dioxide for production. “Biofuels achieve 60-90% greenhouse gas savings compared to diesel and petrol over their entire life cycle,” Peter Kostík, CEO of Envien Group, told the SME newspaper. The claim of 90 percent savings also appears on the website of the association of biofuel producers. They claim that biofuels “demonstrably reduce the production of greenhouse gas emissions and pollutants (by up to 90% compared to fossil diesel or petrol)”. However, they do not cite any source.

Source: ZVVB

We were also curious about the positions of the Envien Group and the Association for the Production and Use of Biofuels. We asked, for example, what data and measurements they work with to determine the advantages and disadvantages of (first-generation) biofuels. We also asked them why some of the claims on their website do not align with the views of certain experts. They did not respond to our questions.

The European Commission, according to the auditors’ reports, already “recognized in 2014 that food-based biofuels have a limited role to play in decarbonising the transport sector”.

Transport & Environment also draws attention to an important aspect. Although official figures suggest that crop-based biofuels help reduce greenhouse gas emissions, “a very important factor is missing from these calculations”, namely taking into account the amount of land used to grow the crops. According to their reasoning, based on data from Germany, the demand for agricultural land associated with crop biofuels is leading to an expansion into previously uncultivated areas. “Reserving huge areas of land for biofuel production essentially means that less land is available for natural ecosystems to store carbon,” causing enormous damage to the climate.

In Slovakia, both emissions and biofuel savings are controlled by the SHMÚ, but the state only exercises this control, so to speak, from the table. And whether the chain from the farmer to the biofuel is sustainable and environmentally friendly “is checked by professionally competent persons, i.e. certified accredited bodies that are authorized to do so. We check the documents. That is to say, whether all the documentation has been carried out in accordance with the law and whether all the supporting documents have been handed over in order to make this reporting possible and transparent. So we do not go to the subjects, we do not go to the fields,” explains Janka Szemesová, Head of the Emissions and Biofuels Department of the SHMÚ.

Biofuels and expensive food

The European Commission justifies its objections to first-generation biofuels mainly on the grounds of indirect land use change (ILUC). According to the EU, if meadows or farmland where food and feed were grown are converted into land associated with biofuel production, the additional emissions, and therefore the sustainability of biofuels as a renewable energy source, are worsened.

In 2012, the European Commission therefore proposed to restrict first-generation biofuels and promote advanced biofuels. It set limits for biofuels produced from food or feed crops. For Slovakia, this was set by law at 6 percent.

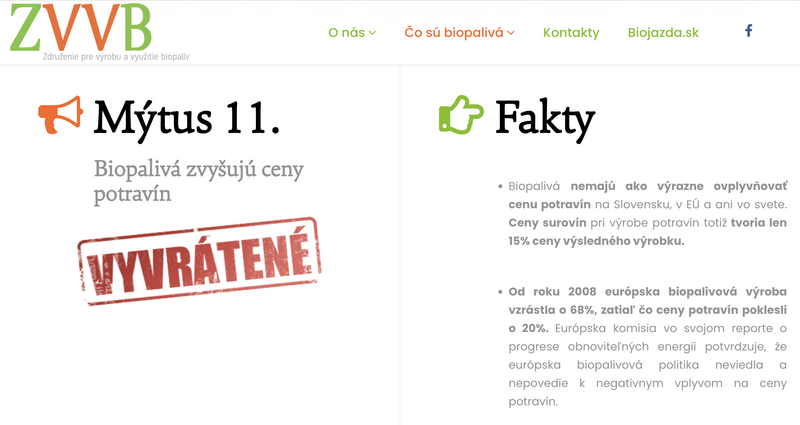

The EU’s approach has been criticized by ZVVB. n 2013, for example, they described it as a myth that “biofuels steal land from food crops and make them more expensive”. They claimed that “the reduction in the production and consumption of first-generation biofuels is not good for the Slovak or European agricultural sector” and that “land that would otherwise lie unused is being used to grow energy crops”. However, rapeseed, which is a key raw material for the production of MERO, or biodiesel, is grown mainly in the south of Slovakia. These are the most valuable agricultural areas in the country, where the land has been intensively used for agriculture for a long time.

Source: ZVVB

The Envien group themselves have in the past stated that “in accordance with the sowing practice, rapeseed is sown on the same area at the earliest once every 3-4 years”. They also claimed that rapeseed is an effective precrop for grain, for example. Even the data from the statistical office does not indicate that the introduction of rape has significantly increased the area of not utilised agricultural land.

The European Commission also proposed back in July 2016 that food-based biofuels should be phased out and replaced with “more advanced biofuels” that do not compete with food crops. This highlighted another contentious food-related issue in the context of biofuel production – the availability of food. Again, according to a 2017 article by the Centre for Scientific and Technical Information, it takes up to 2,500 liters of water to produce one liter of biofuel. In addition, the amount of grain needed to fill the tank of a larger sports car with ethanol is equal to the amount of food one person consumes in an entire year. “Last but not least, the production of biofuels also requires a large amount of land,” states the article on the disadvantages of biofuels.

