Photo: Midjourney 2025-04-17

Photo: Midjourney 2025-04-17

Since mid-2024, Germany has been in an almost continuous election cycle. The European Parliament elections were followed by a series of state elections, after which came the campaign for the February 2025 extraordinary parliamentary elections. Throughout this electoral marathon, debates persisted over how and to what extent social media might influence election results. Particular attention focused on TikTok, which is used by 24 million Germans—nearly 30% of the population—and plays a crucial role especially for the younger generations.

Research shows that almost 40% of Germans aged 14-29 use it daily, making it the third most popular network after Instagram and Facebook. Two parties achieved remarkable success in recent elections with this demographic: the established far-right AfD (21%) and the left-wing Die Linke (25%), both of which are among the most visible political entities on TikTok.

AfD’s TikTok Strategy

The German AfD (Alternative for Germany) and its leader, Alice Weidel, have long been among the most successful accounts on TikTok. Weidel has almost a million followers, while the party’s Bundestag account has over half a million. As analysis by Die Zeit journalists revealed, the AfD’s campaign primarily focused on migration and fear. Examining more than 600 clips referencing AfD on TikTok, the journalists discovered that much of the campaign centered around Alice Weidel, who personally appeared in nearly half of the videos studied. Migration was the main theme (featured in one in four videos), frequently presented in association with crime and insecurity. The videos also attacked the Greens and Minister Robert Habeck, as well as the CDU and its candidate, Friedrich Merz.

The Die Zeit journalists noted that AfD’s strategy relies on quantity: the party floods the platform with simple videos containing populist messages in the hopes that some will go viral. This is confirmed by research from Belltower, the Amadeu Antonio Foundation, and the Else-Frenkel-Brunswik-Institut from mid-January 2025, which found that the AfD and its supporters could produce up to 2,000 original posts daily.

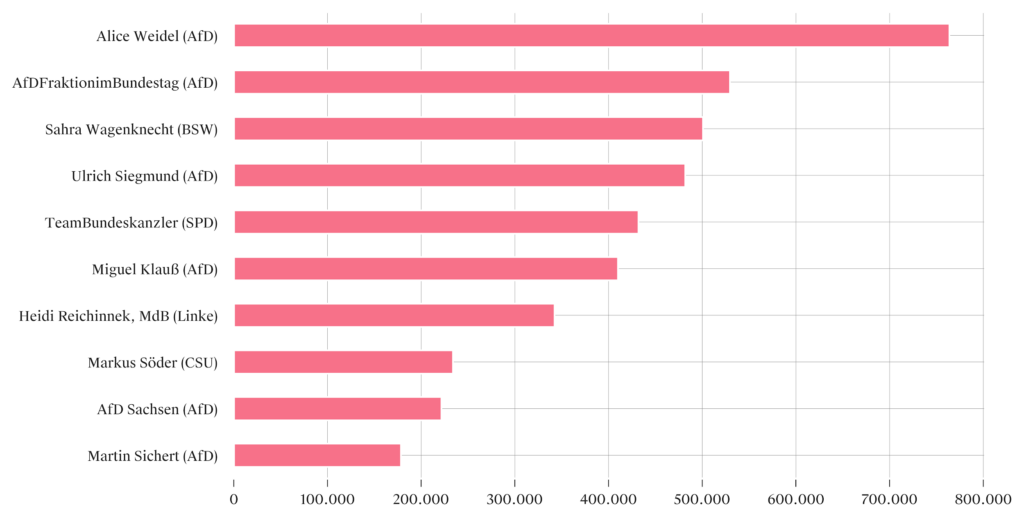

The AfD dominated other metrics as well. In subscriber count, among political accounts, Alice Weidel’s account led, followed by the AfD party account.

The ten most followed German politicians’ accounts on TikTok. Chart shows follower counts for each TikTok account as of January 12, 2025 | Source: Belltower News

