Sofiya Maksymiv, Darya Kuzmina, Trap Agressor (Ukraine)

Collaboration: Daniel Flis (FRONTSTORY), Oleksandr Generalov (Trap Aggressor)

Illustration: Trap Aggressor 2025-08-04

Sofiya Maksymiv, Darya Kuzmina, Trap Agressor (Ukraine)

Collaboration: Daniel Flis (FRONTSTORY), Oleksandr Generalov (Trap Aggressor)

Illustration: Trap Aggressor 2025-08-04

- Right under the noses of Polish officials, a network of companies is importing sanctioned goods into Russia. At its center is a firm based in Gdynia, a city on Poland’s Baltic coast.

- The key figure in the scheme is a politician from Putin’s United Russia party, who is also involved in training future conscripts for the Russian army in Kaliningrad.

- His company works with the state-owned Russian nuclear giant Rosatom, while his Polish partners openly boast about ties to a strategic Polish fuel company.

- Polish authorities appear unable—or unwilling—to address even this blatant case of sanctions violations.

Every day, Russia rains hundreds of deadly drones on Ukraine. Civilians, including children, are killed in the attacks. In response, the European Union imposes further sanctions on the Kremlin. In theory, those who continue to trade with Russia despite the bloody war should lose out and close their businesses. In practice, however, the most brazen are thriving in the new reality, officially serving customers in the EU while quietly fueling the Russian economy.

Together with experts from Trap Aggressor, a project run by the Ukrainian analytical center StateWatch, we have tracked down one such company. Despite the sanctions and bans, it finds loopholes to supply key products—from microelectronics to specialized industrial components—to Russia. This is possible thanks to a network of intermediaries from Turkey, Kazakhstan, and Poland. To hide what it really does, the company has created a network of companies and websites that allow it to circumvent restrictions.

We have examined this arrangement. There are many indications that neither the Polish services nor the Polish administration have done a similar investigation.

