Illustration: James O'Brien/OCCRP 2025-05-29

Illustration: James O'Brien/OCCRP 2025-05-29

- Documents from the Pravfond fund reveal how Russia finances its support in Poland

- Who takes money from a special fund from Moscow? And for what activities?

Legal aid for those accused and convicted of espionage. An organization of conferences and rallies of support. Renovations for Red Army monuments.

All this appeared in documents we obtained from a Russian fund used by the Kremlin to finance its activities in Poland.

Who is accepting money from Putin? A colorful crowd: lovers of World War II monuments, journalists, and businessmen with gaps in their CVs. Add to that law firms, historical associations, and marginal political parties. The Kremlin’s Fund for the Support and Protection of the Rights of Compatriots Living Abroad, known as Pravfond, is their money tree.

We have obtained documents that show who is receiving money for supporting Russia in Poland and how much they are getting. We have evidence that four pro-Russian activists and spies (as well as their lawyers) received €33,000.

The documents also show that, despite sanctions imposed by the European Union, in 2023, Pravfond continues to send money to recipients in European countries, which may constitute a violation of the sanctions.

Several European intelligence agencies consider Pravfond to be a tool of Russian intelligence.

Rubles to support compatriots

Everyone knows that the Kremlin is active in Europe through its own institutions. We have now found evidence of cooperation between pro-Russian Poles and a Moscow-based government fund for the support and protection of compatriots living abroad. This is the so-called Pravfond, which, since its inception 14 years ago, has awarded at least $6.3 million to beneficiaries in Europe, the United States, and Australia, among other places. Officially, the fund’s goal is to support the Russian diaspora. In practice, Pravfond works as an extension of the Russian intelligence services. The amount of support is not staggering, but it is not about the amount of individual payments, but silent influence and support for activities that are convenient for Moscow.

How do we know this? In the Pravfond data collection, which was obtained by reporters from DR (Danish public broadcaster), we found over 49,000 emails and 22,000 documents from the fund. Among them were over 360 grant agreements. Using the fund’s numbering system, we were able to conclude that the fund also awarded 713 additional grants (which are not included in the leaked archive). The leaked emails were sent or received by a total of at least 21,000 people.

Twenty-eight newsrooms, including FRONTSTORY.PL and VSquare, took part in the investigation coordinated by the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP).

We have established that Pravfond’s support was used by Leonid Sviridov (an alleged journalist, expelled from Poland in 2015, who died recently); Mateusz Piskorski, accused of spying for Russia and China; and Stanisław Szypowski, a businessman convicted of espionage. Smaller but significant roles were played by Russian women — Yekaterina Tsivilskaya and Anna Anastasia Zakharian (also eventually expelled from Poland), as well as journalists and politicians.

Our protagonists are linked not only by common interests and views, but also by funding from the Kremlin. The Polish security services — the Internal Security Agency (ABW), the Border Guard, and the courts — are aware of the actors in this story and their connections.

In this story about Russian actions in Europe, there are no explosions or saboteurs. There are gigabytes of data, hundreds of emails, strange transfers, and unexplained coincidences.

And we have compatriots everywhere

Pravfond for beginners: an office like any other, with about 18 employees in several rooms in the center of Moscow, right next to Arbat Street, a famous pedestrian thoroughfare.

Pravfond in the eyes of Western services: a Kremlin tool for propaganda, disinformation, and influence operations. The actions it sponsors are intended to destabilize Europe. “The fund was created to finance influence operations under the guise of fighting discrimination against Russians,” explains Marta Tuul, spokeswoman for KAPO, the Estonian security service. “It is an extension of the Russian intelligence services, enabling control over the Russian-speaking diaspora.”

Not all of Pravfond’s activities are political in nature. In line with its (public) mission, the organization also provides assistance to ordinary Russians abroad. It helps in child custody disputes and facilitates access to doctors.

But it was Pravfond that financed, among other things, legal assistance for Viktor Bout, an arrested arms dealer, and for Vadim Krasikov, an FSB agent who murdered a Chechen fighter in Berlin. Both were convicted and handed over to Russia as part of a high-profile prisoner exchange. Several key figures in the Fund’s structure, including its deputy head, Vladimir Pozdorovkin, are former Russian intelligence officers.