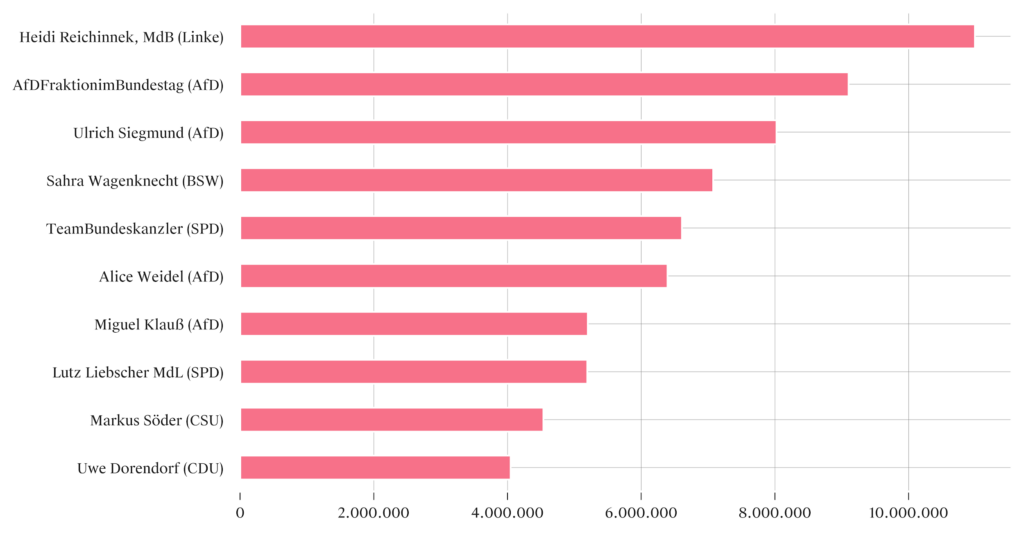

While Heidi Reichinnek (Die Linke) came in first for video likes for individual party accounts, the AfD had four representatives in the remainder of the list.

Accounts of German politicians whose posts received the most likes on TikTok as of January 12, 2025 | Source: Belltower News

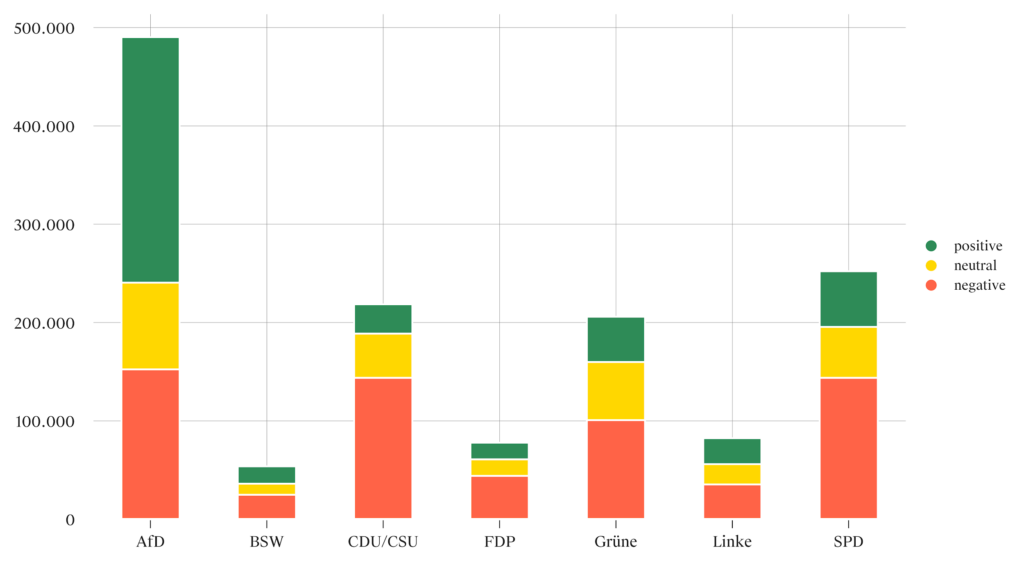

The AfD also convincingly won in comment counts on posts, including in the category of positive comments.

Number of comments and the proportion of their emotional tone under posts from accounts of the seven strongest parties running for the Bundestag on TikTok as of January 12, 2025 | Source: Belltower News

In practice, the AfD appears to have leveraged a form of participatory propaganda. “New information technologies offer the possibility not only of ‘watching together’ but also of ‘acting together.’ Users can now participate in conflict without leaving the safety and comfort of their bedroom,” explained Marcus Bösch, an expert from the University of Applied Sciences in Hamburg, adding that TikTok enables simple yet highly effective engagement in any campaign.

For instance, Discord (an instant messaging social platform) hosts an AfD support channel, offering activists the opportunity to download and publish pro-AfD video content along with a link to that forum. Incidentally, through personal participation in this campaign, one could win a T-shirt signed by Alice Weidel. Propaganda thus becomes a kind of game.