Putinist in Stawiguda

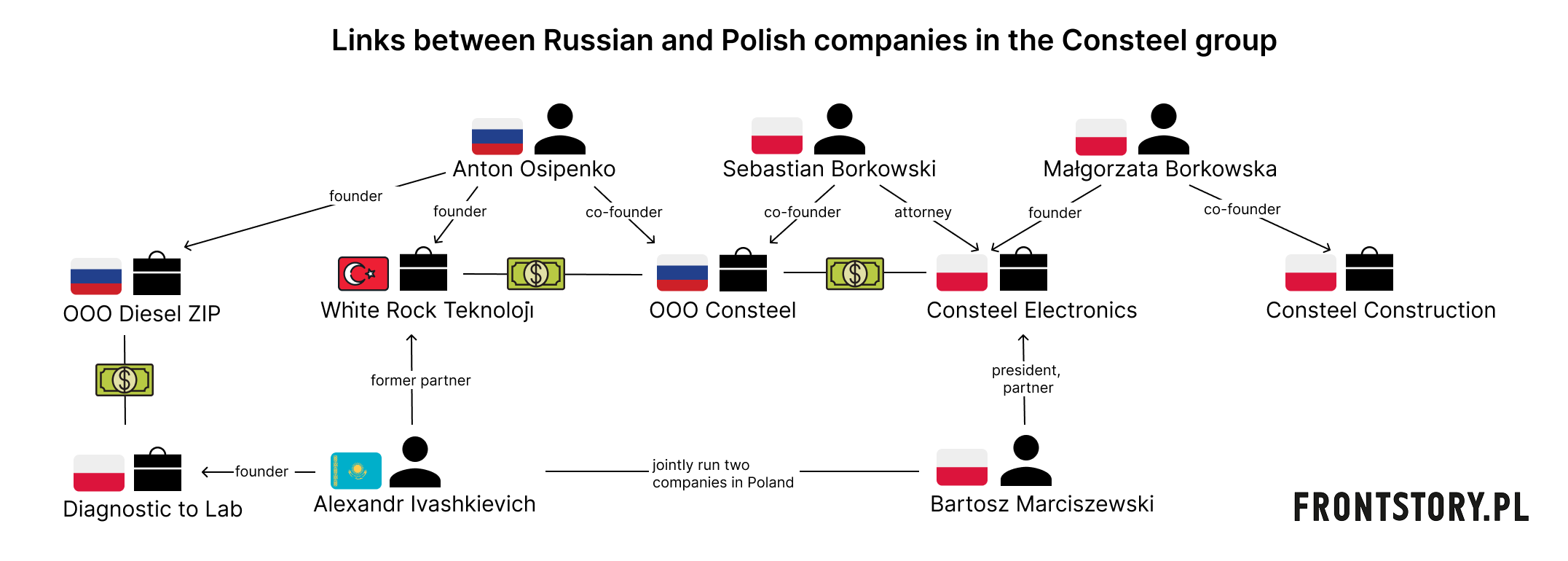

This story begins fifteen years ago in Kaliningrad. In 2010, Russian businessman Anton Osipenko founded OOO Consteel (“OOO” being “Ltd” in Russian). The company was involved in a wide range of industries, from trade and construction to logistics. He did not set it up alone: his partner was a Pole, Sebastian Borkowski. In that same year, a new Polish-Russian border crossing was opened in Grzechotki. Over the next 15 years, the Russian and Polish business grew into an international group of companies linked to the same people.

Who is Anton Osipenko? He is a well-known figure in Kaliningrad Oblast. In 2004, he was convicted of preparing and attempting to commit crime and theft, and was a former councilor in Mamonovo, a small town five kilometers from the Polish border. Later, beginning in 2016, he represented Putin’s United Russia party for several years in the local government.

In 2017, Councilor Osipenko arrived in Poland as an official representative of the Russian authorities. In Stawiguda, in the province of Warmian-Masurian, he signed a letter of intent on cooperation (Poles and Russians wanted to obtain €2 million from EU funds, among other things, for the renovation of cultural centers on both sides of the border). Documents bearing the Mamonovo coat of arms—crossed axes against a rising sun—landed on the desks of Polish officials.

In a 2017 interview with local television, Anton Osipenko, a burly man with a crew cut and a Russian flag on his lapel, speaks fluent Polish. With a stony face, he makes plans for a cultural festival.

According to him, it would start in Stawiguda and end in Mamonovo. The program would include the artistic and culinary achievements of both towns and would feature local artists, music bands, and Polish and Russian traditions.

We have repeatedly tried to talk to the mayor of Stawiguda about these plans, but he has not responded to our requests for comment.

Local government activism is only one of Osipenko’s faces. At the same time, he is building a business network in Poland—one that is much more lasting than ideas for exchanging local artists and pierogi-making techniques.

Together in Business and in St. Petersburg

Who is Sebastian Borkowski, Osipenko’s Polish partner? Little is known about him other than that he is a graduate of the University of Warmia and Mazury in Olsztyn. And that he has been doing business with the Russian politician since 2010.

In 2015, Małgorzata Borkowska, most likely a relative of Sebastian, registered a company in Gdynia with a name similar to that of Osipenko’s Russian company: Consteel Construction. The company is involved in construction and electrical installations for industry. On its website, it boasts of projects completed in Ukraine, Poland, and Germany, among others, and lists LOTOS Group, for which it performed locksmith work, among its clients. It is a medium-sized or small business. Until 2022, its revenues did not exceed a few thousand. It was only after the invasion that they increased fivefold to PLN 150,000. In the following years they exceeded PLN 1.5 million.

The “shop” tab on the Consteel Construction website redirects customers to the Consteel Electronics website, another business of the Borkowski family. Małgorzata Borkowska founded this company in 2017. It is a distribution and logistics company dealing with automation and industrial electronics. Interestingly, Małgorzata’s company’s business profile is almost identical to that of the Russian company Osipenki, which has a financial situation similar to that of its sister company Consteel Construction. Before the invasion, its revenues did not exceed PLN 10,000; in 2023, they already amounted to PLN 6 million.