In recent years, Pravfond has provided assistance to, among others, a man accused of attempting to blow up a Latvian drone base; a man convicted in the Czech Republic for leading an armed gang during the annexation of Crimea; and an Australian activist who sought refuge in the Russian consulate in Sydney after assaulting a supporter of Ukraine. Pravfond also provides direct funding for propaganda and influence operations — for example, it financed the publication of a history textbook on Lithuania that justifies the Soviet occupation of the country, and it also financed pro-Russian channels on Telegram.

Leaked emails show that, despite sanctions imposed by the EU in 2023, Pravfond continues to send money to recipients in Europe, and primarily in the Baltic states and Ukraine. These are “priority regions”, as Pozdorovkin describes them in one of the emails. It is there that “our compatriots found themselves against their will.” The view that millions of former Soviet citizens in neighboring countries are part of the Russian world is widespread in Russia and is enshrined in Russian federal law.

The director of Pravfond is Alexander Udaltsov, who replaced the late Igor Panevkin (the latter was asked for financial support by Leonid Sviridov and Jerzy and Anastazja Tyc).

Who is the gap in the CV for?

In Pravfond’s correspondence, we found agreements with Russians accused and convicted in Europe for espionage. One of them is Stanisław Szypowski, a 39-year-old lawyer whose story was covered by FRONTSTORY.PL in January.

Five months after Szypowski was detained by Polish authorities in 2014, Pravfond granted him reimbursement for legal fees. The spy company received $1,420 for this purpose. The agreement bears his signature and stamp. In an interview with FRONTSTORY.PL, Szypowski declined to comment on the transfer.

Szypowski was released from prison after seven years. He was not expelled from Poland because he had been granted citizenship a year before his arrest (he received it while spying for Russia). Although the Internal Security Agency (ABW) was tracking him, it agreed to issue him a Polish passport. Why? We do not know.

After his release, the former spy started a new law firm. He attends business conferences every few days. His favorite topics include the reconstruction of Ukraine, state tenders, and the FinTech industry. Friends and former colleagues describe him as a master of networking.

Stanisław Szypowski at a recent conference in Rotunda, photo: FRONTSTORY.PL

After publication of our piece, Szypowski continued to be a prominent figure. One of our readers recently spotted him at a conference on Ukraine’s path to the European Union.

Sviridov, Braun’s Buddy

Leonid Sviridov is one of the most recognizable people working for Russia in Poland. The 60-year-old journalist, who died this year in Moscow, worked as a correspondent for RIA-Novosti, an expert for Russia Today, and collaborated with Sputnik and Rossija Siewodnia.

Russian national Leonid Sviridov, operating under the guise of a journalist, was expelled from Poland in 2015 (the Ministry of Foreign Affairs revoked his accreditation at the request of the Internal Security Agency). Previously, in 2006, his accreditation was revoked by the Czech Republic. Unofficially, this was due to his links with the Russian services.

Leonid Sviridov and Leszek Miller, photo: Radek Pietruszka / PAP

In Poland, Swiridow built up a wide network of contacts and was a prominent social figure. On Facebook, he posted photos with Wojciech Jaruzelski, Lech Wałęsa, Leszek Miller, Radosław Sikorski, Marek Belka, and Andrzej Wajda. He organized a trip for journalists to Russia. Participants included Agnieszka Piwar, author at the Kremlin’s Sputnik; current editor-in-chief of Tygodnik NIE Agnieszka Wołk-Łaniewska; and historian Paweł Dybicz, deputy editor-in-chief of Przegląd.

From left: Grzegorz Braun, Leonid Swiridow, Agnieszka Piwar. Photo: Swiridow’s Facebook profile

In December 2018, three years after Swiridow’s expulsion, the Russian posted photos on Facebook with Grzegorz Braun against a backdrop of Christmas decorations. In a photo from January 2025, Sviridov appeared next to Tomasz Szmydt, a former judge who fled to Belarus and is suspected of spying for Belarus. The Russian died several days after the photo was published on X.

PHOTO /From left: Tomasz Trump, Oksana Rotszejn, Leonid Sviridov, Tomasz Szmydt. Photo: Szmydt’s profile on X

