For over twenty years, the European Anti-Fraud Office (commonly known as OLAF, from the French: Office européen de lutte antifraude) has been protecting the EU’s financial interests, investigating fraud, corruption, and serious misconduct within the Union’s budget and institutions. The office has also developed an anti-fraud policy for the European Commission.

But while OLAF looks into a wide range of wrongdoings, from misconduct in public procurement procedures, to customs fraud and document forgery, very little is publicly known about the impact of its investigations in the Visegrad region, where the fact of EU fund embezzlement has been common knowledge since the countries joined the bloc in 2004. OLAF has no judicial powers to oblige national law enforcement authorities to act upon its follow-up recommendations, and as the region’s governments have shown, its advice is not always taken seriously enough.

Between 2014-2018, OLAF concluded almost 1200 investigations across the EU and recommended that the European Commission recover over €6.9 billion to the EU budget. It issued almost 1700 recommendations for judicial, financial, disciplinary and administrative actions to be taken by relevant authorities in respective member states and the EU. When OLAF was asked, however, about the extent and nature of these fraudulent activities in the Visegrad region, it was reluctant to provide any specific information to the public.

Some data on the countries can be found in the OLAF yearly reports: One from 2018 states that altogether 95 of the concluded investigations in the areas of European Structural and Investment Funds and Agriculture carried out between 2014 – 2018 concerned the Visegrad region countries — that is, Poland, Hungary, Czech Republic and Slovakia.

The total financial recommendations to recover EU funds made by OLAF in those four years was 0.45 percent of payments. For some of the Visegrad region countries, those numbers are lower.

Hungary tops the list of countries in which the agency recommended the recovery of EU structural and investment funds and agriculture subsidies. Here, OLAF concluded 52 probes into misuse of funds and recommended the recovery of 3.84 percent of EU payments.

Slovakia comes in second with a recommendation to recover 2.29 percent of funds following 14 investigations that uncovered some sort of irregularity.

In Poland, 22 investigations resulted in a recommendation to recover 0.12 percent of the payments, and in the Czech Republic, seven investigations resulted in a recommendation to recover 0.06 percent.

VSquare reporters tried to learn more about the specific cases that were investigated in each of these countries from both OLAF and from national agencies.

The OLAF investigations we were able to learn more about often concerned misuses of funds earmarked for agriculture. For example, following an investigation by OLAF, the prosecutor’s office in Siedlce, Poland began investigating irregularities in funding obtained by a conglomerate in northern Poland that grows and processes vegetables — irregularities that included inflating costs and using fraudulent VAT invoices.

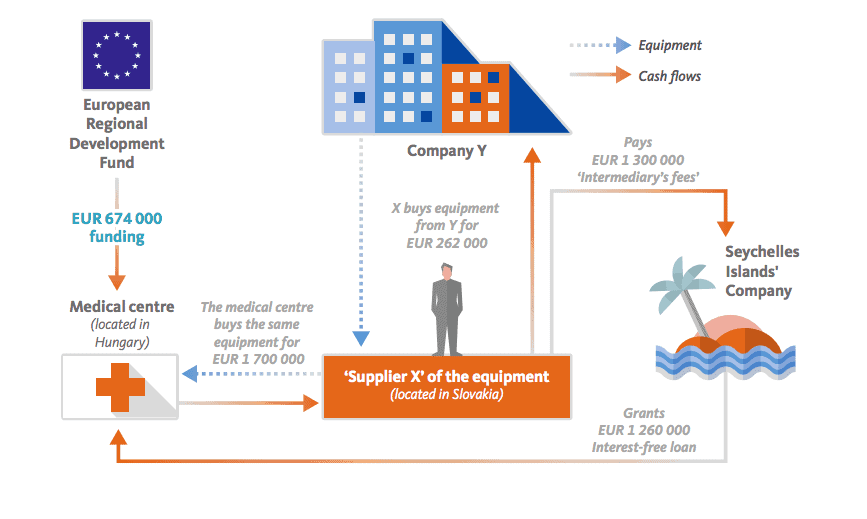

We found that the nature of the irregularities were similar across the Visegrad countries: using fake documents or fake expense certifications when applying for the funds, overinflating the cost of services and equipment in public tenders, applying for tenders with no intention of actually realising the projects. In one case in Hungary, a medical center claimed it purchased equipment worth EUR 1,7 million. As it turned out, the supplier for the center had purchased the medical devices for only EUR 262,000 from a company in Slovakia. The supplier then paid EUR 1.3 million of the sale price in ‘intermediary fees’ to a company registered in the Seychelles. In return, the latter provided an interest free loan of EUR 1.26 million to the medical centre. The whole operation was aimed at quadrupling the declared prices of the medical devices and circumventing the EU obligation on the medical center to provide a financial contribution of their own to the project. The Hungarian authorities that subsequently investigated the case also found that the medical center employed naturopathic doctors instead of licensed clinical doctors.

The Hungarian fraud scheme as described by OLAF

Some of the cases turned up were already high-profile, such as the case of Stork’s Nest Farm in the Czech Republic, which is connected to Prime Minister Andrej Babiš’ Agrofert company. Although OLAF concluded that there was “false and concealed information” in the farm’s grant application and suspected the company of subsidy fraud and of harming the financial interests of the European Union — findings that were replicated by the Czech police — Czech prosecutor Jaroslav Šaroch put a halt to all proceedings against the accused in fall 2019, saying that while there were “highly above-standard relationships” between the Stork’s Nest Farm and the Agrofert companies, that the Stork’s Nest Farm could still be viewed as a small to medium-sized business. Šaroch added that there was no proof of intent to deceive on the subsidy application.

OLAF data shows that in Hungary, action was taken by relevant national authorities following OLAF’s recommendation 45 percent of the time between 2012 and 2018. In Poland this number figured to 78 percent, while it was only 25 percent in Slovakia, and 14 percent in the Czech Republic. The EU average was 36 percent during these six years.

Read more about Hungary: Hungary rules Botched Subsidies

Read more about Poland in: EU funding fraud in Poland we know little about

Read more about Slovakia in: Slovakia: The Countess and The Farmer

This text was financially supported by GACC (The Global Anti-Corruption Consortium) aimed at the Visegrad countries. Member centers Átlátszo and Direkt36 from Hungary, Fundacja Reporterów from Poland, Ján Kuciak Investigative Center from Slovakia and investigace.cz from the Czech Republic are working on the project.