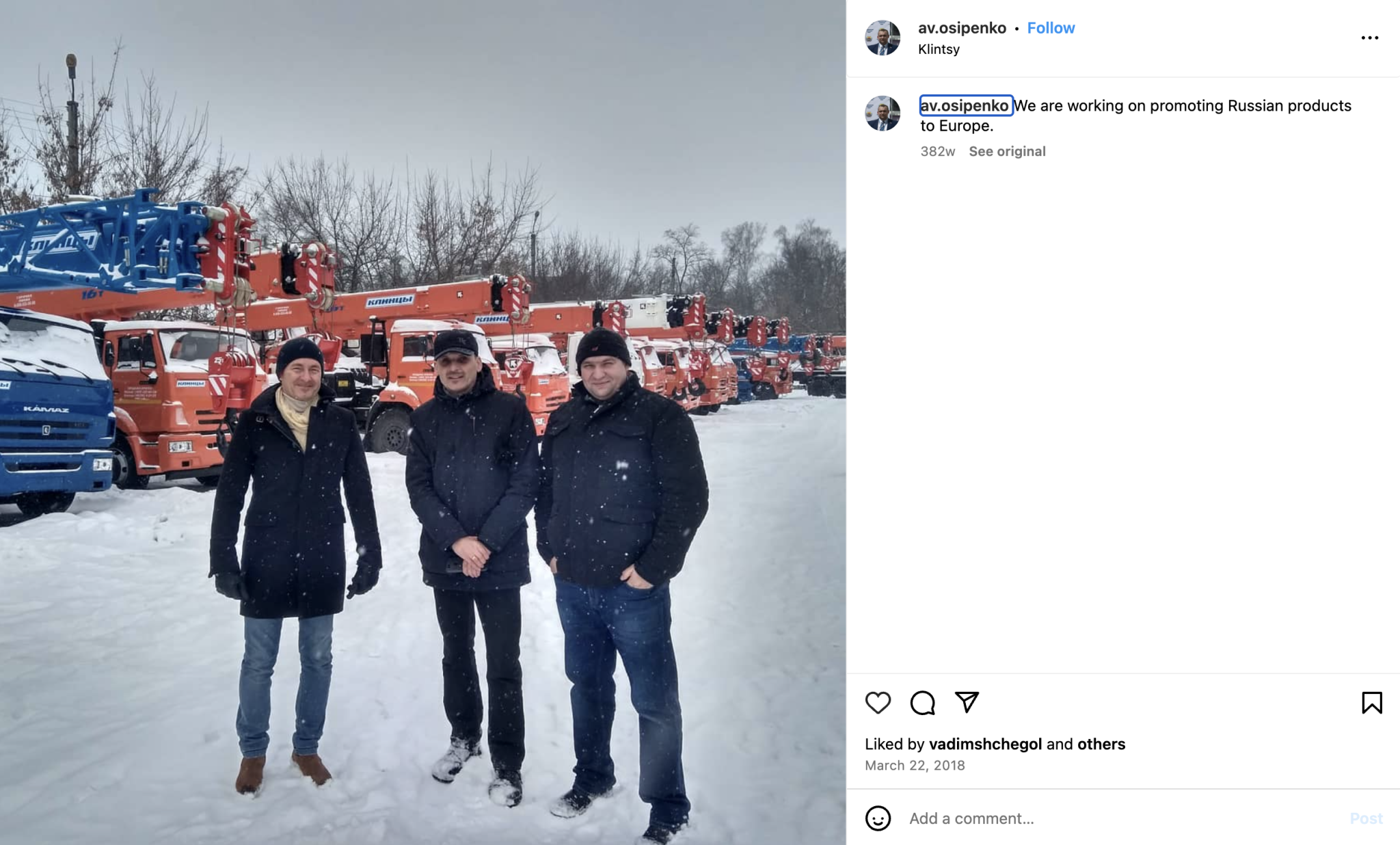

Since early 2018, Osipenko himself has been posting photos from his trips to Poland on social media. He invites Polish partners to Russia and posts reports of their visits on Instagram. One of the photos shows Russian mobile cranes. The caption reads: “We are working on introducing Russian products to the European market.”

Screenshot from Anton Osipenko’s Instagram profile

In another photo from 2020, Osipenko poses in St. Petersburg with Sebastian Borkowski.