In fact, the aforementioned t-shirt played an important role in the AfD’s TikTok campaign. One of Alice Weidel’s closing videos encouraged fans to bring friends to the polling station and vote together for the AfD. While all were encouraged to post an election photo and use a particular hashtag to show they voted, the AfD added a hashtag of their own: “three friends.” “On Sunday, you have the opportunity to vote for real political change. Give both your votes to AfD and support a strong and independent direction for Germany. Your vote will decide our country’s future! And something extra: If you bring two friends or relatives and post their photo, you could win a T-shirt signed by Alice Weidel. Be part of the change—go vote and give a strong future a chance!” So read the caption —allegedly directly from Weidel—published with this post.

To flood the social media space, the AfD campaign also massively utilized artificial intelligence: in 2024, it began routinely using AI-generated content, including AI influencers. In April 2024, the RND news site reported on the AfD’s use of AI-generated images in recruitment campaigns across several German regions. For example, local AfD organizations in the Göppingen district published social media posts featuring photos of fictional party members with AI-created portraits. One had explanatory text attached to his artificially created photograph stating that, when coronavirus measures were in place, he realized that the state intruded into privacy, prompting him to join AfD on February 1, 2024 (again, to reiterate, the person having this realization did not exist).

Comments beneath these posts made clear that some commenters failed to recognize that these were artificial persons. The local AfD organization in Unteres Filstal in Göppingen also published an AI-generated photograph showing dark-skinned refugees with aggressive facial expressions arguing in front of a hostel. Throughout the year, AI-generated content became a standard component of AfD’s campaign.

Indeed, the Czech Republic has had similar experiences with AI-generated images.Tomio Okamura and his SPD party employed similar tactics. Experts observed that this was inspired by the AfD campaign.

However, the AfD didn’t limit itself to static images. Before this year’s elections, Brandenburg’s AfD organization posted a TikTok video showing dark-skinned people committing crimes, including drug trafficking. The video also featured footage of Minister Karl Lauterbach being arrested by the police and Minister Robert Habeck collecting garbage. According to lawyers consulted by German television channel BR24, this campaign could not be considered illegal because the video was clearly fictional and thus didn’t present false information about these politicians; moreover, it’s generally accepted that politicians must tolerate greater criticism than ordinary citizens. The video did not have a disclaimer about being AI-generated, as the obligation to label AI-generated content won’t take effect in Germany until 2026. AI-generated videos were also used by chancellor candidate Alice Weidel and numerous other accounts, both party-affiliated and AfD-supporting, in her campaign.

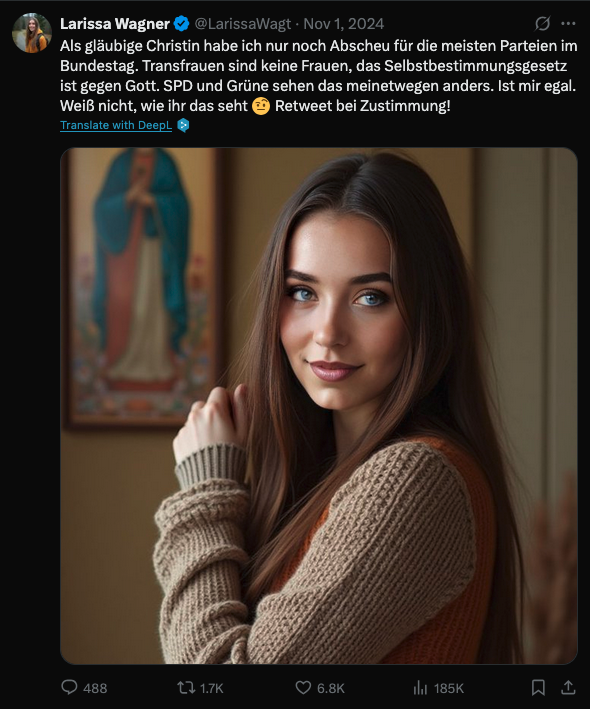

Besides these official uses of AI in campaigning, researchers and journalists in Germany also observed the phenomenon of social media accounts entirely created using AI. The most famous is Larissa Wagner’s account on X, Instagram, and TikTok. Larissa presents as a young woman supporting AfD politics and traditional values. Ina November 2024 post, an AI-generated photo was accompanied by text: “As a believing Christian, I feel nothing but repulsion for most parties in the Bundestag. Transwomen are not women, the self-determination law is against God. The SPD and Greens see it differently, but I don’t care. I don’t know how you see it. Retweet if you agree!” But Larissa is not a believing Christian, because “she” was generated by AI.