Critics of biofuels have argued for many years that their production competes with food production. That is to say, that the technical plants used to produce biofuels take up good cultivable land and also that they contribute to rising food prices, according to Dusan Drabik, an agricultural economics expert. That first-generation biofuel policies were driving up prices was also claimed by another 2017 study commissioned by environmental organizations.This involved a review of 100 economic modeling studies on the impact of increased demand for biofuels produced from food crops on food prices. However, this argument is vigorously rejected by the biofuels industry. At the time, the conclusions of that study were contradicted by data from the European Commission, which found the impact of ethanol in this regard to be “negligible”.

In 2019, Slovakia and seven other EU member states received a warning from the European Commission related to sustainable biofuels. According to the Commission, Slovakia has not fully transposed EU rules that strengthen the sustainability of biofuels. These were also supposed to ensure a switch to advanced biofuels produced from materials such as waste or algae. Meanwhile, an amendment to the law on these changes was already signed by the Slovak president in 2017.

The year 2021 brought significant progress with regard to advanced biofuels in the country. Since then, there has been a mandatory blending of advanced biofuels into fuel. The mandatory percentage is currently 0.65. It will be gradually increased to a level of 2.1 percent by 2030. An important difference with first-generation biofuels is that these percentages double count towards the overall targets.

Back to rapeseed again

We have already pointed out in a previous text that rapeseed cultivation is closely linked to biofuels. This is a controversial subject that is raised every year by politicians, regardless of party affiliation, when vast swathes of fields are covered in the unmissable yellow flowers of rapeseed.

The image of rapeseed is also perceived sensitively by biofuel producers. It is one of the main crops used for the production of biofuels, namely biodiesel. Biofuel producers are hampered by the criticism of growing rapeseed in monoculture, i.e. in large swathes. Even the Ministry of the Environment states that large swathes of monocultures of rapeseed are extremely problematic in terms of their impact on the state of nature and the countryside.

The Biofuels Association argues that rapeseed is not grown in monoculture because it “means growing the same crop on the same plot of land for several years in a row”. The word monoculture can have several meanings – it can mean growing the same crop on the same plot of land for several years, or it can mean growing a single crop over a large area. And, according to experts, the problem is not only the area but also the ecologically problematic use of chemical sprays. According to MEP and ecologist Michal Wiezik, it is a game with words. “They claim that there can be several crops in one sowing, so it’s not a monoculture…. the time when the rape is growing there, it’s the only plant growing there. So we don’t have to use agricultural terminology, we can use ecological terminology and from that ecological point of view it is a pure monoculture,” he explains.

Source: ICJK

As we have written in the past, one of the advocates of rapeseed in the country is the Slovak Chamber of Agriculture and Food (the direct member of the chamber is also Enagro, a company belonging to the Envien group). According to the Chamber, Slovakia is not a country where a lot of rapeseed is grown compared to some other countries, despite the fact that it is located in the so-called rapeseed area. They base their claim on absolute acreages.

However, according to Dr Dusan Drabik, an expert in agricultural economics, it is meaningless to compare absolute areas – it is more logical to compare the proportional representation of rapeseed. In this respect, Slovakia ranks in the top five in the EU.

Enlightenment in the hands of biofuellers

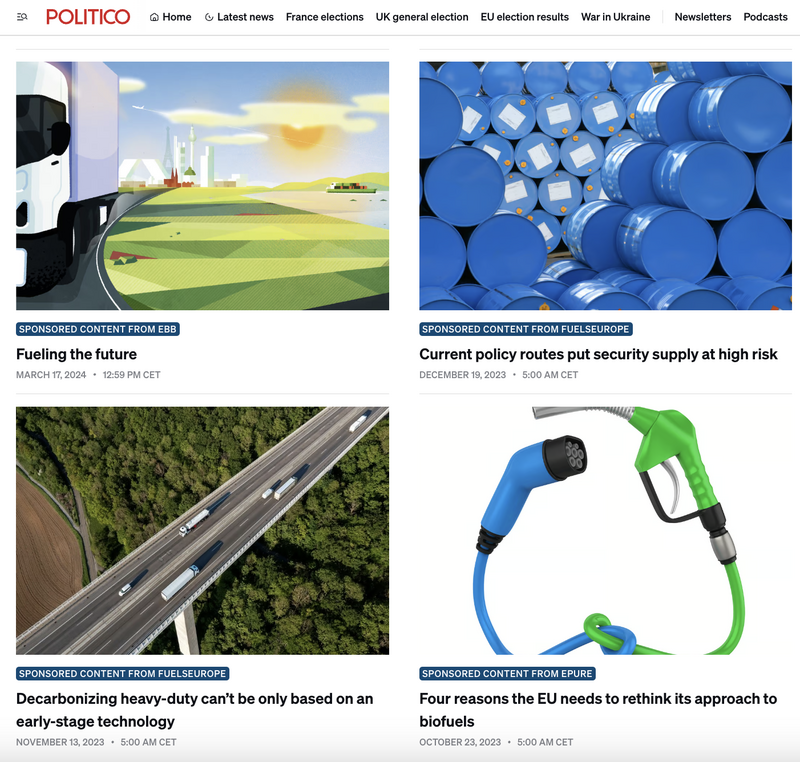

There are several organizations and lobby groups in the EU protecting the interests of biofuel producers. They try to promote their positions, for example through paid advertising or by organizing expert debates. Paid content from these organizations can also be found on the websites of established media such as Politico and EurActiv.