Screenshot from Anton Osipenko’s Instagram profile

We Will Help You Pretend to be Polish

Shortly before Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Osipenko’s Instagram posts stopped. He also stopped publicly mentioning his cooperation with Poles.

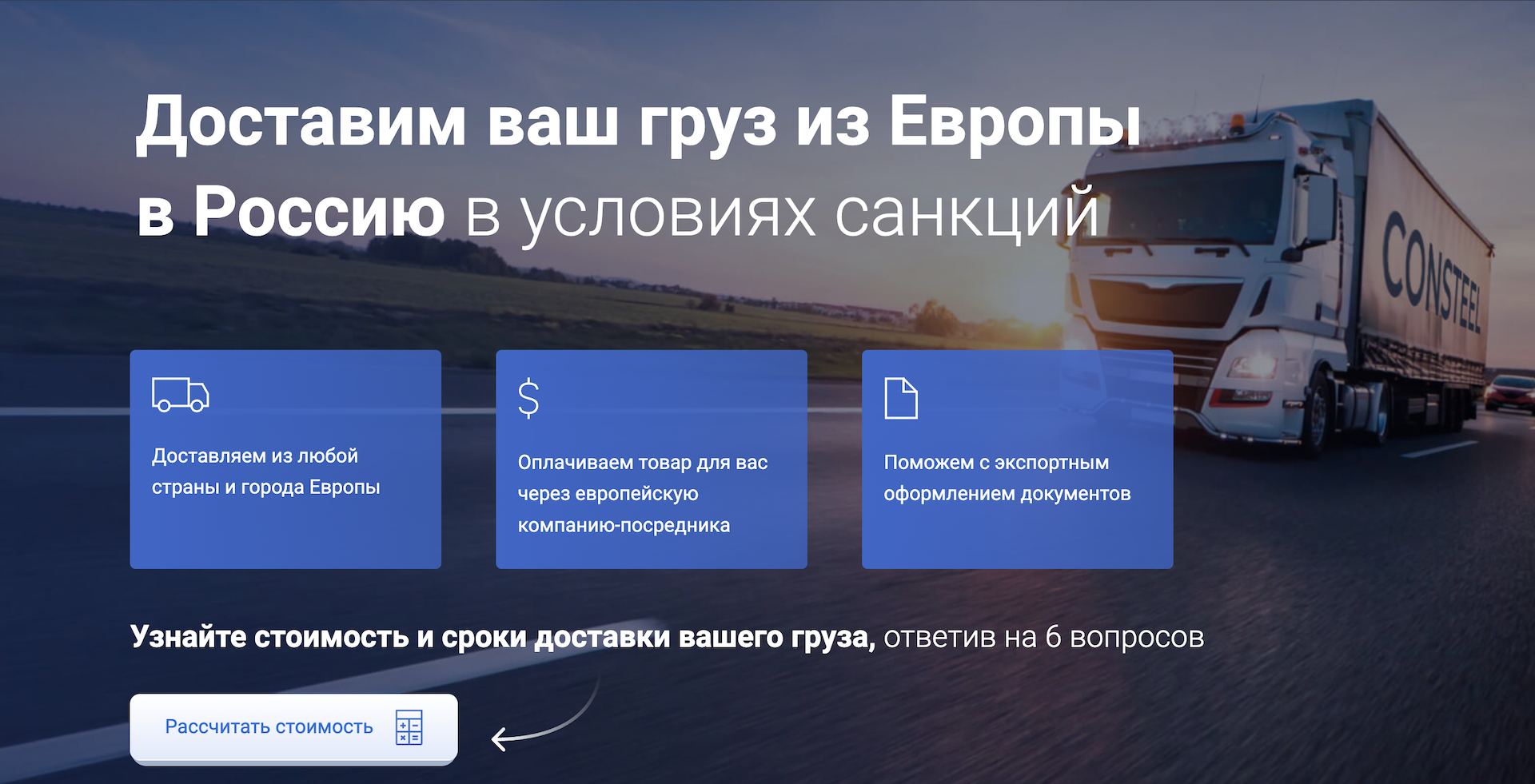

When, in the fall of 2022, the European Parliament approved the eighth package of sanctions—another attempt to restrict the access of Vladimir Putin’s regime to technology, goods, and money—a new website appeared online: Consteel Cargo Russia. What does it do? Its website leaves no doubt. In large Russian letters, the slogan reads: “We will deliver your cargo from Europe to Russia under sanctions.”