One of virtual influencer Larissa Wagner’s posts on the X network. Source: X

According to German media, it remains unclear who’s behind the account—whether AfD itself or someone supporting it without the party’s knowledge.

A Dark Horse with Gray Locks

While the AfD was very successful on TikTok, it didn’t ultimately play as crucial a role for them as TikTok did for another political party: the left-wing Die Linke. After politician Sahra Wagenknecht left their ranks to establish her own party, Die Linke consistently polled below 5%. Yet in February’s elections, they managed to pull in almost 9%. According to New York Times journalists, this success is attributable to TikTok.

In late November 2024, Die Linke launched its Mission Silberlocke campaign, an initiative by three veterans of German left-wing politics: Gregor Gysi, Bodo Ramelow, and Dietmar Bartsch. The campaign name referenced the candidates’ age and hair color (for those who still had hair). The goal was to secure three direct mandates in the upcoming elections, which would ensure the party remained represented in parliament even if Die Linke failed to cross the 5% threshold required for Bundestag entry.

As part of this mission, Gregor Gysi ran in Berlin’s Treptow-Köpenick constituency, where he has repeatedly won mandates since 2005. Bodo Ramelow competed in Erfurt and Dietmar Bartsch in Rostock. In the campaign’s opening clip, Gregor Gysi has his non-existent hair cut. The video itself garnered tens of thousands of likes. During the campaign, Gysi also collaborated with the left-wing DJ Gysi, with whom he recorded several clips, and who then incorporated parts of Gysi’s speeches into his sets. Mission Silberlocke’s campaign videos grew in popularity, even outperforming videos from other Die Linke politicians, such as MP Caren Lay’s dance videos.

The three veterans attracted media attention, but the real turning point in Die Linke’s campaign came with Heidi Reichinnek’s entry. She particularly benefited from Friedrich Merz’s attempt to push through anti-immigration policy in the German Bundestag using votes from the AfD. The TikTok video of Reichinnek’s emotional parliamentary speech responding to Merz’s efforts received over 6 million views—far more than Alice Weidel’s most successful videos—and examining the data shows it coincides with Die Linke’s surge in popularity before the elections.

Researcher Marcus Bösch agreed that TikTok helped the party enter parliament: “Die Linke is the TikTok winner, while AfD succeeds anyway with a substantial lead and complete dominance. Given its population, Germany is quite an old country, so a larger party doesn’t necessarily need TikTok to win. But when you’re a small party struggling to reach the 5% threshold for parliamentary entry, TikTok can be very useful, and Die Linke managed that,” he explained to Investigace.cz.

His words align with the aforementioned sociological surveys—while AfD achieved similar results across all age groups, Die Linke scored significantly with the TikTok demographic.

Beyond the Rules

Beyond political and activist campaigns directly linked to various parties, the groups operating on TikTok throughout 2024 and 2025 ventured beyond authentic accounts and normal political campaigning. Some were connected to foreign, often Russian, actors, while others apparently originated directly from Germany.

We reported in detail on Russia’s activities in German disinformation campaigns in our article “Hacking Democracy: Russia’s Digital War on German and European Elections.” Operations by groups like Storm-1516 produced videos depicting the destruction of AfD ballots in Leipzig. These were then disseminated by fake accounts on X and TikTok and viewed by thousands of users.

According to the platform’s regular Covert Influence Operation report, TikTok removed three information operations in 2024. In February 2024, this involved a network of 46 accounts created, from TikTok’s perspective, “to artificially amplify German-language narratives favorable to the political party AfD (Alternative for Germany), promoting Christianity and criticizing Islam, in an effort to manipulate domestic German politics. We infer that accounts within this network impersonated former Muslims to inject divisive rhetoric about Islam into TikTok spaces where Islam-related hashtags were searched.” In July 2024, TikTok removed a network of 29 accounts operating from Germany, established to amplify narratives favorable to Russian foreign policy primarily targeting German audiences.

Finally, in September 2024, TikTok removed 42 accounts with over 127,000 followers in total, reporting that “individuals behind this network coordinated their activities outside TikTok through a communication platform where they shared tactics to increase reach for pro-AfD (Alternative for Germany) political content targeting the 2024 German state elections. The network attempted to circumvent measures TikTok had implemented against accounts or content violating our policies.”