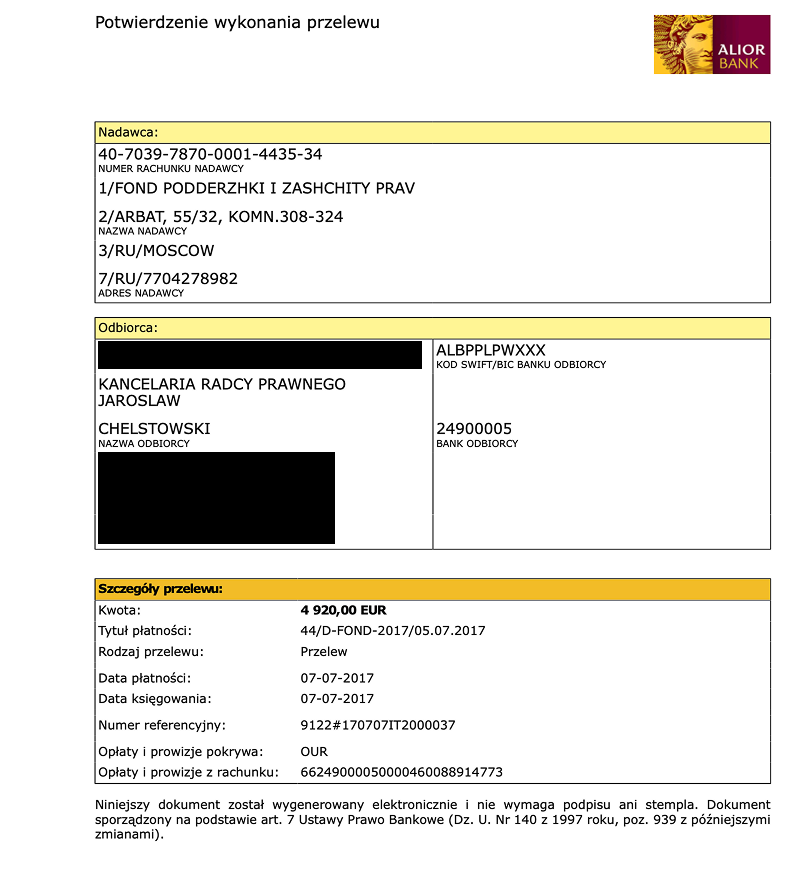

A Kremlin-managed fund paid for Sviridov’s court cases related to the revocation of his EU residence permit and his inclusion on the list of undesirable persons. The Russian was defended by the law firm of Jarosław Chełstowski, which received €9,840 (in two installments) for its services. Chełstowski claims that he did not know about the existence of Pravfond and does not remember who paid him for the case. We checked: in 2017, he sent Sviridov an email confirming receipt of a transfer from Pravfond with an address in Moscow.

Confirmation of transfer to Jarosław Chełstowski, Sviridov lawyer. Photo: Pravfond

Chełstowski emphasizes that, although he represented Swiridov, this does not mean that he approved of his activities. After Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022, he revoked his power of attorney.

Chełstowski values his privacy. In one of the few publicly available photos, he stands in front of the Russian embassy next to former Prime Minister Leszek Miller and Zofia Bąbczyńska-Jelonek, editor of the propaganda outlet Sputnik (the political idol of which is Vladimir Putin).

Jarosław Chełstowski (first from left), Zofia Bąbczyńska-Jelonek (first from right) and Leszek Miller (center). Photo: Wykop.pl

Medal for Defending Monuments

Established in 2015, the Social Committee for the Defense of War Victims’ Memorials (operating as the Kursk Association) cares for places and the memory of “heroes of liberation struggles and war victims,” as well as “developing contacts with veteran communities.”

It also undertakes unspecified activities to promote peace and cooperation between nations. Jerzy Tyc plays a leading role in the Association. He has been living in Russia for two years. The 58-year-old has links to pro-Russian activists (such as Mateusz Piskorski) and extensive contacts in Russia.

In 2016, Kursk activists in Soviet uniforms appeared on the propaganda channel Russia Today (RT) in a museum near Moscow, welcomed by the notorious Maria Zakharova, spokesperson for Putin’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

Jerzy Tyc (second from right) at a meeting with the Russian Foreign Ministry spokeswoman (first from left). Photo: RT

The Kursk Association cares for memorial sites associated with the Red Army. It was involved, among other things, in the case of the monument in Mikolin near Lewin Brzeski in 2018 and the idea of building a monument to Soviet sappers in Krakow a year later.

After Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, in December 2022, Tyc asked Pravfond for a grant for the “Poland – Map of Liberation” program, a virtual map of places dedicated to Red Army soldiers. We have not found any documents confirming that he received this money.

Tyc himself is often the main character in Kursk social media posts, appearing, among other places, in photos from Moscow, where, according to the caption, he took part in a Victory Day parade.

Jerzy Tyc representing the KURSK Association in the Moscow march of the so-called Immortal Regiment on Victory Day, Moscow, May 9, 2018.