Screenshot from consteel-russia[.]ru, accessed on October 12, 2022.

Consteel Cargo Russia also boasts that it has a warehouse in Gdynia. This, its website claims, allows it to carry out “smooth purchases and deliveries of European equipment even in the current situation.”

We have established that the platform is backed by the Russian company Osipenki and Borkowski. We have many questions for the latter: why is a Polish-owned Russian business so openly offering Russians a way to circumvent sanctions? How much does he earn from this? Does the dirty money go to Poland or elsewhere? What connects the network of Polish and Russian companies apart from the common element “Consteel”? Where exactly is the warehouse in Gdynia and what goods does it store?

Consteel Electronics does not operate at its official address in Gdynia. When we visit in person, the receptionist of a small office building explains that the company moved to Sopot a few months ago.

The building where Consteel Electronics rents an office, Sopot. Author: Daniel Flis, FRONTSTORY.PL

In Sopot, Consteel occupies several rooms in a four-story office building. Sebastian Borkowski is not there, but we find the company’s president and co-owner, Bartosz Marciszewski. We ask him about Osipenko. “Anton? He’s our client,” he admits.

“Why does your Russian client’s company have the same name as yours?,” we ask.

“We allow our clients to use our name,” Marciszewski blurts out.

“And why is Mr. Borkowski, the proxy of the Polish Consteel, a co-founder of the Russian Consteel? What is going on here?”

“Ask Sebastian,” the CEO says, cutting us off (Sebastian Borkowski does not respond to our request for a meeting, nor does he answer the questions we send him).

When we show Bartosz Marciszewski, president of the Polish Consteel Electronics, the Consteel Cargo Russia website (the one with the offer to circumvent sanctions), he is surprised. He claims he has not heard of it before. He asks us to send him screenshots and announces: “The first thing I’ll do is call Anton and ask him what’s going on. Did he really plan something like this? I had no idea about it.”

A few hours after our conversation, the Consteel Cargo Russia platform disappears from the internet. In its place appears a message in Russian: “We’ll be back soon.”

Atomic Rosatom Thanks Consteel

According to Trap Aggressor data, the first shipment from Consteel in Poland arrived in Russia in 2018. By the start of the full-scale invasion, there had been 316 such shipments worth $203,000.

Bartosz Marciszewski, president and co-owner of Consteel Electronics, recalls in an interview that before the sanctions were imposed, Russian customers accounted for only about 5 percent of the company’s turnover.

Photo: Consteel Electronics Facebook page. First from the left – Anton Osipenko, fourth from the left – Sebastian Borkowski at the Consteel office, 2019.

He assures us that since the sanctions were introduced, exports to Russia have been impossible.

Perhaps this is why, in July 2023, Anton Osipenko established Consteel Teknoloji̇ (later renamed Whi̇te Rock Teknoloji̇) in Antalya, Turkey.

We have established that since the outbreak of the war, the Turkish and Polish Consteel companies have delivered goods worth at least $1.3 million to Russia. These include goods covered by sanctions. More than half of the deliveries are dual-use goods: data transmission devices. According to Marciszewski, they are used in building management systems. However, the European Union has imposed sanctions on them because, apart from civilian use, they can be used by the Russians for secure communication on the battlefield.

On the Russian Consteel website, we find letters of thanks for the timely delivery of equipment from Italy, Spain, and Germany. Among the customers are Russian and Belarusian companies, both private and state-owned. In August 2022, Russian Atomstroyexport, the contractor for the construction of a nuclear power plant in Belarus and part of the Russian state-owned Rosatom concern, expressed its gratitude for the delivery of Italian equipment for production automation.

Osipenki’s other businesses operate according to a similar pattern. In Russia, he owns Diesel ZIP, a company that imports spare parts from companies that have left the Russian market or are subject to export bans (including Volvo, Ford, and Mitsubishi).