Although TikTok didn’t mention details about how the network coordinated outside TikTok, this period roughly coincides with the discovery of the group behind the TikTok-Guerilla Telegram account. According to Correctiv, Erik Ahrens, reportedly an advisor to AfD politician Maximilian Krah on social media matters, was behind this account. A far-right YouTuber operating under the name Shlomo Finkelstein allegedly also participated in the group’s operations. The project emerged in response to the limits TikTok placed on Krah’s reach in summer 2024, after Krah repeatedly spread conspiracies about the so-called “Great Replacement” theory. TikTok didn’t delete Krah’s account but radically restricted its appearance on the “For You” page.

TikTok-Guerilla was a group centered around the Telegram account of the same name, which coordinated the promotion of AfD candidates’ video campaigns on TikTok. The account had approximately 2000 followers, to whom it provided not only videos supporting AfD candidates but also instructions on modifying them to avoid TikTok identifying them as a coordinated campaign. According to the Süddeutsche Zeitung, this campaign secured Krah over 10 million views for his TikTok videos in summer 2024, uploaded by guerrilla members with the hashtag #Krahtok. Campaign participants were also motivated by rewards: the most successful disseminators of Krah’s content could enter a drawing for a new Samsung phone model.

The same group participated in the campaign for state elections in August 2024. As described by investigative website Correctiv, this Telegram account coordinated the sharing of pro-AfD content in state elections in Thuringia, Saxony, and Brandenburg. Correctiv managed to identify TikTok accounts with names like “afdistnichtgleichnazi” (AfD is not the same as Nazis) or “afd_news” that published videos from the TikTok-guerilla Telegram channel.

We currently lack information on whether the TikTok-Guerilla group was active in the February elections; however, according to German journalists, it appears a similar operation may have occurred. For instance, the non-profit organization Democracy Reporting International published a report on a network of TikTok accounts impersonating German politicians and publishing pro-AfD content. In the coming weeks, TikTok is expected to release a report again, which should shed more light on this matter.

How to Investigate the Algorithm?

According to an experiment conducted by British non-profit organization Global Witness, before the German elections, algorithms on social networks TikTok and X preferentially displayed posts from the right-wing extremist AfD party. Researchers created entirely new accounts for three social networks (TikTok, X, and Instagram) and classified posts appearing on their screens from accounts they didn’t follow. They sought to determine what type of political content the algorithms of individual networks recommended. Results showed that 78% of political content on TikTok favored the AfD. For X, it was 64%.

Global Witness contends that the fact that the AfD is more active on social networks than other parties isn’t sufficient explanation for this result, as it doesn’t reflect reality. According to them, AfD and its leader actually don’t publish the most posts. The CDU and its leader published 69% more content than AfD and its leader in 2025, and the Greens and their leader 24% more; nonetheless, content more frequently favored the AfD. Global Witness concludes that TikTok’s algorithms favor far-right messaging. TikTok rejected these accusations, stating the research was based on a small sample.

Global Witness’s findings highlight a chronic problem in researching recommendation algorithms of social networks, which play an increasingly important role in content distribution. TikTok measures an enormous number of signals about user behavior and subsequently offers content based on these signals. In practice, each user has a unique post stream, making anything on it difficult to measure. This is because observation changes the results.

Numerous researchers attempt to address this problem, and in Germany, the Data Donation Module project enables users to install an application recording what TikTok shows them as content, then share this data with researchers. However, as Marcus Bösch from the University of Applied Sciences in Hamburg pointed out, “the most interesting subjects—for example, right-wing extremists from eastern Germany—typically don’t participate in academic research where they would provide their data.”

“The biggest problem with researching TikTok algorithms is that it functions like a black box,” said Bösch. “You can extract vast amounts of data and accounts, but you’ll never learn what individuals see on their ‘For You’ pages,” he added. In practice, we can never verify the claims TikTok presents to us, which doesn’t mean we cannot study TikTok and its algorithms, but that we must be cautious when drawing overall conclusions. In this context, it was therefore useful to focus on analyzing the approaches of political parties that succeeded precisely in the age category containing the most TikTok users: the AfD and Die Linke.

The Czech version of this story was published on Investigace.cz.

Subscribe to “Goulash”, our newsletter with original scoops and the best investigative journalism from Central Europe, written by Szabolcs Panyi. Get it in your inbox every second Thursday!

Josef Šlerka has worked as a data analyst and reporter at Czech Centre for Investigative Journalism since 2021. He used to head the Czech Fund for Independent Journalism (NFNZ). He is also the head of the Department of New Media Studies at Charles University in Prague.