For example, ePURE presents itself as the “united voice of the European renewable ethanol industry”. In its own words, it seeks to represent the interests of the biofuels industry to the EU institutions, industry stakeholders, the media and the general public. Enviral, belonging to the company group of Slovak businessman Ján Sabol, is also a member of this organization.

The Slovak Association for the Production and Use of Biofuels (ZVVB) has existed for a quarter of a century. According to its description, it seeks, among other things, to spread education in the field of biofuels. The organization also deals with “myths and facts” about biofuels and operates a website “All about biofuels” (which has not been active in recent years). However, one would have to look for a long time on these platforms for materials about the disadvantages of biofuels.

Source: Politico

The producers’ association also presents its positions in the media. Several texts have also been written in cooperation with the Envien Group or its subsidiaries. For example, the association criticized the amendment to the Renewable Energy Sources Promotion Act, which also made it compulsory to blend second-generation biofuels into fuels. They described it as counterproductive. In 2022, they also argued that “biofuels are not the cause of rising food prices”. They were also critical of the European Union’s policy changes on first-generation biofuels. According to the then-chairman of the ZVVB, Róbert Spišák (today an ultimate beneficiary owner of the Envien Group), “influencing the European Commission’s decision-making on biofuel targets often happens through the creation of so-called biofuel myths”.

The association has strong links to the Envien group but also to other companies in the portfolio of Ján Sabol. It was founded by Róbert Spišák, chairman of the Envien Group. Peter Kostík, CEO of the Envien Group, is among the statutory members. The chairwoman of the association’s executive board is currently Diana Štrofová, director of external relations of Sabol’s another corporation, AZC Group. Other names on the board also figure or have figured in Ján Sabol’s companies.

We were interested to know whether, apart from Envien or its subsidiaries, there are other Slovak biofuel producers in the association at all. However, we did not receive an answer to this question either.

A greener oil industry?

Fossil fuel producers are among the planet’s biggest polluters. The pressure to reduce emissions is growing. That’s why terms like carbon neutrality, sustainability or green transformation are entering the vocabulary of the oil giants. They are therefore trying to transform their image from polluters to a green one.

In Central Europe, biofuels in particular are being touted as a way to achieve green goals. For example, Hungarian oil and gas giant MOL, which also owns the Slovak refinery Slovnaft, has set itself the target of achieving net zero CO2 emissions by 2050 in line with EU targets. This includes expanding its biofuels portfolio. These biofuels are produced from both used cooking oil and animal fats.

MOL got directly involved in the biofuel business years ago. This was preceded by a tender for the supply of biofuels to MOL, which was won by companies from the Envien group. Currently, both MOL and Slovnaft appear as minority shareholders in companies belonging to Ján Sabol’s Envien group. Slovnaft owns 25 percent in Leopoldov-based Meroco plant, while MOL has 25 percent in a subsidiary in Komárom, Hungary. These are plants for the production of biodiesel components. This symbiosis has been described by MOL in the past as “mutually beneficial“.

Based on SHMÚ data, the biggest polluters in the Slovak chemical industry are the Bratislava oil refinery of Slovnaft and the companies Enviral and Meroco belonging to the Envien group. The SHMÚ states that no significant decline is expected in emissions in this sector. “The biggest reductions in this sector could be due to a reduction in production or fuel consumption by cars and trucks, or a reduction in the consumption of artificial fertilizers in agriculture,” the institute thinks.

In the Green Deal, the European Union set itself the ambitious goal of becoming the world’s first climate-neutral continent by 2050. To achieve this, it aims to use renewable energies, which it expects to reduce greenhouse gas emissions but also reduce dependence on fossil fuel markets (including Russia’s).

According to the latest Eurostat data, all biofuels together account for more than 89 per cent of renewable energy sources in EU transport. With the first-generation ones having the main share, more than half. The data also show that the EU limits on the volumes of biofuels based on agricultural crops have been exceeded.

In the case of Slovakia, the country is still heavily relying on first-generation biofuels. According to the Ministry of Economy, all blended biocomponents in Slovakia up to 2021 were first-generation. Even in the following years, the situation has not changed significantly. Last year, first-generation biofuels still accounted for 93.9 per cent of all biofuels placed on the Slovak market.

The article was written as part of the Bertha Challenge 2024 project dedicated to tackling environmental disinformation. The Slovak version of this article was published on icjk.sk

The article was written as part of the Bertha Challenge 2024 project dedicated to tackling environmental disinformation. The Slovak version of this article was published on icjk.sk

Karin Kőváry Sólymos is a Slovak journalist at the Investigative Center of Ján Kuciak. Previously, she was an editor and presenter at the Hungarian channel of the Slovak public service media. During her university years, she was an analyst for the only fact-checking portal in Slovakia. She was a recipient of the Novinarska Cena 2022.