Who does Osipenki’s automotive company work with in Poland? According to Trap Aggressor, its supplier is Diagnostic To Lab, a company founded by Aleksandr Iwaszkiewicz, a citizen of Kazakhstan. Outside the EU, the company supplies products exclusively to Russia. Since the outbreak of the war, it has sold goods worth $2.5 million. To whom? To Osipenki’s company, Diesel ZIP.

In Russia, Aleksandr Iwaszkiewicz runs the company OOO ITS along with Osipenka. The president of the Polish Consteel, Marciszewski, knows Iwaszkiewicz: they run two companies together. Marciszewski does not mention this during our meeting. He only says that Aleksandr, with his Turkish company, is one of his customers.

Experts from the British think tank RUSI (Royal United Services Institute) explain that before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, there were no provisions in Polish law providing for penalties for violating sanctions. The relevant law was passed in 2022 and has not been amended since. It was not until February 2025 that provisions were introduced providing for criminal liability for violations of sanctions in force at that time. This means that even if Consteel Electronics violated the law in 2024, there is a risk that it cannot be punished for this due to a lack of relevant criminal provisions related to the application of EU sanctions.

We asked the Polish Ministry of the Interior and Administration whether it had conducted or was conducting an investigation into Consteel Electronics for circumventing sanctions.

The ministry has traditionally refused to provide us with any information. Since 2022, we have published 12 articles about companies violating sanctions. Only one of them, owned by Oleg Deripaska, has been included on the sanctions list.

Although the Consteel case is clear (the company openly offers to circumvent sanctions), neither EU institutions nor Polish authorities are able to respond effectively to such cases.

Hobby: Putinist Patriotism

Should the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Administration take a closer look at the network of companies under the Consteel banner? Without a doubt. Their Russian partner, Osipenko, is not limited to business: in his spare time, he is involved in the patriotic military education of Russian youth. In Russia, this means activities in line with the Kremlin’s official propaganda. In 2012, Osipenko and two other Russians founded the Kaliningrad Regional Youth Organization “Association of Russian Martial Arts,” a project that the Russian regime supports financially.

We have established that in 2021 and 2023, Osipenko’s organization received 1.2 million rubles (approximately 12,000 euros) from the state to organize training, competitions, and preparation for future conscripts—people who will murder Ukrainians as part of Vladimir Putin’s full-scale invasion.

Although Osipenko has limited his presence on social media since the outbreak of the war, he previously appeared at events attended by Russia’s top officials. In one photo, we found him next to Dmitry Peskov, the Kremlin spokesman.

Photo from Dmitry Chumakov’s VKontakte page. Event organized by the Russian Martial Arts Association, 2021. Anton Osipenko on the right.

While the European Union is struggling with and delaying the adoption of its 18th package of sanctions, Russia is preparing for a longer march forward where sanctions are concerned. As noted by T-Invariant (a Russian science website), in the coming academic year, the Higher School of Economics in Moscow will launch the country’s first master’s degree program dedicated to circumventing international sanctions.

The university is advertising the program as a pioneering course where students will learn to “identify and assess sanctions risks and other negative actions by supervisory authorities against companies.”

Similar courses have also been launched by Moscow State University (MGU), where, in accordance with Putin’s decree, a scientific and educational center for sanctions compliance is being established.

The original version of this investigation was published in Polish on FRONTSTORY.PL.

Subscribe to Goulash, our original VSquare newsletter that delivers the best investigative journalism from Central Europe straight to your inbox!

A Warsaw-based investigative and data journalist at VSquare and Frontstory.pl, Anastasiia Morozova previously collaborated with leading media outlets in Ukraine (Radio Free Europe, Slidstvo.info). She was shortlisted for the Grand Press Award (2022) and was a recipient of the Novinarska Cena 2022.

An investigative journalist at FRONTSTORY.PL, Daniel Flis previously was on the investigative team of OKO.press and Gazeta Wyborcza. OCCRP Research Fellowship Program recipient. Participant in international investigative projects of the Reporters Foundation.