Tyc received the Medal of Remembrance of the Defenders of the Fatherland from Russian Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu in 2020 for “the implementation of important public projects with a historical and patriotic orientation.”

From Pravfond documents: “Despite the positive effect of [Kursk’s] activities in the form of protecting monuments and memorial sites, [it] is the subject of criticism based on geopolitical prejudices.”

Mr. and Mrs. Tyc

It was because of these prejudices that Anna Tyc (formerly Zacharian), Jerzy’s wife, was forced to leave Poland. At least that is what the Tyc family believes – according to the ABW, the woman’s activities justified her detention and subsequent expulsion from Poland.

Anna Tyc was detained in May 2018, according to the ABW, because she “posed a threat to the security of the Republic of Poland.” During her detention, two identity documents were found on her: a Cypriot one in the name of Anastazja Zacharian, and a Russian one in the name of Anastazja Smirnowa.

On May 18, 2018, Zacharian-Tyc, also known as Smirnowa, was placed in a guarded detention center for foreigners. A few days later, she was taken to the border and left the territory of Poland.

Anna or Anastazja Tyc attempted to appeal the court’s decision, and Pravfond paid for her lawyers in 2020-2023 in cases concerning her detention and expulsion from Poland. She received almost €8,000 for domestic trials and €4,000 for representation before the European Court of Human Rights (she lost all cases). In addition, Pravfond transferred almost €10,000 to Tyc for legal assistance in the case of the vandalism of a Russian family’s gravestone.

The Polish Internal Security Agency (ABW) refused to give us the reason for Tyc’s expulsion – despite the passage of years, it remains classified. The Supreme Administrative Court’s justification for its ruling states that the activities of Jerzy Tyc and the Kursk Association were a side issue in the case.

The stated basis for the decision to expel Anna aka Anastazja Tyc was “findings concerning espionage activities.”

Emails From the Translator

Another Russian woman, Ekaterina Cywilska, also known as Katarzyna Cywilska, is associated with the Kursk Association.

In the photo: Jerzy Tyc and Ekaterina Cywilska Photo: Regnum

She came to Poland in 2013 to study and quickly infiltrated pro-Russian circles. She was expelled from Poland at exactly the same time as Anastazja Zacharian, and both women were associated with Jerzy Tyc and the Kursk Association. In 2014, Cywilska took part in a demonstration led by Jerzy Tyc outside the Ukrainian consulate. She was also a contact for Aleksander Usowski, as we described on VSQUARE.org. It was she who conducted casting calls for demonstrators and proposed candidates for pro-Russian rallies to Usowski.

Why was Cywilska expelled from Poland, just like Zacharian? The then-spokesman for the Minister-Coordinator for Special Services, Stanisław Żaryn, claimed that the arrests of the women were related to “neutralizing hybrid activities aimed at Polish national interests.”

There is no confirmation in Pravfond’s documents that Cywilska received money from the fund, but she did ask for reimbursement of legal fees.

Piskorski Sees the Third Reich

Despite his trial and charges against him, Mateusz Piskorski is active in public life in Poland. He runs an anti-Ukrainian YouTube channel (with almost 29,000 subscribers), establishes foundations, and, in December 2022, he took part in an “anti-fascist” online conference organized by the Moscow State Aviation Institute. Among the guests were pro-Russian journalists, activists, and politicians, including Maciej Wiśniowski, editor-in-chief of the Strajk.eu portal, and Piskorski himself. Konrad Rękas, leader of the now-defunct pro-Russian party Zmiana, was invited but did not attend.

The conference can still be viewed online. The opening speech was given by Serbian national Dragana Trifković, a well-known propagandist associated with the pro-Russian NewsFront and Putin’s services. In April of this year, Austria deported Trifković and banned her from entering the Schengen area.

In a video from the conference, Piskorski talks about his visits to Donetsk and says that “fascism reigns in Ukraine because dehumanization is taking place in Donbas” and that “contemporary Ukraine is an extension of the Third Reich project, which was taken over by the Anglo-Saxon world after the war.”

In theory, a Moscow university was responsible for organizing the event, but in reality it was a local government-owned company called the Creative Research Agency. It received 900,000 rubles from Pravfond for organizing the conference.

Media partners included the left-wing website Strajk.eu, known for its pro-Russian sympathies, and the IMHOclub website. The editor-in-chief of the former, Maciej Wiśniowski, as established by VSquare, traveled as an election observer in Central Africa and Madagascar, a journey funded by the European Center for Geopolitical Analysis, an association linked to Piskorski. IMHOclub is directly linked to Pravfond.

Russians Must Resort to Arms

In November 2018, three employees of IMHOclub, including its co-founder, were accused of acting against the sovereignty of Latvia.

Despite limited funding, IMHOclub continues its activities. Two of the portal’s creators fled Latvia: one lives in Belarus and writes for pro-government media, while the other is hiding in Russia.

The Polish author of the outlet IMHOclub was Mateusz Piskorski. Today, he claims that he did not receive any money for articles or appearances at Russian conferences. Wiśniowski from Strajk.eu makes a similar claim.

According to the indictment against Piskorski, before he was arrested for several years, he “participated in the activities of Russian civilian intelligence (…) directed against the Republic of Poland, in such a way that he held operational meetings in the Russian Federation and in Poland with designated persons officially representing Russian non-governmental organizations, but who were in fact collaborators of the above-mentioned intelligence services, as well as with an officer of one of these services, and received from these services (…) tasks to be carried out as part of the Russian Federation’s information war against Poland, and also initiated and developed task projects (…) and accepted money for their organization both in Poland and abroad.”

Piskorski’s trial is still ongoing in a Warsaw court.

Here You Go, Talk About Xenophobia

Pravfond covered the costs of participation and accommodation for many people during the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) conferences. These took place from 2013 to 2018 in Poland, Switzerland, Austria, and Italy.

Who? Among those who received the most funding were Wiktor Guszczin, head of the Latvian Baltic Center for Historical and Socio-Political Research; Aleksey Semyonov, head of the Estonian Legal Information Center for Human Rights; and Bilans Karlis, head of the Lithuanian Independent Human Rights Center. Pravfond also financed the participation of Paul Valery Engel, a Russian journalist and historian, head of the European Center for the Development of Democracy, in international conferences. Thanks to Pravfond’s funding, Engel participated in sessions of the Swiss Confederation, the UN, and the OSCE. Pravfond supported him with over €2,300.

In 2023, Pravfond financed trips for pro-Russian activists to a two-week conference, Warsaw Human Dimension 2023, organized by the OSCE in Poland’s capital. We found a list of the expected outcomes of the conference in the documents. They include “providing the OSCE structures with information on manifestations of xenophobia, aggressive nationalism, and neo-Nazism in EU countries and Ukraine based on the study ‘Xenophobia, minority rights, and radicalization in the OSCE area in 2020–2022.’”

Demonization Is Not Hard

In June 2023, Pravfond was sanctioned by the European Union, which describes it as a “unique structure of Russian soft power” working for Russia and supporting the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

The documents and emails we have seen demonstrate that Pravfond’s activities are like a giant film set: what happens there is made to look like it’s occurring organically, but the (supposedly) spontaneous demonstrations and apolitical conferences on human rights are, in fact, orchestrated.

Andrei Soldatov, a Russian investigative journalist and security expert, believes that conducting covert activities under the guise of legal aid makes sense from Russia’s point of view: “It is becoming increasingly difficult to provide cover for intelligence officers,” Soldatov explains. “Embassies are no longer as large as they used to be, and Russian centers are being closed in many countries. But if you create a flow, a stream of legal services provided to the Russian community, it will obviously be easier. This provides a new cover for spies.”

Normunds Mežviets, director of the Latvian State Security Service, confirms that his agency has been investigating PravFond for years: “We have noticed that people presenting themselves as independent experts, researchers, or employees of this fund are in fact officers of the Russian services.”

In its latest application to Pravfond, IMHOclub requested 9.6 million rubles (US$140,000) for activities in the Baltic states, Moldova, and Poland. The fund has so far agreed to transfer one-fifth of this amount. It is to be used to “counter the demonization of Russians in Europe” and “shape a loyal attitude of European citizens towards Russia.”

The Polish version of this investigation was published on FRONTSTORY.PL.

Subscribe to Goulash, our original VSquare newsletter that delivers the best investigative journalism from Central Europe straight to your inbox!

A Warsaw-based investigative and data journalist at VSquare and Frontstory.pl, Anastasiia Morozova previously collaborated with leading media outlets in Ukraine (Radio Free Europe, Slidstvo.info). She was shortlisted for the Grand Press Award (2022) and was a recipient of the Novinarska Cena 2022.

An investigative journalist at FRONTSTORY.PL, Daniel Flis previously was on the investigative team of OKO.press and Gazeta Wyborcza. OCCRP Research Fellowship Program recipient. Participant in international investigative projects of the Reporters Foundation.